|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

“Every history book you read seems to convey the idea that the islands were more populated before Western people came in,” Cal says. “I tend not to believe it, because just looking around, I think there are there are more people now on the islands than there used to be ten, twenty, thirty years ago. This is very threatening thing when you think about it. "Before, there was no such thing as ‘overpopulated,’ because of the way of life: people were living in a communal situation where everybody provided for everybody’s need. What’s there is for everybody. Everything is shared with everyone. So the little resources that is there is spread around and used as effectively and as wisely as possible."

|

||

|

|

||

“There are more kids. And people are marrying at a younger age. So my personal observation is that there are more kids born these days than before. Before, there used to be sort of informal ‘family planning’ to keep the population to standard. There was no spoken agreement that everybody had to keep their family within this size, but it was sort of an inherent, innate understanding that there is that responsibility. "Sometimes of course there are people who have big families, but people realize it when it happens and perhaps there’s no other way they can control it. “But today it is not consciously dealt with; people are just having children here and there. So I don’t know. I haven’t really looked at any hard facts, statistics, to compare the population."

|

|

|

“I would say roughly about f fifty percent of the Ulithi population now lives off island. In the past, I think close to one hundred percent were here, maybe one or two percent were out off island because of schooling and such. But now people have found residences in Guam, Hawai‘i, U.S. Mainland, and in Yap, so I don’t think it would be pushing it too far if I say fifty percent. And I think that will increase with time. “We still have less people,” Pedrus adds. “Maybe they’ll return. All depends on the negotiation for the new second Compact. If we’re still given free visas, then we are free to travel within the United States and probably it’s territories without any limitation. But I think that’s one of those things that’s going to go. I think there’s going to be a limit on your travel."

|

"Then you’ll have restrictions in the U.S. with employment. But since the beginning of the 15-year Compact, we have been free to travel, no limitations. And you can work too, if you go there. So that’s how some of use went there and stayed. I think it all depends on this Compact negotiations." “Unless the Compact situation with the U.S. changes,” Cal concludes, “probably that outflow will continue. The situation here is not providing the right incentive for people to stay. So they’re going out looking for better things, I guess. And when they go, they take the little ones. "And now, I think about four or five percent of Ulithian population has been born outside of Ulithi. We claim them because of their ancestry, but actually they’re U.S. citizens, because they’re born either in Guam or Hawai‘i or on the U.S. Mainland."

|

|

|

|

|

|

“What I see today is happening on Mogmog,” Mariano considers, “in terms of inter-marriage, is that people outside of the Ulithi Atoll are coming in to Mogmog and also people from different clans, even just among the Ulithi islands, are marrying into Mogmog and vice versa. The people of Mogmog are marrying out of Mogmog. So, there slight differences in the culture. How they believe, how they feel, how they value themselves as people of the chief island. "So now this varies. As Stanley has said, those few that are responsible to distribute the food are now calling upon newcomers, or people from outside of Mogmog, to step into this area to help them distribute the food. Whereas in the old days, they would certainly have refused to do that. The Mogmog people never asked anybody else to step onto that Rool’ong platform."

|

||

|

|

||

“This is also true with the distribution of food in the Men’s House, at the Men’s House platform. And not only on Mogmog; it’s been happening on all of these islands in Ulithi Atoll, because of this easy traveling, job opportunities, people going away to school. The few that remain on the island, now if they need help, they just call on anybody. There are not enough of the appropriate people to do that. “And so now, some people might think that their share is not fair. Their share may be given to a wrong clan. This could lead from some people just by looking at the way the food is distributed, and the actual people doing the distribution. Maybe they are not from the right place, and now they are assuming maybe they are doing it wrong.”

|

|

|

“Our population here on Mogmog has gone from 300 as far as I remember,” Juanito reports, “down to 200 around 1960. That’s the time we started going down because a lot of students were going off to school, and only some came back, the rest just looked for jobs. "Up until the 70s, most of our educated people stayed back in Yap, looking for a job there, or in Guam, even in Hawai‘i. Some even send money and goods to their family and relatives. So now, sometimes we go up to 180, especially during summer when these people come back to visit. Maybe for one month. And then going down to 120, 130. So it stays somewhat like that. “We’re okay as far as life is going now. Life before, we lived so much on what we grow and the fish from the ocean. Now more people are getting used to these new things that are imported, goods that come to the store. Many of our kids, when we don’t have rice they think we’re going to die because they don’t have anything to eat. They got used to eating rice every day so they don’t eat much of our local foods."

|

"Even now some of our kids, they think that like papaya, taro, breadfruit are not really food. They depend so much on rice. And fish, now they don’t really care too much about fish. They like canned meat and such. "I don’t blame them because that’s what we gave them almost every day. Like myself, my family, all of us are working and all our kids are in school. So when we come back from work, we have to cook something fast so we can have lunch. So we’re really spoiling our kids, giving them things that they can eat and go back to school.” “It’s changing too fast,” Manuel states. “Our the young boys and girls go outside for college and when they come back, they are looking for American food. Sometime, when they come back home they ask us for T-bone steak but we don’t have T-bone steak here. We have only fish. They don’t like fish! Sometimes they ask for ice cream. No ice cream here—it’s too hot—only fish!"

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Now we depend on something that we don’t have at home so sometimes we say in our language, wasool'a. Wasool'a means things that we don’t have at home but we like from outside. Very hard to have, to reach. Except if you have money.” “I think we’re having a problem with imported food here,” Isaac agrees. “I’m 54 years old, so I remember almost half a century’s worth. I remember before, when there were very few imported foods into the island, not too many people got sick. Now that we have more imported food, I think it contributes to bad health. We now have diabetes, hypertension; before, I think, only some cases of tuberculosis."

|

||

|

|

||

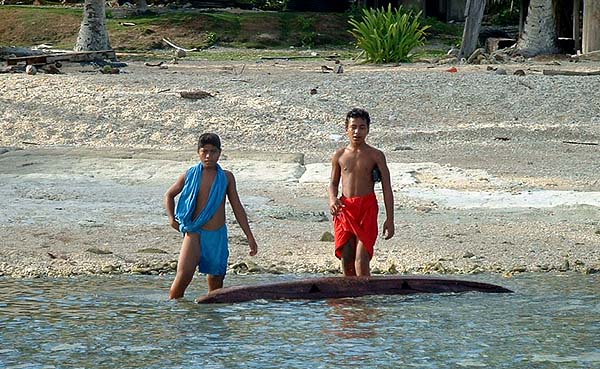

“Changes come to the island as a result of people going off to school. Some of them went and never came back. And those who came back, they brought back what they saw out there, and they tried to imitate it. For example, they’d come back here with a big boom box—radio, tape recorder–and they’d walk on the road with the volume up, blasting off. And people didn’t do that here before, youngsters didn’t do that here.” “It is much, much different,” Chief Yatch says. “We are learning part of American culture. You can see people here, they wear clothes. But we don’t care whether they do—women, we don’t care if they go topless, it’s nothing. Not like you Americans. Here, we don’t care. “I think while they are out and around, they become Americanized, Westernized. We are spoiled, you know, because of Western culture. But when we were at home they didn’t care. That’s the part of culture.”

|

|

|

“You can notice that some of our ladies keep on their shirts now,” Philip adds. “They are self-conscious about their bodies, which is very different than before, because we are used to seeing them without tops and without their bras, and they don’t mind because we’re used to it. But now they are very shy to take off their shirt. I think these changes have come because of travel and the television and they have seen other people from other places.” “Some people, they go out and learn things from outside,” Alphonso concurs. “Let’s say these that grew up in Hawai‘i and other states and they came back here, they try to apply what they know, but it cannot fit with us here. And some that grew up here and went to school outside, when they came back they’ve forgotten about how things work here. They just think about what they learned outside."

|

|

|

|

"This is a little problem for us here in Ulithi, because the living situation is completely different. In the U.S., with so many natural resources, you can do everything. Us, what? The fish? The commercial ships will come and take it all up, we will end up with no money. No money, no nothing. So we have to stick together. That’s what I believe. “I hope that the youngsters nowadays think about this. They go up to other countries and see all these good things there. Yes, they are good things there because there are resources there. But us? All of us like good things, but unless there is a way to get some money… "Since we don’t have it, we have to think twice about what you receive over there and all those things there. You come back and say, ‘ah.’ Sometimes I think most of us will run away from the islands, because we want things from outside that will not fit into our own islands.”

|

||

| |

||

The issue of clothing on Ulithi is a particularly acute reflection on culture and resources.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ulithi Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |