|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

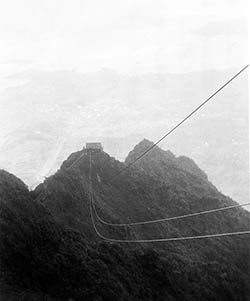

The Omega Station, left, commands the upper reaches of Ha‘ikū Valley. “We have a couple historic sites that are more modern,” Mahealani begins. “The Omega Station [formerly the Naval Radio Station] and the Ha‘ikū Stairs and the Quarantine Station is part of that whole complex. They developed the property for military purposes. Actually they started anticipating before 1941, anticipating they would need facilities to protect the islands from attack and unfortunately they didn’t protect it from attack because the building wasn’t built. The station wasn’t built until 1942, I think.”

“The Ha‘ikū stairs was erected by the Navy as part of the construction of the radio transmitter station. They needed to put a shield of copper cables below ground and overhead so the top of the mountain connected by cables to the station and there was a cable car that came down. The Ha‘ikū Stairs were built so that they could put in the anchors at top of the mountain with the cables that connected to the station, so huge enterprise. "The station was built to withstand a 200 pound bomb so they’ve got some walls that are ten feet thick. The Ha‘ikū Stairs is so solid, the only thing that gets corroded once in a while are the railings, but the stairs themselves are the kind that bite into that mountain at least three feet deep, those nails that hold those stairs. I’ve been up there a couple times.” John tells us the history of the station: “When the War started in 1941, the military decided they needed a very long-range transmitter that could reach the ships and submarines in the West Pacific. So they built a very low frequency transmitter with this big antenna, stringing the antennae across the mountaintops. Ha‘ikū Valley is formed in kind of a horseshoe shape, so there were two ridges where they could string the antennae across. They could build their transmitter building with all the associated equipment down below. The facility was built and it worked. It was a top-secret project, so it wasn’t much talked about during the War. “But after the war the public found out what it had been doing--reputedly able to transmit to submerged submarines in Tokyo Bay. Because it was a very low-frequency transmitter, they needed very long cables—more than a mile long—reaching from peak to peak across the valley. So there are antenna anchorages on the other side of the valley as well. It’s not very easy to get to; there’s no stairway going up there. “They started thinking about it in December right after Pearl Harbor, and they actually got started on it in early ’42, and I think it finished by at least ‘43. It was an emergency effort. It suffered a set-back once by a damaging fire that they thought might have been sabotage but that was never confirmed. It burned one of the main layers of technology, and they had to reorder expensive equipment. “There’s a wonderful story of the two guys that originally climbed to the top by driving spikes in the side of the mountain, climbing up those and driving more, hauling up primitive wooden ladders, then climbing higher. It took them twenty-one days to get to the top. And once they did that, it was possible to build a more substantial wooden stairway bottom to the top, and eventually a cable car that was used to haul workers, equipment, and concrete. It was quite an effort.

“The power for the cable car was at the base of the stairs. The cable car ran only to the Upper Hoist House where it intersected a second cable system that was used to distribute concrete and equipment the rest of the way to the top and around the ridge to the various antenna anchorages. The antenna cables were more than a mile long, and heavy, so the pull against the ridge was enormous. To manage that, they planted the anchorages in huge masses of concrete and hung counterbalance weights on the opposite sides from the antenna cables. “The wooden ladders lasted until metal steps were installed in about 1953. They had already used metal structures up on the ridge and at the top. And as a matter of fact I was in touch with the architect who designed the metal stairs. They’re sometimes described as ‘ship’s ladders’ in the sense that they have a firm metal form, round railings, non-slip or slip-resistant stainless-steel steps. When I first climbed in 1984, some areas had slumped a little bit. Some were a little crooked, but it was solid. I mean, they are held in place by three- to five-foot metal stakes that are driven into the mountain to hold them on. It’s a very, very firm.” Read the history of climbing the Ha‘ikū Stairs “Then when the Navy left, the Coast Guard took it over. The Coast Guard didn’t need that kind of radio transmission. Technology had gotten a little bit more advanced, so they closed the station down. But they had been experimenting with long-range navigation—what became the Omega. "The Coast Guard had been involved in that, so over a period of time, they developed enough technique that it became one of (I think) nine Omega stations all around the world where they could transmit and get pretty good navigation. By triangulating from at least three of the stations, they could find within a mile or two where they were. And then of course satellite navigation took over from that, so Omega was not needed anymore. And so the Coast Guard closed that down.” “My father was saying it was very important,” Rocky states. “We had family living in there before the military took it over. In fact, my father, my uncle Billy, my uncle Sonny, and one of the cousins, last name Kea?, they took the military up on the ridges. That is how they built the cable car. My grandmothers, they said Grandma tutu would just stay down and pule for them because they knew the way. If you look good, you can see the stairway, right? On a bright sunny day, we can see the glitter shine. All the rest is on the other side of the valley. Along the ridge, there’s all rails, and my father them helped to put it up. They helped to build it for the cable car. When they did the H-3, they took the cable car down because they said the electricity was not good for the passing cars. They should’ve left the cable car.” “The historic buildings have been all but destroyed, essentially,” John laments. “The transmitter building was built to be bombproof. It has, as I recall, six-foot-thick concrete walls and nine-foot-thick ceiling. So it is almost impossible to destroy the structure. But the inside is completely wrecked. Beautiful electronic equipment torn out for the copper, walls, ceiling, windows broken and smashed, even set afire. "The inside of the building was just gorgeous—all this beautiful electronic equipment and oh, it was so pretty. And it was just trashed—just totally, purposely trashed. Fires built in the sink. Walls and windows smashed. All the copper—all the beautiful copper tuning coils—they ripped that out to sell the copper of course. Made me cry.” “I’m hearing my uncle talking about the treasures in there,” Rocky recalls. “I was a young girl, I don’t know what treasures they’re talking about. Growing up now, this age, I know what treasures they’re talking about. It was all the copper in the walls. They literally took the Omega Station apart. Because when the military left that, the last one to have it, I think it was a Coast Guard, it was pristine. You could move right in. We want to build a museum over there not only for our cultural artifacts, but also for the military. It was important to the military. We could work together.

“But if you see what it looks like now, it’s a shame. I have a relative that was stationed there for five years, and when he went back there, he couldn’t believe it. He said, ‘I can’t believe what they did to this.’ You got to be careful. You can’t just walk in there without a flashlight because my father said there’s also rooms under the floor. There is openings you can step and you can get hurt. You can get impaled, in fact, lucky we had our flashlight on in there one day because we noticed that too. “You can see the inside walls where they stripped it all. And right smack in the middle of the Omega Station itself, there was this real big room. Those days, it’s supposed to be about ten feet thick, but the outer walls, if you walk around, it’s like three ft thick. But right in that one middle section, it must have been at least ten feet thick, and that is where all the copper wires. And then I found out my father them, that was what they were talking about. The whole thing was lined all with copper. You know how expensive copper is nowadays. “Ha‘ikū Stairs and the Omega Station were both eligible to be placed on the National Register,” Mahealani says, “but never nominated by anyone, the Navy or anybody. But I believe the Navy did indicate that they believed that that was eligible and I don’t know if DLNR has ever done anything about it, but that’s something to pursue.” |

|

|

Meanwhile, out in the bay, another transformation was taking place. Under private ownership, Moke o Lo‘e was turned into "Coconut Island."

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

|

||||

Copyright 2019 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||