|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

| |

|

|

|

|

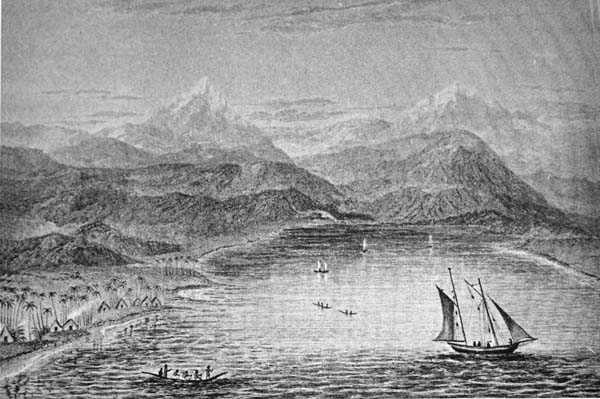

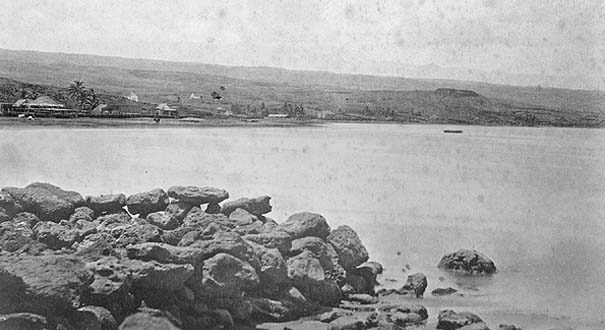

“Kawaihae Bay in the 1820s was the only trading port along the northwest coast of Hawai‘i Island,” Chiogioji & Hammatt write. “The village at Kawaihae not only served the sandalwood trade, it served as a trading center for four Waimea villages….The surplus taro and vegetables raised at these villages were brought for trade to the coast of Kawaihae” (Chiogioji & Hammatt 1997: 17). As the Hawaiian Islands were roped into the expanding cash economy, Kawaihae experienced the new economic forces that shaped the islands in the 19th century. These included the trade in Hawai‘i's sandalwood that Western merchants were pursuing in China, and the hunting of whales in the Pacific, as well as off Hawai‘i's shores.

|

||

|

|

||

“The Hawaiian Islands began exporting sandalwood to the Orient shortly after 1800," Chiogioji & Hammatt continue, "and the commerce flourished until the supply dwindled in the mid-1830s. Trade in sandalwood was the strict monopoly of the ali‘i beginning with Kamehameha. "After Kamehameha’s death in 1819, Liholiho (Kamehameha II) allowed his chiefs to share in the sandalwood trade, resulting in an unrestrained demand on the stocks of the wood and upon the commoners who did the harvesting. "At Kawaihae, John Young supervised royal warehouses that were the central depository for the wood brought in from the surrounding district” (Chiogioji & Hammatt 1997: 17).

|

|

|

“Before daylight on the 22nd," William Ellis wrote in 1824, "we were roused by vast multitudes of people passing through the district from Waimea with sandal-wood, which had been cut in the adjacent mountains for Karaimoku, by the people of Waimea, and which the people of Kohala, as far as the north point, had been ordered to bring down to his storehouse on the beach, for purpose of its being shipped to Oahu. "There were between two and three thousand men, carrying each from one to six pieces of sandal wood, according to their size and weight. It was generally tied on their backs by bands made of ti leaves, passed over the shoulders and under the arms, and fastened across their breast. When they had deposited the wood at the storehouse, they departed to their respective homes” (Ellis 1969: 397).

|

|

|

|

|

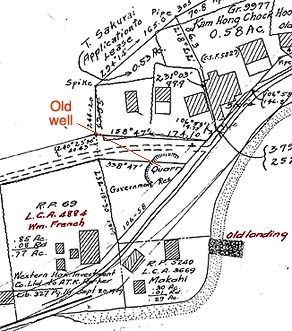

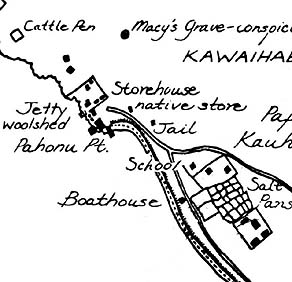

“Mauka was forest,” Papa says, “and the forest used to be lower. And Isaac Davis said, when the sandalwood was in operation, the people used to come from mauka, pass right along the house where he was, and you could hear them talking, walking, all with sandalwood on their backs. They were bringing it down right in the front over where Doi Store was. They had a pier over there, and that’s where they used to send it out. “If you look where that water well was, straight in front of that, they had a pier over there during the sandalwood trade, with warehouses and stuff like that. It used to be a dry dock. After that had been dry dock, it was pier. One pier there, one pier this side, then later two, three and four. But this was a major sandalwood port.” “By the end of the 1820s the stands of sandalwood in northwest Hawai‘i were exhausted," Chiogioji & Hammatt point out. "However, new enterprises were emerging to fill the void and activity at Kawaihae Bay would continue apace” (Chiogioji & Hammatt 1997: 17).

|

||

| |

||

“American William French set up business in Waimea and Kawaihae in 1835," Chiogioji & Hammatt state, "building an export company shipping hides and tallow, along with other products, out of Kawaihae. “At Kawaihae village, French opened a second store on land he had acquired in 1838 from Governor Kuakini on condition that he build a pier for landing canoes at the bay…. "His store was apparently the first commercial building in the village. It was the only one there in 1840 when a visitor found Kawaihae ‘barren and almost destitute of inhabitants….A well-built store and a few houses constituted the only appearance of a town. There was no vegetation to be seen’” (Chiogioji & Hammatt 1997: 20).

|

|

|

“Foreign trade that, by 1849, linked a demand for potatoes in California with new-found riches in Waimea, had been developing throughout the century” Chiogioji & Hammatt write, commenting on the impact of the California Gold Rush. “Lyons announced a startling reversal in the fortunes of Waimea and Kohala”:

|

|

|

|

|

The growth of the Pacific whaling industry spurred on the development of the Kawaihae-Waimea area. Billy remarks, “The major concentration of whales was along that Kawaihae coast, and off Puako. And of course Lahaina Roads on Maui and all that area. That’s where the whales were plentiful. “Sweet potato was one of the main staples for the whalers when they came in. In the lowlands of Kawaihae Uka, and below Waimea, lower Lalamilo and throughout that area, you see a lot of stone walls. There was a lot of planting, because they knew how to get the water from the streams, and in those lowlands they raised quite a lot of crop."

|

||

|

|

||

“They used to say ‘damn fool Kawaihae,’" Billy says, "presumably because we think anybody who lives there is stupid because it’s so darn hot and windy. But no, the reason for why they say ‘damn fool’ is when the natives would bring down the bags of sweet potatoes and the whalers would buy that, they’d say, 'Jam it full! Jam it full!' And the Hawaiian would say “Damfool, damfool,” you know. “Jam it full.” "Kamelakakelipio was my wife’s mother, she was almost pure Hawaiian, and when we’d say ‘Damn fool Kawaihae,’ she’d jump all over us and she’d say ‘No, no, no! It’s jam full – jam full – jam full.’"

|

|

|

"1859 was the year the whaling industry reached its peak and prices for whale oil collapsed five years later" Chiogioji & Hammatt state. "Since the 1840s, the Hawaiian economy had been dependent primarily on supplying whale ships during their long layovers in the islands. As the number of arriving ships dwindled during the 1860s, cattle ranchers and entrepreneurs of Waimea who could not find new markets were forced out of business. Among the survivors was the Parker Ranch which would play an ever increasing role in the life of Kawaihae through subsequent decades. "However, these troubles were a few years off in 1860 when a consortium of the Hawaiian government and private investors formed the Hawaiian Steam and General Inter-Island Navigation Company to initiate regularly scheduled steamship transportation between the islands" (Chiogioji & Hammatt 1997: 27).

|

|

|

|

“The shift to the capital economy is another ache in my heart,” Hannah says, “similar to the ache that came with the overthrow of the Monarchy. It stood us away from the self-reliance of the traditional surplus economy where you grew enough to generate a surplus, but were not working for the purpose of export or cash exchange. With that change, you get a really different kind of thinking occurring.”

|

||

|

|

||

The increasing importance of the cattle industry, and the role of Kawaihae as the port serving Waimea and the northwestern portion of Hawai‘i Island both have enduring impacts. We will hear about these and other forces of change in the Memories chapter.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kawaihae Home | Map Library | Site Map | Hawaiian Islands Home | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2006 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||