|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

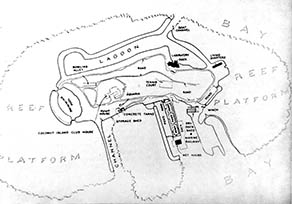

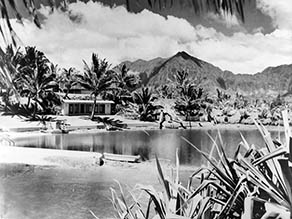

“Moku o Lo‘e [Coconut Island] is an island that once was home to a chief and his family,” Mahealani says. “Descendants of that family are the Gay family from Kaua‘i, the Gay and Robinsons. I met one of their family members some years ago and he told me that there was a large heiau on the property. And the chief who lived there had an impressive view of the entire bay, and that was his domain, so maybe he was the chief for the Ko‘olaupoko moku. Anyway, he lived there." Moku o Lo‘e had been part of Abner Pākī’s mahele lands in He‘eia—lands which transferred to his daughter Bernice Pauahi Bishop. Bernice herself had planted the namesake coconut trees on the island during a visit in 1883. The Bishops leased some of these lands, including Moke o Loe, to the He‘eia Sugar Plantation Company, which struggled financially and finally foreclosed in 1885. The lease was purchased by Marcus Colburn in 1889 on the condition that they “protect and take good care of the cocoanut trees now growing on said island.” After Pauahi’s death, her husband Charles Bishop deeded the lands of He‘eia over to the Bishop Estate. Bishop Estate sold the island to Christian Holmes II in 1936, though various people had lived there and/or utilized the island in the intervening years. Christian Holmes Sr. had been a doctor to the Charles Fleishmann family, and married Bettie Fleischmann, heir to the Fleischmann yeast company fortune. Chris Holmes of Moku o Lo‘e was one of their sons. He was fascinated with the Hawaiian Islands and moved his home to an estate in Waikīkī in 1933. “The original owner of the property, Chris Holmes, my auntie used to be the cook and my mom was a bartender,” Alice says. “ She met a lot of presidents, a lot of presidents. She particularly talked about Truman. That’s a nice place. It was beautiful, not now, not now that the university got it....oh they used it for what kind of job they’re doing, so it's fine but it was beautiful. They’re beautiful, we could go there, play. He was fine though, Mr. Holmes, he also had a home in Waikiki." “Chris Holmes was an heir to the Fleischman Corporation,” Mahealani explains, and he owned Moku o Lo‘e in the ‘40s and ‘50s, and he eventually sold it. But my grandma told me stories of having been there for the parties when she and grandpa were invited to his parties, fabulous parties. They would do these water ballets from the '50s and '40s. They have a little like a lagoon there. So like my grandma told me there were fabulous parties and he had an elephant with him on the isle. My uncle had exotic animals there so I think that quarantine station might have been built because he had all these animals coming down. “They used to load the fish catch at the piers there and in here. Along the coast they had a lot of little piers where they loaded up fish from the catch from the local fishermen. I remember the little mom-and-pop stores sold fish. Most of those were run by Japanese or Chinese. DOTE store was where Jack-in-the-Box is now. I used to sell newspapers in front of DOTE store when I was a real little kid. Kāne‘ohe was kind of small town back then still, yeah. We had a population of I think 3000. But it was the whole Kāne‘ohe Bay. That’s why I said everybody knew everybody." “My mother worked there,” says Rocky. “My mother was a maid. Chris Holmes owned it. And then after Chris Holmes sold it, he sold it to these Japanese people from Japan. Which they are good people. My sister-in-law was a maid over there, too. My mother worked for a couple of presidents that came there. And I swam, used to race as a young girl, all the teenagers raced across from Yacht Club Road, Lilipuna Road to the island. It was nothing to us. We’d swim back and forth, we’d race. And then on day, one of my friends said the largest shark he ever saw in his life was between Coconut Island and the fish pond. I said ‘Oh man, lucky that thing never bothered us!’ But then my husband said there are also the shark caves under there.” The island was evacuated shortly after the Japanese attacks on Mōkapu on Dec. 7, 1941. Christian Holmes returned in the summer of 1942, but his heavy drinking made him paranoid and few visitors were welcomed at the island. Under treatment for severe depression, Holmes died in 1944 in New York City at the age of 47. The executor of his estate leased the island to the U.S. Government in 1945. The island was then used primarily by Army Air Force personnel for R&R, and the big parties resumed. But in a few years the infrastructure limitations of the island (such as sewerage), along with the island’s isolation from the rest of O‘ahu, led the military to abandon the island at the end of the war in 1945. The island, it’s facilities falling into disrepair, was briefly open to the public. Around 1946, a small group of entrepreneurs including Edwin Pauley bought the island with the intention to turn it intoan international country club. But within a year, it was clear that they were not going to be able to sell enough memberships to maintain the island. A hotel was opened in 1950, hiring workers from He‘eia and Kāne‘ohe. Clark Gable spent part of his honeymoon on the island. But the property deteriorated under the management and the hotel was closed in 1951. A number of ideas for how to use the island were then floated, including as a home for preacher Father Divine and his mission, as a luxury military facility, a new hotel, as a home for children with cerebral palsy, and as a nudist camp. At issue were the lands Holmes had created by dredging and filling. These had never been propertly assessed and taxed, and their ownership was unclear. Shares in the ownership of the island changed hands with various schemes. In 1964, a small beach on the island was used for an opening shot in the TV series “Gilligan’s Island,” and while no actual episodes were ever filmed there, that association has stuck. Meanwhile, Edwin Pauley and his family had begun summering on the island since he became a co-owner in 1946. Harry S. Truman spent a month on the island with the Pauleys after the end of his presidency in 1952. The Pauleys continued to enjoy the island with their esteemed friends and guests through the 1950s and into the 1960s. But the idea of developing the island slowly died, hastened by the arrival of Navy jet fighters to the Mōkapu air base, and their thundering noise as they practiced take-offs and landings low over the island. A small crew continued to live on the island and take care of the maintenance. But Hurricane ‘Iwa in 1982 did extensive damage to the buildings.

In 1987, during what was known as the “Japanese bubble,” Japanese developer Katsuhiro Kawaguchi purchased the island for $8.5 millon. Various development plans ensued, including (once again) a hotel and a dolphin research facility. A Hawaiian fishing villages was also imagined. But the island had been zoned a conservation district, limited development opportunities, and the burst of the Japanese bubble meant foreign investments in the islands were no longer so profitable. Renovations of the existing facilities was estimated as high as $20 million. In 1995, Kawaguchi sold the island to the University of Hawai‘i Foundation for $2 million, who then leased it to the University of Hawai‘i. The Pauleys had already been sharing the island with the University’s Hawai‘i Marine Laboratory. Like Chris Holmes before him, Pauley was avidly interested in marine life and had become friends with Dr. Robert Hiatt, the founding director of the Laboratory, and invited him to move the lab out to Coconut Island around 1951. Hiatt took over several buildings built by the military during the war. A the time, there were no marine labs in the world dedicated to studying corals. The Lab continued operation through the islands turbulent changes of the 1960s-1980s. “Because I have relatives, my family dates back a long way in Kāne‘ohe,” Jo-Ann states. “I would go fishing on the bay every weekend and I would see this island that we were not allowed to visit, and I wondered about it. I was always told that there are people that live there, and we just weren’t allowed to come on board. So when I did make my first visit to Moku o Lo‘e, it was interesting, but it was also quite sad. The buildings had fallen into disrepair, there was the Bridge to Nowhere that you don’t see any more—it was a bridge that went through the lagoon and you almost took your life in your hands walking across it, it was wobbly and falling apart. That got removed quickly once I became director and we put in these pontoon bridges that really do work quite well.

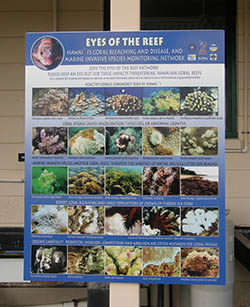

“There was some concern whether the island should be a marine station—not an institute of marine biology—where faculty would be housed on the main campus and you would go to this marine station when you needed to, to do the research that the island afforded. But that was not what I thought the Pauleys or the original founders of HIMB wanted, and not what I wanted if I was going to take over as director. The place has grown dramatically with an infusion of funds and new faculty. “It’s been a massive overhaul. The main building that was there was falling apart and we invested a huge amount in renovating that building. The point was falling apart, and we were in the process of getting that renovated. And the pier that linked the island to O‘ahu, we needed that pier to take the boat to the island, that got condemned. It was held up by falling concrete. “We got a promise from Hawaiian Telecom to provide us with an undersea cable, and the university got on board, and the State legislature got on board, so that we could drill underneath the bay without disturbing the coral infrastructure surrounding Coconut Island. We received an NSF funded grant to provide internet connectivity to the island and now HIMB is connected with fiberoptic cable to the main line to the University of Hawai‘i. “When I started, I was really naïve, I’d been on the job for eight days and I accepted a speaking engagement with the Kāne‘ohe business community. And while I was there, all the anger at HIMB came out, and I didn’t know it was that bad. They blamed HIMB for the invasive algae that now is part of our bay and has spread around the island of O‘ahu. (None of the HIMB faculty were involved in its release). "They blamed HIMB for not studying the Hawaiian mullet and why the mullet were not coming back to the bay. Hawaiian mullet usually travels to Wai‘anae, get fat and then comes back to Kāne‘ohe Bay to spawn. Auntie Carol Bright used to talk about the times when the streams in Ko‘olaupoko were not all lined with concrete to prevent floods, and the mullet would come back in such numbers that you would hear them rustling up the streams to spawn. “At the Kāne‘ohe business meeting, they asked me these questions—I thought they were going to ask about the future of HIMB, a kama‘āina girl coming back and all that—that was not in the discussion at all. They were so upset at HIMB that a group that Windward Community College formed an organization that loosely translated meant ‘Keep your eye on Moku o Lo‘e.' They wanted free access to the island and I talked with them. I said ‘you can’t have free access, we have graduate students living here, we have research. Within 25 feet of the reef you cannot fish. It’s not that I want to keep you away or that we’re doing anything secret.’ We didn’t have any funds at that time, so I was the most highly paid tour guide they had. There was no one assigned to do it and I wanted to make sure that the community felt welcomed. It took ten years and it took us working constantly to engage the community. “We now have four designated marine educators. I was able to work with Senator Clayton Hee, who granted us those positions over time, and HIMB educators have been wonderful communicators with the community. HIMB is definitely working to develop education programs, with funding from the federal government to develop marine education with Castle High School and the other local public schools. “Now I think it’s future with the community is sustainable, and that’s what I think the island is meant to be. The elders have been consulted every which way as we moved forward, and I think that the elders would like it now. It’s meant to be a source for helping to conserve our marine resources in the coral reef environment as well as provide graduate education. I think HIMB is doing a good job.”

|

|

||

|

The issues of the 20th century bring us to the issues facing He‘eia in the 21st century. In the next chapter, we learn about what is on the minds of our guides today.

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

|

||||

Copyright 2019 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||