|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

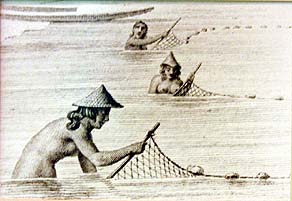

Fishing off the edge of the reef near the Inarajan cemetery.

|

|

|

"When you go further into the bay," Joe continues, "seasonally you have mackerel runs, we call it atulai, and with purseine nets you go and circle around the bay." Fishing the seasonal mackerel run is the activity for which Inarajan is named, and it is well remembered by many residents. Bill explains, “There is actually a meaning to the word Inarajan. ‘Ina’ means to 'shine forth' or to 'give light.' There is a season for the mackerel fish to come into the bay, and the villagers would go there late at night with torches. People would come down from the hills with their torches and they would use the lights so that it would invite the fish into the bay area. "Then early in the mornings, people would get up and stretch out their nets and catch the fish at that point. According to the stories that were handed down to us, 'Inarajan' was given as being something that is going to shine or to give light. And so that’s how they actually named the place."

|

||

|

|

||

|

"All the villagers will come out and pull the net in," Joe describes, explaining how it is done today. "You have divers to make sure that the net doesn’t get tangled underneath on the rocks, you have boat people that make sure that the net is pulled in also by the boats, and then you have the people that pull at the two sides of the net, they pull the net in. The bottom of the bay here, there’s a channel that is more silt or sand, and that’s where they pull the net, through that area. Communication between the divers and the pullers is vital to get as much fish from the school as they can. "They eventually pull the whole net into the beach, but when they see that there’s a lot in the net, then they have to scoop them out, because it will eventually tear the net when you start pulling it in. So they would scoop them up a little at a time so it will be much lighter for everybody to pull that school in. And you get maybe three, four boatloads of fish."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"I remember, there were people who knew how to swim." Bill recalls how it was done in his childhood, "Most of the men, 99% of men, were really courageous getting all of that net out into the bay. They swam out, no canoes, and they’d take all the nets out. I don’t know how they’d tie them together, but then the pulling would begin. That’s when the women and the children would come together to pull the net in, and boy I’ll tell you, the whole pile of fish would come right onto the black sand." Tan Floren recalls an even earlier time: "I think they had canoes to put the net, to close it, because you cannot close it, it’s too deep, so they have to use canoes to put that net down to catch the mackerel. Some of them would close that and put the net, and they just keep pushing that in a little until it’s close there."

|

||

|

|

||

|

"Then the sharing would take place," Bill continues. "Commercializing the catch was unheard of. As a family you gathered there and you waited your turn to get your share. It was all divided by the number of families; even if one was not there, somebody was supposed to be responsible to take care so that fish got to the family. There is no such thing that you didn’t get your share because you didn’t go there. The thing about sharing is that the one who actually does the most catching usually ends up with the least, because that was the person was responsible. You know, 'Take it, please take it' and before you know it, you don’t have much to take home! I remember going with somebody and I just tagged along and got quite a bit of fish going home. I thought that was a beautiful part of the culture."

|

|

|

|

"I remember when I was a little child, down where Bear Rock is, that used to be a big place for catching mackerel, atulai. I was only 5 years old," Therese recalls, "and we weren’t allowed to hold the net, but we were allowed to go and pick a fish. Any child, as long as they could walk and hold a fish, that was theirs. "Nowadays they sell the fish for a living, but when I was a child I remember anybody who could walk could go down, and they were given fish. The whole community, even the sick, anybody who was elderly, they were given their portion of fish. So it was distributed throughout the village. Nobody used it for sale. It was common knowledge that when you bring in fish, you shared with everybody, and every child that went down onto the shore got a fish, and whatever fish you got that was yours, you brought it home and your mom would cook it."

|

|

"And you know, when they catch a lot," Tan Floren adds, "they give to the people, house to house. They give first to the priest, and the sisters, and then the remainder they put house to house. Either ten or five. If they have more to give, they give twenty. So if you help that, pull in, they give us more. My cousin and I would go in the deep water, kept pulling that net in, so we’d get more. And then we’d share with the family. It was mackerel, and others like skipjack. And some days they would catch that aguas (baby mullet), to make the kélaguen. Even the mackerel, you can make kélaguen out of it."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

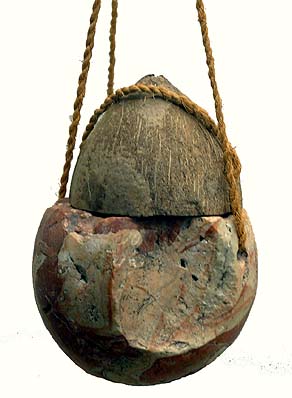

"We can still see today techniques that the Spanish described," Anne says, "so we assume it’s a continuity from the past: net throwing and certain lures. There’s one lure called the acho’. It’s a heavy stone, and they would cap it with a coconut husk and then fill it with grated or mashed coconut and drop it down off of their canoes. Then they would pull the coconut up with a rope to lure the fish to the surface and then kind of scoop the fish up.” Larry adds that the fisherman worked at this for several days, starting the lure in about 60 feet of water and each day feeding the fish a few feet closer to the surface, until he was able to scoop them up. Apparently the practice continues today in the Marianas. “A friend of mine has one of these lures” Anne says, and I asked him ‘Well, where’d you get yours?’ and he said ‘A fisherman in Rota, he has so many so he just gave me one’.”

|

|

Fishing from boats today is not so common. Earl states, "I used to go out on the boats and fish, but it’s been a long time now. Out there on a calm day, it’s good, the best time. Some areas, you can see the reef, but then you go further out and that’s when it starts to drop. It goes down like a slope. You can catch bottom fish, skipjack, you catch those lililok, the red snapper. As long as you’re catching, it’s good. Bottom fishing, you just drop your line down, and wait for them to nibble, and when they pull, you reel. Use squid for bait, or mackerel. You go like 600, 800 feet, or sometimes 15-20 feet. It depends what area you are in."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

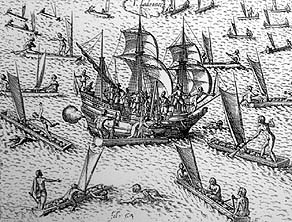

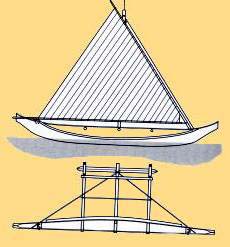

“It’s ironic," Anne says, regarding the loss of boat and canoe culture, "because when the Spanish first come, all their accounts go on and on about the canoes and how fast they were, how well designed and so forth. Of course these are all Spanish navigators writing, so they’re all impressed. But when the wars break out, the Spanish see those canoes as the most threatening weapon the Chamorros have, because when they see the soldiers coming, the Chamorros are constantly jumping on their canoes and taking off to other islands. So what the Spanish once thought was the greatest thing in the world, they soon started to view as the worst. Consequently they burned canoes whenever they had an opportunity.

|

|

“Like the latte stones,the canoes end with the coming of San Vitores. I think this is partly because building canoes, like the lattes, requires a lot of time, a lot of manpower, and a lot of resources from the clan. Once you’re in a period of war, no one has that luxury. What was once a part of everyday life, now is pushed to the side because you don’t have the resources. "You can kill a canoe culture in a very short period of time once, in one generation, you get rid of all of the canoes. Then with introduced diseases, so many people died that simply to have the amount of people necessary to build a canoe is taken away from you. Just the sheer physical numbers of people and the resources, in a short period of time, was lost. Add to that the loss of navigational knowledge due to the deaths of key people, plus the loss of the guma' uritao where knowledge was transmitted, and you have a real crisis in navigation."

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chamorro terminology regarding fish and fishing is presented in this chapter's Language page. Our next chapter focuses on the Land.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Inarajan Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||