| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

|

|

Google Maps 3-D image of Hiva Oa, in the Marquesas.

|

|

|

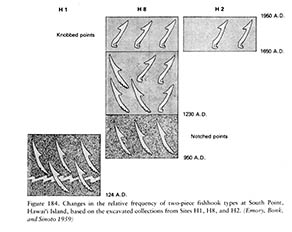

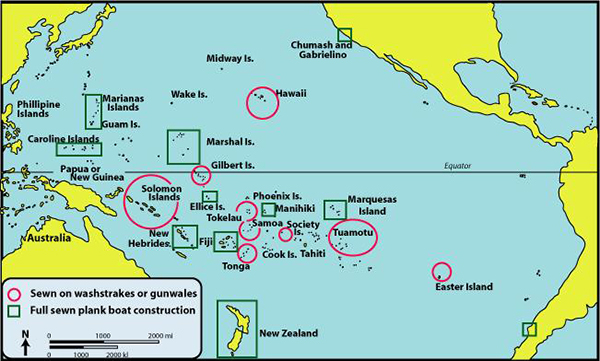

“As far as the human history of Ko‘olau and of the Hawaiian islands,” Kalani begins, “it’s still very much a matter of debate as to when the first ancestral Hawaiians arrived. Archeologists have determined that the first settlers were probably from the Marquesas Islands—from the southern Marquesas islands, Hiva ‘Oa. When you look at the dialects in the Marquesas, Hawaiian looks much more like Hiva ‘Oa than does Nuku Hivan. So being a student of Sam Elbert’s, I looked into his research and I was able to identify thirty-plus words that are strictly Hawaiian and Southern Marquesan only. Hiva Oan—only. “I think that in addition to all the archeological evidence—the artifacts, the fish hooks and tattooing implements and what not—you’d have to say the first comers to Hawai‘i were from the Marquesas. And then inthe 1000s, 1100s and up to the 1300s, huge Tahitian input, and they take over. So the language today is more Tahitian than Marquesan. And then of course with all of these ancestral names it’s very clear that we are Tahitian derived. “But what’s interesting now with Hawaiians and Māoris making contact as never before, they can claim the same ancestors out of Tahiti. And we know exactly where we branched off and which ancestors we share, and so the Māori always say they feel closest to the Hawaiians than any of the other Polynesian groups. It’s a very strong, developing relationship now with them. Very strong. “In terms of the most successful voyagers in history, setting out from Southeast Asia, to about three thousand B.C. more or less. And then of course making their way, migrating along the northern parts of Melanesia out to Fiji, Fiji to Tonga and Tonga to Sāmoa. Tonga and Sāmoa to the Marquesas later to Tahiti, and then later to Hawai‘i. So the question is when was Hawai‘i first settled and I’m inclined to very much tend to go with the dates that were talked about earlier, before the revision came along, and the date is that Hawai‘i was certainly colonized by 500-700 A.D. “But other dates we’re getting from Lāhaina, 45 A.D. from Moku‘ula. And then from O‘ahu, one site in Kahana Valley and another site in Kahuku [both in Ko‘olauloa], the carbon-dated material done by Bishop Museum archaeologists—both of which were B.C. dates.” One was 130 BC, the other 165 BC. “But those have been dispelled and disregarded by Bishop Museum, ‘well you need much more evidence than just one or two dates.’ Bellows Field site in Waimānalo used to be one of the oldest too, A.D. 500-600.” “Most researchers still accept an A.D. 300s-600s range for the initial occupation of the Bellows area, while realizing that most site areas date from the A.D. 900s or later,” Ross Cordy writes.

Archaeologist Ross Cordy, in his 2002 booklet The Rise and Fall of the O‘ahu Kingdom, writes that “A 1970s model of Hawaiian cultural changes suggested that permanent settlement was first established on windward O‘ahu in the Ko‘olauloa and Ko‘oalupoko Districts, and this concept has been widely accepted. There, high rainfall and perennial streams supplied a consistent source of water for agriculture. Drought and crop losses were unlikely to occur, in contrast to the leeward side. The windward areas also had easy access to marine resources. Early settlement was suggested to have taken place about the A.D. 300s-600s.” “There are all these voyaging traditions between Tahiti—the homeland—and Hawai‘i that are part of Kāne‘ohe bay,” Dennis reminds us. “It seems odd—Kāne‘ohe Bay being on the opposite side of O‘ahu from Tahiti—that that would be such a place of voyaging traditions. The only reason I could think of was that it’s all relatively well protected, and there’s a lagoon in there. So if you were voyaging, you could bring the canoes in. Maybe also because it’s on the windward side, and if you were sailing downwind from the East, that might be a place that you would anchor.” “I would assume that there were people already here because the voyaging chiefs actually came and that might be a second wave of migration on the early class. Before that time there were settlers from Polynesia here, but they didn’t have that kind of ali‘i status. That culture came later with all the kapu and this and that. My sense is that based on what I read in the Polynesian Family System in Ka‘ū by Mary Kawena Pukui. She described more of an ‘ohana—family—kind of culture in islands that preceded the ali‘i culture. And it was based on the elders in the family being in charge. The ‘ohana would be attached to certain places, and so I would imagine that there were ‘ohana in the Kāne‘ohe Bay area before the voyaging chiefs came.” Ross Cordy agrees: “Most researchers assume that during this early period, political organization would have been in small polities with the Ancestral Polynesian primogeniture ranking and chiefly system, but with minimal hierarchical organization....Number of small polities are expected to have existed in windward Ko‘olauloa and Ko‘olaupoko....I believe the polities would have been smaller in size, judging from patterns of simple-ranked societies in Polynesia at European contact. Lands within the community would have been held by nonunilineal kin groups, and the territories are suggested to have extended inland up the valleys.” “There’s a movement now,” Kalani continues, “and it’s gaining a lot of strength, claiming that the earlier dates were inaccurate and need to be disregarded. However not everyone says that’s true. No, those are still some reliable dates. “Archaeologists from New Zealand and also Chilean archaeologists have been digging on Mocha island off the coast of Chile. They have discovered not just Polynesian artifacts but Polynesian skeletons, skeletal material, greenstone (pounamu). How do you account for that? Who would take pounamu—New Zealand jade—all the way there? They had to be Polynesians.

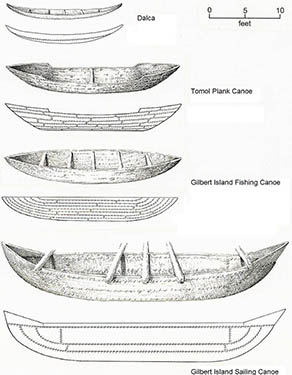

“Sure enough, we know that the Polynesians introduced the Southeast Asian chicken to Chile before the Spanish brought the chicken in. And in exchange, the Polynesians took back to Polynesia the sweet potato, which is of highland Andean and Peruvian origin. And not only that, we borrowed the name as well: Kumar in Mapuché, on the language map it became Kumara. Kumala, ‘uala in Hawaiian. Same name, same product. “So the migration and settlement dates, they remain controversial. Kathryn Klar, U.C. Berkeley linguist, was researching the Chumash people in the Santa Barbara area. Catherine was a specialist in the Chumash language and came across these canoe-related terms that were not typically California Indian! She said, what in the world?! Why would the Chumash be calling a canoe tomolo‘o whereas other surrounding California Indian groups have very different names.

“So she’s trying to reckon this odd term and couldn’t figure out where this term might have come from until she got a Hawaiian dictionary and worked out that the ancestral term for a built-up plank canoe, was tumulā‘au in ancient Hawaiian, old Hawaiian, tumulā‘au became, in their language, tomolo‘o. They love o’s, so tomolo‘o, shortened to tomolo and then tomol. And then not only the name for the plank canoe, but for fish hooks and for different kinds of canoes too, the one-man canoe. “And with noted California archaeologist Terry Jones doing lots of archaeology there in the Santa Barbara islands and the Santa Barbara coastal areas, they have concluded after many years that they have definitely, without any mistakes, uncovered Hawaiian and Polynesian artifacts. And he was called dirty names and what not, poor guy. “The dates Terry Jones got for these fish hooks was A.D. 700. So you figure they have to have been ancestral Hawaiians, they wouldn’t have been Māori or Tahitians, because they were really the closest to the new world, to California. And you got the word, and other words that also derive from Hawaiian, taken into Chumash and Gabrelliano as well so what can you conclude? Hawaiian, and I showed pictures of the fish hooks to noted Pacific archaeologist Bob Suggs and he said ‘Yeah, those look very Hawaiian and these look very Marquesan.’ and so what are you going to do!”

|

|

|||||||

|

Voyaging is what brought Polynesians to the Hawaiian Islands, but once here, they imprinted upon the landscape the stories of their ancestors and their journeys, and stories of the gods. These contribute to the legendary setting of He‘eia.

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

||||

Copyright 2019 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||