|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

“The first attempt to Christianize the people in Ulithi is the story about Father Cantova,” Cal says. “It started with this group of sailors cast away from the Outer Islands. During one of those yearly trips to Yap to pay homage to the people of Gachpar, some of those canoes lost their way and ended up in the Philippines. There, they were taken in by the Spanish missionaries, who took care of them. "The missionaries asked them where they came from. They explained their origins, how they got there, where they came from, and that’s the first time those Spanish people in the Philippines knew that there were islands out here that hadn’t been Christianized. So that stirred their interest to look for them."

|

||

|

|

||

“There were several communications with the Pope, and finally the Pope allowed them to seek out these islands. So they sailed from the Philippines to Guam and then from Guam to Ulithi. The priest’s name was Father Cantova, and he brought with him another Jesuit priest, Father Victor Walter, as his assistant, plus a Filipino servant and some soldiers. "After spending a few months trying to convert the people of Ulithi, he was sort of creating an imbalance among the local people. Some accepted the Christianity that he was preaching. Some were really against it. So he was, at that time, not very popular in Ulithi. “The division was based his Christianizing young, newly born babies. So that in and of itself sort of polarized the communities between those that were willing to listen to the priest, and those, usually older people, who were deeply rooted in the practices of the old ways, believing in their own magic and their own prayers.

|

|

|

"One could interpret it as the Spanish taking away some of their influence, because the old priests were the authorities then. But when the Spaniards came, they had to share that with Spaniards because they been taught something higher than the local priests. “So that created conflict, and to make the matter a little bit worse, some of those children died when they were Christianized, for reasons that we don’t know. Maybe because of the introduction of diseases that were foreign to them, by the priest and so with those who were biased, that really created a very tense relationship with the priest. “As far as I can remember from talking to our older people,” Issac says, “the conflict between the earlier priests that came out here, and the local people, it was a conflict of the religion and the culture. Before, one man could have two or three wives, but when Catholicism got here, they allow only one wife, and maybe people didn’t like that.

|

| |

|

|

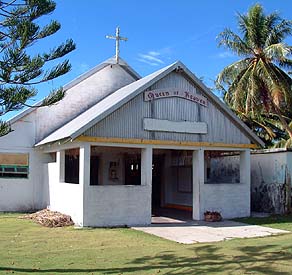

"Not only that, but the way of worshiping here: from stories that I hear, people worshipped their own Gods. They had names for different gods, one god for everything—god for the wind, and god for the weather. When Catholicism got here, they were told to worship just one God and I don’t think they liked that." “They set up their mission in Falalop,” Juanito says, “and tried to convert people there, but when they were low on supplies, Father Cantova sent Father Walter back to Guam to bring some supplies. And it was the Filipino assistant, I think, who went around and talked to the people. Maybe he didn’t like those priests. He talked to the people and then finally they came over here and told the paramount chief that they wanted to kill Father Cantova, but not on Falalop—they didn’t want to get the blame for that. They came and asked permission from the paramount chief. "Then they lured the priest over here and they killed him here on Mogmog. And then after they killed the priest here, they burned down the mission in Falalop. That’s what I heard."

|

||

|

|

||

“People hated him,” Mariano adds. “When he would kneel and pray, they would jump on his legs and try to push him, and so only a few from here turned to him, and listened to what he had to tell them. The people of Mogmog killed him. And when the boat returned, it couldn’t find him. The small church that he set up here—not really a building, probably a small hut— the people of Falalop had destroyed it.” “When the other priest found that mission already burned,” Juanito says, “he went back. And somebody came after them on a friendly mission, on a field trip out to all the islands to meet the people there. Maybe after that we came to understand about these people coming from outside. "But the first people, maybe that’s where we got the impression that they are bad people, maybe not treating islanders the way we expect them to. Maybe that’s why we didn’t like them. Plus we believed that they brought in something to change the way we believed in religion. Maybe that’s why we didn’t like priests.”

|

|

|

“We know where they buried Father Cantova at the end of this island. That place been eroded during typhoons, so the exact location of the grave, we don’t know. We have two cemeteries that have been here since a long time ago. One at either end of Mogmog. He was buried in the cemetery, and also they put a small hut over that grave. Now nobody knows the exact spot where the grave is, the old one. It may have washed away, we don’t know." “That sort of ended the first attempt to Christianize the people in Ulithi,” Cal says. “I think there were some preliminary investigations there after but there was no retaliation like happened in Guam. Finally the real Spanish administration came, and the priests again started to go out to the islands and begin converting.” “That time,” Mariano explains,“They worked through a native who was residing on either Guam or Saipan at that time. He came as a helper to the island and that’s how the Mission started up again. And people would listen to the priests because of this guy, who was helping explain the purpose of the missionaries’ visit.”

|

|

|

|

|

“Of course the Spaniards at that time, they had a strong Catholic country,” Cal suggests. “I guess everywhere they go they tried to introduce Christianity and Catholicism to the people there. Even up to German times, the Spanish were allowed to come here to spread Christianity and to preach, and that’s how they got their influence out in this region. Through their administration and the ensuing Germans administration, they were allowed to stay to Christianize the populace out here, to preach and expand Christianity. “The Spaniards who were here before the Japanese, they were really strong and influential, and that’s how a lot of these Spanish names found their place here, because they were trying to get parents to take the names of the saints and Christians from the Western culture. So, they influenced the people very strongly.”

|

||

|

|

||

“Initially the Japanese let them stay, but then when the world politics started getting hot, I heard that some of them were killed off as suspected spies. And some of them were just outright deported back to Spain. As the Japanese tried to expel all the Capuchins and all the Spanish priests, in the back of people’s minds there arose the need to worship without the presence of a priest." “During the Japanese time,” Juanito recounts, “we had this Spaniard and one American priest in Yap that used to come out here maybe once every three months, and there were some people already Christian during that time and they would come and work and go back to Yap. Two of them, Father Bernard and another priest. Chief Taithau’s uncle worked with the priest during that time and he did a lot of translation on the catechist book. He translated it from Yapese to this vernacular."

|

|

|

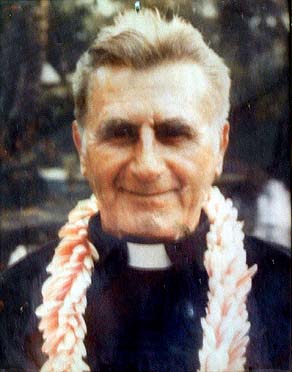

“I think at by the time of the War, three fourths of the people here were already Catholic,” Alphonso recalls, “because the Spanish priests from Yap came out to Ulithi and we already had our own Catechist school.” “There were some priests who came to Yap before the War,” Ignathius remembers, “and one of them came out here, but only a few became Christian at that time. So we just did our own religion, until after the War when Father Walter came. Then he started converting people. I think he was with the military, and had been in the Philippines sometime during the War, and then after that he came here.” “During the American time,” Cal says, “the priests started coming back again. And the priests that came out with the Americans were mostly schooled in the old Spanish practice. They were very strict, adhering to the old Catholic traditions of the Spaniards. So it sort of re-continued from the way the Spanish had taught; there were small changes but, basically they were the same."

|

|

|

|

|

“When the Navy came here,” Juanito says, “the Navy priest start converting more people. When the Navy moved out, the late Father Walter came out around 1948. He stayed out here, converting almost all the people. He even went up to all the neighboring islands every time the field trip ship went out there, until he died in the 1970s. He has his grave here at the church on Mogmog. When he got cancer in the throat, he went back and died in Buffalo, New York. They sent the body back, and we buried him here."

|

||

|

|

||

“By the time of World War II,” Cal says, “there were of course a few people who were very resistant to the idea of being converted. And they maintained their traditional beliefs. Up until a couple years ago there were still people living in the communities who just refused to be Christianized. But mostly the people converted to Catholicism, or just adopted the rituals of the Catholics. There must have had a very strong, influential priest back, then because most folks were very adamant and religious church goers." “After the War, there were still people who would think they were practicing ‘magic.’ They were still doing magic, but there were some practices that were no longer done. ‘Magic’ is not really the best word for it. There are some terms that give the wrong impression. There are some of the practices that are attributed to the Devil and to ‘magic,’ but when you think about it, they’re nothing more than psychology."

|

|

|

“I knew a lot of people, including my grandparents, could read colors—they would look at the color of the clothing you have on, and tell you what you’re up to. And they could open your basket and look inside and could tell you what kind of person you are, what you’re up to that day, or what you’ve been up to, by just looking at the content of your basket. “My grandmother was gifted. She had a family gift that she learned from her past ancestors and it passed down all the way to her, and at the time my grandmother, that’s when all of this issue of Christianity versus devil’s worship and magic and stuff, it was really strong. So that was basically abandoned, because they claimed it’s the work of the devil."

|

| |

|

“I think a lot of important skills and practices were lost then," Cal concludes. "Some of them because of the way they were practiced, they were misinterpreted as the work of the devil, but it’s all science, in my opinion. Careful observation and deduction, and logical sequencing, and all of those put together and you come up with a possible solution to it, or possible explanation.”

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ulithi Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |