|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| |

|

|

|

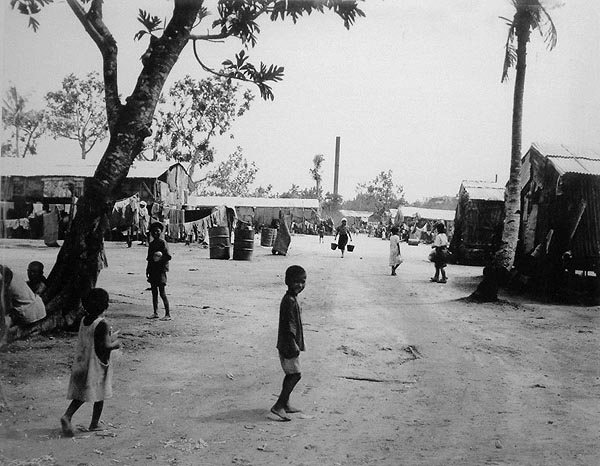

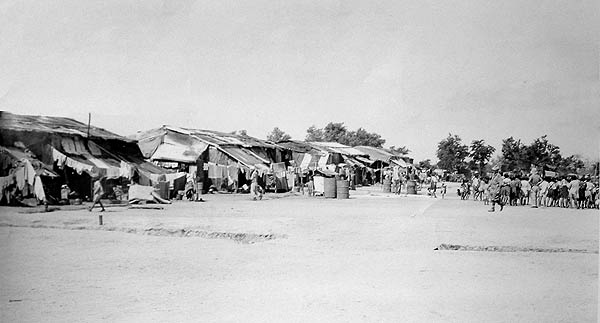

“After the Japanese surrender, the people here were concentrated into internment camps,” Noel says. “All the people who were captured were taken to Chalan Kanoa and Susupe. But the Chamorro and Carolinians were in one area. Japanese civilians, Okinawans, Koreans were in another; and then Japanese soldiers were in different areas, because they were being interrogated.”

|

||

|

|

||

“All the surviving local residents were moved down to what was really Camp Chalan Kanoa,” Scott elaborates. “It really wasn’t Camp Susupe (which was for Japanese nationals), but it was a separate camp that is where Chalan Kanoa village is now. "They were there from June or July of 1944, until I think July of 1946. That’s when the gates of Camp Susupe opened up: the Okinawans and the Japanese were repatriated, and the locals were pretty much allowed to go out. "But at that time pretty much everybody stayed in Chalan Kanoa, which became the major seat of population."

|

|

|

“I don’t remember much about it because I was so small,” Estella says. “But I remember that during the War the people were running from one place to another because the Japanese were chasing us. We were up in San Roque (Matansa). After the war, we went down to where the group of soldiers were, and they took us someplace where they had many military vehicles. “We climbed up on the cars and they took us to Susupe. And while we were waiting, my brother, he was so sick during the War that when my father and mother came out from the cave, they thought that he was with us, but when we came to the place where the group of soldiers were, my father found out that my brother was not with us. He was left behind, in the cave.

|

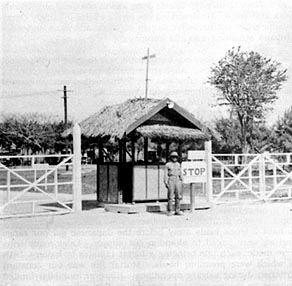

“When my father turned back, the soldiers went with him because they didn’t want him to go back alone. And that’s when they found him, crawling on the dead bodies. He’s older than I, but because he was so sick, he was crawling over dead bodies on the way down. There were very many bodies all over the place. “Then we went to Susupe. They made a tent for us to move into and that’s where we stayed until they finished renovating Chalan Kanoa. While we stayed there, the soldiers came and started trying to rape the families. If they saw that there was a lady, they would come at night and try to get her. That’s why they started fencing the place where the islanders were—they put a fence around it."

|

|

|

|

|

|

“When I was brought back to Saipan, I was put in the camp in Chalan Kanoa” Jesus recounts. “All the Chamorros on Saipan were put in that camp. At that time, it must have been in 1945, because that’s when I returned, there were still a lot of snipers who were still up in the hills. And we were being watched by Military Police in the Chalan Kanoa camp."

|

||

|

|

||

“The American soldiers brought us straight down to Susupe,” Rosa Castro recalls. “They would divide this camp, locals on this side and Japanese on the other side. The first day they got us there, we slept on the ground. There was a house but no floor, only the ground. We stayed about five or six months. They brought a truckload of shoes, maybe from the dead people. We had to make those shoes into zoris, slippers. “They brought a truckload of cans, empty cans, like one-gallon food cans. That was our pot, and our cup to drink water. And the wood we got from broken houses. They would bring truckloads of that wood for our firewood. For our food, they would bring a bagful of beans, and ham. The Americans now were supplying us with food."

|

|

|

“The life in camp is more or less a kind of hand-out,” Jesus explains. “You got food, and you just stayed in the camp. They brought in raw food, like rice and raw meat, and they cooked it themselves. In the camp, we were not allowed to go outside. The Military Police would keep us inside. "But mostly what we did there was clean the camp, cook the food, and help the American military—whatever they asked us to do to help them. Our life was good, because the Americans assisted us. We had food, water, and toilet. We were living in a house, not a tent. It was comfortable. We really had a good life then, when the Americans came in.”

|

“They started to open up the first school in the camp,” Noel adds. “And aside from getting their clothes and their food and everything, they wanted to teach the kids about their past, so they built a place to do their arts and crafts, to make a living out of it, and to do something worthwhile inside the internment camps." "They made crafts there, using the war materials: lanterns and containers made out of artillery shells. There are carvings from Carolinians depicting their place in Yap and in Palau. People made cloth, they made baskets, seed necklaces, cigarette boxes, bracelets from the war plane remnants. In this way, they made time worthwhile, doing more than just tending their wounds. "Aside from ‘one, two, three, apple,’ one thing the Chamorro will never forget is SPAM. Corned beef and SPAM."

|

|

|

|

|

|

“We left there after maybe two years,” Estella says. “They moved the tents, and then we started going away from that place. I went to school in Chalan Kanoa Elementary School and at that time, it was called Commander Findley School. Then maybe about 1947 we moved to As Lito, close to the airport. We stayed together with my mom. My brother Pete was working at the Telephone Company, in Tuturan—San Vicente, they used to call that place Tuturan. And that’s where my brother was working. "We used to ride on the bus to school. There was only one bus at that time, and it was a truck, and they put a house on it so that when it rained we wouldn’t get wet. And the driver during that time was Rafael Mafnas. That was our school bus driver. So only one bus, taking all of us to Chalan Kanoa Elementary School—that’s Findley school."

|

||

|

|

||

“We were in the camps almost a year,” Jesus says, “but I think after about 6 months the gate was opened. When the gate was opened, that meant we were free. We could go out and find our own place, and a lot of people started going out and looking for jobs. That’s about the time, 1948, when we came here to Tanapag.” “They said they were going to move us,” Rosa recalls. “The older men would go around Chalan Kanoa because Chalan Kanoa is empty, and they would select a house. And then we, the people of Tanapag, our camp was just south of the cemetery at Chalan Kanoa, the Texas road. The people of Tanapag, when we got out of the camp, we moved down to that place and lived there. In about 1946, it was opened."

|

|

|

“In the very late 1940s, into the early 1950s, that’s when we started building the villages that now exist,” Scott points out. “San Antonio was an old military concentration building. San Roque and San Vincente were established then. Oleai was where they kept the Koreans, in the Korean internment camp. "So all of the villages that everybody now thinks are the traditional villages (other than Garapan and Tanapag) are all post-war villages that never existed before. "The Tanapag people were the only people who moved back to their original village. As soon as they were allowed to, they moved back."

|

|

|

|

|

| "The Tanapag people went up to Commander Mortenson, up at Navy Hill, and asked if we could move back to Tanapag," Rosa says. "Commander Mortenson said yes, but they would first check for materials of the war (unexploded ordnance) and move anything like that out of the village. So we moved back here in 1947. "When we settled back here, there were four houses. Four families built four houses after the war. There had been some destruction in the village. And there was no water or electricity. Our light was candles. My family dug a well in the ground and got water from the ground. Then still others were coming back, and we filled up the village again. "There were houses here at Tanapag," Jesus recalls, "but they were broken down by the war. Now at that time, we rebuilt houses for our own." "There was only one utt," Rosa continues, "just the talaabwoch falawal. There were a lot of canoes because we’re the only ones who make canoes, sailing canoes. We cut breadfruit trees and shape out the canoes, sailing outriggers for the inside lagoon."

|

||

|

|

||

|

"There was a big difference when the Americans arrived. It was cheap to buy things. In the Japanese time, there were no rations. If you work, you eat. If you don’t work, you don’t eat, unless you eat the plants around the house. "Haikyu is a Japanese word for rationing. In those days during the Navy time, people were given rations: bags of beans, ham, rice, bread, coffee, salad oil, sugar; people didn’t have to eat sugar cane anymore. "The drinking water came from the cistern. We caught rain water for drinking from the roofing tin. For showers, we used the well. For washing we used the well. But for drinking, we caught it from the rain."

|

| |

|

"This side of the village was still Tanapag but there was a fence that went all the way down to the wetland. We could not go in there because there was a guard. Only the Navy people and their families."

Along with this great transformation, half the village of Tanapag was now fenced off for use by the NTTU, the Naval Technical Training Unit.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanapag Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||