|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

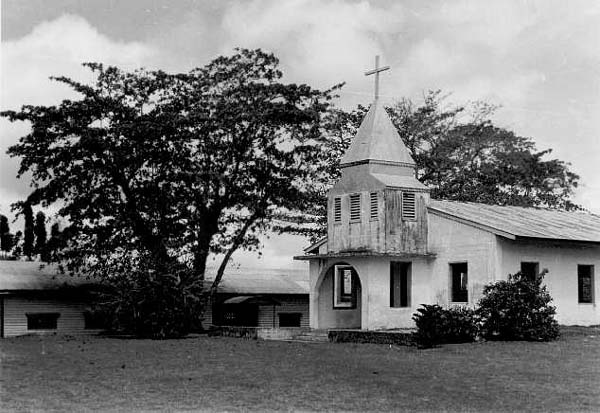

"The Spaniards came and claimed the area for Spain, and started Catholicism," Kathy tells us. "But they didn’t actually do anything here. There were missionaries from Guam—one that comes to mind is Father Valencia—who were part of the some of the expeditions from Guam to here, spreading the word, missionizing, bringing Christianity to the islands. And that’s when the people began to start to learn about Christianity.

|

||

|

|

||

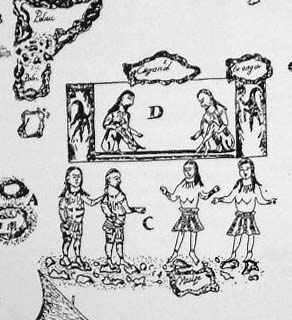

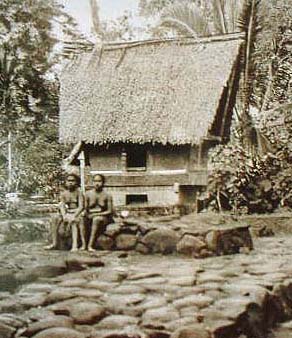

“The first thing that the missionaries imposed was clothing. My grandfather was a houseboy for the Catholic priests here during the German period. And when I talked to him, he said, ‘well the first thing they do is cut your hair short and give you clothes to wear,’—no more grass skirts, no more loinclothes that men wear. That’s how clothing really is an influence of the missionaries, and that’s pretty late. My grandmother was wearing grass skirts at the turn of the century, so clothing was really new here. "It's true, though, that when Captain Wilson came, among the items that they traded with the chief were their shirts, their coats, their hats, and the Palauans really kept them. You see some of the old pictures where the men would don a jacket going to a formal meeting but after, it’s held or kept for another occasion where they put it on."

|

||

|

|

||

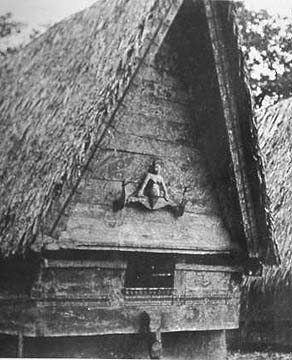

Practices concerning women visiting the bai were also quickly banned. Kathy explains, "The bai are men’s club houses. And there were these carvings of women on the end gables, that were supposed to signify that it’s a men’s club house. "That carving was the first thing that went when the missionaries came, because they thought that it was uncouth. You don’t have women’s parts displayed in the public. So what they did was paint over them, or find somebody to paint over or actually remove the gable that’s carved like that. "It caused a lot of commotion in the community, and it just didn’t sit very well with folks. Some of the missionaries started in Ngerechelong, the northern tip of Palau, they started their work and then because of the bai, because they wanted that woman painted over and so forth, they were chased out of Ngerechelong, and settled in Melekeok, and after they settled in Melekeok they came to Koror."

|

|

|

“They were well received in Koror. Koror was more familiar with foreigners, and by that time people were getting more used to foreigners. But this new kind of religion that they were bringing in, people were really very skeptical about it, though they were being polite. "These were foreigners and so you’re curious and you want something from them because they were bringing in a lot of goods—knives and clothes and all that. "The Palauans also were getting baptized a lot, but not really subscribing to the Christianity that was being preached, because we have their own religion and we have our own way of explaining our supernatural occurrences."

|

|

|

|

“When the Spanish missionaries were here, they taught the people to change," Walter remarks. "Local people in Palau, they have their own gods and totems: they have their own family gods, individual gods, village gods. And missionaries tried to changed that: they taught Christianity. Then a little later, new priests came in with a different mission: I guess they were playing the key part of trying to convert people so they could be controlled here.

|

||

|

|

||

|

| “Tattooing was one of the biggest arts of the culture, and they told Palauans it was not good. I think they thought it was probably associated with witchcraft and rites for the other religions. By the time the Japanese came, already the culture of the people had changed a lot from those outside contacts coming in. “I feel like Westerners came over here, they tried to tell the people that most of their of their traditional ways, their culture, these were no good. And they wanted them to adapt so it would be easier to control the local people here and their way of life. I guess they sort of thought about their own way of life as some better culture."

|

||

|

|

||

With the Spanish-American war in 1898, Spain made a quick and fruitless move to claim Palau, which was now heavily involved with German traders. The Germans would soon bring in their own Capuchin missionaries, but their main aims were economic. The Japanese would follow them in transforming Palau into a colony.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Airai Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||