|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| |

|

|

|

“Things really changed during the Trust Territory time,” Noel says. Saipan became the capital of the Trust Territory of the Pacific, with delegates for the different entities coming to Saipan to participate in the governance of the TTPI (Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands). Noel adds, “There were a lot of people from Micronesia working here because of the government.” "Being part of the Trust Territory," Juan says, "I realized that the Carolinian members of the community would still really travel back and forth to see their relatives in the Caroline Islands, or the Caroline Islanders would come to Saipan to visit their relatives here, so it became much easier to visit between those places."

|

||

|

|

||

“During the Trust Territory time, the local people were still discriminated against in terms of salary," Noel remarks. "If there was a State-sider working the same job, that person would be getting more money than the local person. If I worked for eighty cents an hour, the State-siders were making more. They got two dollars an hour. You know, that’s not right. But that was then." “Goods and commodities were cheap, though. Twenty-five cents would be enough for me for the whole day. Five cents to get a really good meal. Everything was so cheap. But there were not a lot of ways to make money other than having a store. "One job we did is that we collected copper and brass, scrap metals. In the boonies we’d find empty shells, and we’d sell them. At one point, there was an infestation of millions of rats, devastating the crops. So that's one time the Municipal Government said that we could bring in dead rats, and they would count by the tail, and pay for that. So we did that. And they even paid for snails by the pound, gigantic land snails. "But a lot people were dependent on subsistence living: they had their own plantations and they ate whatever they produced by the earth and the ocean."

|

|

|

"During that time, discussion was taking place in the Congress of Micronesia," Juan states, "about the political status of the Micronesian Islands. I was not as informed about the intention of the United States back then, as to why they wanted to break up the Trust Territory. "But thinking about whether or not we should have a political affiliation with the United States, made me feel that I needed to become more informed—go to college and start reading about all these issues."

|

"Growing up, I guess I was pretty much, I’m going to say, brainwashed," says Noel. "Looking at the TT time, I guess the people decided that they saw a bright future under the U.S. flag because we saw such changes during the TT time. But looking back, I realize that the reason we had so much change is because the capital of the Trust Territory was here. "And the rest of the islands were not really so developed. And then the people decided to be independent from the rest of the Trust Territory, and become part of the U.S. And I said, ‘I think we can do that.’ We wanted to move forward."

|

|

|

|

|

|

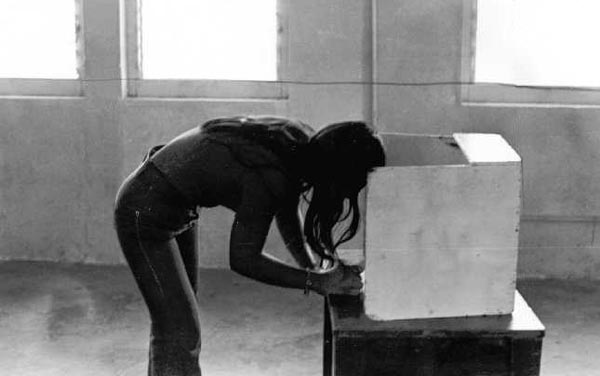

"When the formal democratic process was introduced on the island, with the first election," Juan says, "it just broke up the entire community. Before the formal democratic process—meaning people electing commissioners as well as electing the representatives for the District Legislature—people would go and help other members of the community if they were going to build a house. "If you were building a house and someone in the community has a two-by-four, they would bring the two-by-four and give it to you. If they had ten nails, they'd bring the ten nails; and everybody would just chip in. So it was much, much easier to build or achieve what you wanted to do, because the community would all come in and help. If you had a party, all the community would be there. If it was a wedding, everybody would be there."

|

||

|

|

||

"Then when politics came, it divided the community. Back then they had what they called the Popular Party and the Territorial Party. And so from that time on, that process split families, and I’ll use my family as an example. My mom and my dad joined the Popular Party, and all my mom’s brothers and cousins and all their relatives joined the Territorial Party, and of course there was a lot of propaganda from each, and those are the propaganda that forced people to choose to become members of certain political parties. "But I realized that the community, the closely knit community, started breaking up. Members of the Popular Party would help other members, like when they were building a home. They would all just bring whatever, just like before; it’s just that now there would be a division, along the party lines. Territorial members will help only Territorial members. If a Territorial member had a party, only members of the Territorial Party would go and help."

|

. |

|

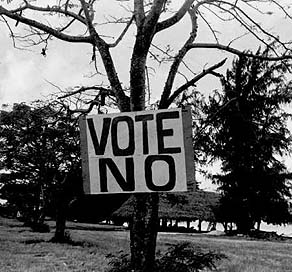

"The Popular Party is now the Democratic Party and the Territorial Party is now the Republican Party. The Territorial Party wanted to keep the Trust Territory together. And the Democratic Party—the Popular Party—wanted to join with Guam. Guam voted against the idea of joining with the rest of the Marianas. "Well, my own interpretation from my own experiences going to school on Guam right after high school, is that they felt that we were an underclass. They felt that they were much higher than we were. Back then, on Guam the minimum wages were already about $1.00, $1.10 an hour, while here, in all the Trust Territory, it was only 33¢ an hour. So that’s one of the reasons why it was very hard to go to Guam and work. It was very strict."

|

"I went to go to school on Guam for about a semester. And I couldn’t take their roughness. By 1968, it was getting easier to go to Guam for school, and they had the Guam Community College. It wasn’t the University of Guam back then. And so most of the graduates from the high schools among the Micronesian Islands were all flocking to Guam to go to Guam Community College. "I went to Guam Trade School, and it was hard. People from Guam wouldn’t let Trust Territory students use the bathroom. It was very rough. Not only was it hard to go to school without family nearby, but to have another problem of having to wait until everybody goes to class before you can go to bathroom…. I said ‘No, that’s not for me’."

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Twice in the sixties we asked Guam to unify with us," Noel points out. "And ninety percent, the majority of people here, said ‘Let’s unify with Guam.’ Ninety percent in Guam said ‘No.’ The reason is that, when the Japanese invaded Guam, they used some of our own local people to interpret for them. We were already a Japanese colony. And so the Guam people were accusing us of being on the side of the Japanese.” "Actually, we were forced. The people from here said, ‘I’m just interpreting.’ Then the Japanese would say, ‘You slap him,’ and the guy would say, ‘I don’t want to slap him.’ ‘If you don’t, I’ll kill you.’ So, you know, the interpreter just closes his eyes and slaps the Guamanian, for example. What can he do? That’s why that feeling between Guam and Saipan from that incident is still strong. Some of our people that were involved have not stepped on Guam up to this point in time. They were hated. Their names were hated because of their role in the War. So Guam decided no."

|

||

|

|

||

"Now that we have become a Commonwealth with more privileges, Guam wants to be with us. And I say no. They realize that we own the rest of the islands up north, and that we are combining all the resources and the minerals and everything that’s untapped. Now companies are coming here to tap the volcano for the black ore that the volcano emits. "There’s a mineral in it called pozzolan, and there are only two other places in the world, Italy and Greece, and then Pagan, that produce this high quality volcanic ash. It’s a mineral that is excellent for building blocks, structures, paving the airport. And now companies are using it for that. And now the Americans also realize that we have a lot of manganese, and titanium alloy in the ocean."

|

|

|

"So now Guam realizes that they want to be with us, but I say, ‘Sorry, dude. You know, we asked you twice and…’ Just because of that incident. Now when people from Guam tell me about the World War II story, I say, ‘Well, don’t you remember back on March 15, 1695?’ They just look at me and go, ‘What about it?’ I say, ‘When the Spanish took you guys to slaughter us at Agingan Point?’ "They go 'Huh?' But it's the same thing as the Japanese taking us to interpret. So I say, ‘Hey, we’re even.’ And they just keep quiet and wonder, ‘What is hey talking about?’ And the one American scholar goes, ‘Ahhh, now you see. When the Chamorros from Guam allied with the Spanish to slaughter the Chamorro from Saipan, Tinian and Rota...’ They know. And the Guamanians say, ‘I didn’t know that'."

|

|

|

|

|

"Back then I got involved, but not as intensively as I would today," Juan remarks, "because back then we still had this local attitude of 'Yes, sir! Yes, sir!' And there was less than a handful of people back then who managed to learn the 'No, sir.' So it was hard to be involved. I was a teacher back then. The culture was such that when I went amongst the elders, although I knew that I was informed in some way, I could not just share my thoughts without being asked.

|

||

|

|

||

"So all of these traditions played a role. You know, I could be in a meeting where the elders back then were discussing the issue, and I was also being an adult part of the society, being a teacher, but yet I couldn’t share my thoughts, because my uncles and my aunties were there. It was hard. “TT time and the Democratic process had an influence on the culture in terms of our relationship with the elders. And it’s good and bad. It’s bad because it is the American system that breaks the tightly knit community. It breaks it apart. It’s good for us younger generation, because it taught us to be independent and speak our minds."

|

|

|

In the end, the Northern Mariana Islands became a Commonwealth freely associated with the United States. "I think that becoming a Commonwealth was the best thing for this island,” Rosa Tenorio says, “because we do govern ourselves. We make our own laws by the supervision of the Federal government, and I think that the people should have the right to run their country."

|

|

|

|

While changes in governance brought greater autonomy to the Northern Mariana Islands, and Americanization brought great cultural changes and changes in lifestyle, a legacy of the war and postwar period would seep up from the ground to grip the community of Tanapag. On the next page, we will learn about the legacy of contamination in the village.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanapag Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||