| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Hā‘ena's neighbors fall into three categories: ahupua‘a in Halele‘a to the East, in the Hanalei direction; valleys to the west, in the Nā Pali direction, and the nearest town of any size—Hanalei itself. In the first group are two nearby valleys, Wainiha and Lumahai. These valleys reach back deep into the heart of the island, and are important for their historical relationship with Hā‘ena. The ali‘i Abner Paki, and the konohiki Kekela, were associated with these two ahupua‘a as well as with Hā‘ena. Wainiha also shares many traditions with Hā‘ena, from the Menehune of ancient times to the Hui Kū‘ai ‘Āina management system of recent history. The sense of belonging to an ahupua‘a and respecting one’s neighbors is captured by this passage that Carlos recorded from kupuna Elizabeth Mahuiki Chandler, known to everyone as Kapeka:

Hanalei, the nearest town, lies approximately nine miles and five ahupua‘a to the East from Hā‘ena. Today a small commercial center serving the sparsely populated North Shore of Kaua‘i, Hanalei sits in a broad coastal valley and is famous for its beautiful mountains, waterfalls, and taro fields. Its lushness is a result of the frequent rains for which Hanalei—and the Halele‘a district generally—was known in traditional chants and songs. Here are three examples from Pukui’s collection:

Here are the names of the neighboring ahupua‘a from Hā‘ena eastward to the next moku, and their meanings according to Place Names of Hawai‘i:

Nearby Lumaha‘i was once known for a certain kind of shell made into hat bands:

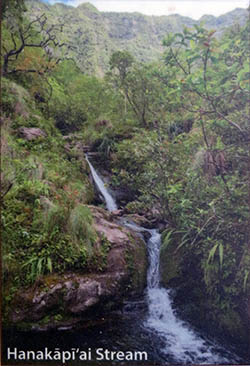

Going the other direction, one immediately enters the moku of Nā Pali (the cliffs). There is no road, only a trail. “That isn’t really a true Hawaiian trail,” Ka‘iulani says, “it was built to catch an outlaw.” She refers to the story of Ko‘olau the Leper, who fled to Kalalau in the 1890s to evade capture and quarantine on Moloka‘i. “The moku of Nā Pali is a small district facing northwest,” Carlos says, “and named for its rugged coastline of spectacular sea cliffs and hanging valleys. This name is shared by no other moku in the Hawaiian Islands.” First is the valley of Hanakāpī‘ai (“bay sprinkling food”). This small valley is accessible by the Nā Pali trail and by boat, but not by road. Smallness, yet sturdiness, appears to have been a characteristic of this valley:

Past Hanakāpī‘ai, the trail crosses two more ahupua‘a before reaching Kalalau:

Whatever the traditions of these areas, they have been lost. Several miles of trail beyond Hanakāpī‘ai is the broad valley of Kalalau. Once a well populated and productive valley, this was the farthest one could go down the coast on foot. Consequently, a strong bond developed between the people of Kalalau and the people of Hā‘ena, at either end of the trail. The valleys of Nā Pali are well watered with permanent streams, good agricultural soil and abundant marine life. According to a sign at the head of the Nā Pali trail, “Hawaiians continued to live in the valleys of Nā Pali until 1920, growing kalo and fishing for subsistence and trade. Others tried growing coffee in Hanakāpī‘ai and Hanakoa in the late 1800s. Their ventures were short-lived, but the coffee trees remain. “By 1900, it was a hardship for families to live and farm along this isolated coast. Many moved to the towns of Hanalei and Waimea for jobs and schooling. The agricultural fields were abandoned and became overgrown. After 1920, cattle grazing in Kalalau valley was the only economic activity along this coastline.”

The broad valley of Kalalau rests at the end of ten miles of winding trail from Hā‘ena. “The ancient connection between the people of Hā‘ena and Nā Pali district was one of longstanding duration,” Carlos explains. “A unique, practical, reciprocal relationship evolving in historic times joined Hā‘ena people and residents of the isolated valley of Kalalau, located at the end of the eleven-mile-long trail leading deep into Nā Pali. Kalalau valley, once home to a thriving population numbering well into the hundreds, continued to support a small community of permanent residents until the early 1900s. “The fertile valleys of Nā Pali were somewhat more isolated from the rest of the island in post-contact times. They were only accessible by a narrow trail alternately winding itself in and out of the valleys, clinging to precipitous sea cliffs. During the relatively calm months of summer, a few select places could be accessed by sea. An incredible number of stone wall terraced fields are found in these valleys, now devoid of any permanent human residents. The ancient stone-faced terraces of Nā Pali stand in mute testimony to the industry of the people and the intense cultivation of those valleys in pre-Euro-American times. “Hā‘ena residents would, from time to time, go into the valleys of Nā Pali on excursions, hunting feral goats and fishing the less intensely used areas there. The people of Kalalau raised their own horses and kept them in their valley, utilizing them in much the same manner as the people in Hā‘ena. Visitors from Hā‘ena would often stay several days and sometimes a week or more on these jaunts. Often, quantities of fish or goat meat would be accumulated early on and would be ready to be sent home before the hunting party was ready to leave. There were no stores in Kalalau but in Wainiha, the neighboring ahupua‘a east of Hā‘ena, was a store stocked with kerosene, flour, and canned goods—items that had either become necessities or welcomed as luxuries, providing a change from the traditional diet of fish and poi.” Kalalau's dramatic landscape and its location on the rugged, weather-beaten Nā Pali coast perhaps gives rise to the following saying:

But many of the Hawaiian expressions mentioning Kalalau engage in word-play with "lalau," to wander astray:

“My mom and dad are both from Kalalau,” Michael tells us. “I think Samson Mahuiki, his dad La‘a came from down Kalalau. Some families are still around, their ancestors came from Kalalau. Kalalau was great. I used to go hunting with the old folks, my dad guys, and cowboys from the west side will come this side on a Friday. They all have mules and all. My first time, my mom said, 'Oh, you’re going hunting with your dad on Friday? Oh, great.' And then I see all these guys coming with trailers and mules. “His dad used to tell me when, where, and how to go for block the goat. He never took me in there but I listened to his story, what he told me to do, and I went. I found all the places where the goat would run. So, I would wait here and let the other guys chase them, come to me over here and then I’d take them out over here. So yeah, Kalalau is beautiful.” “Once you go Kalalau,” Samson says, “there’s that nostalgia, you stay away too long. There’s something in that place that you gotta go, eh? I think Dr. Koontz is one of the guys that always went too to, liked the outdoors. Even me, I don’t know why I used to go back, but once you see that place, oh!” |

|

||

|

Nested within the moku‘aina of Halele‘a and positioned midway between Hanalei and Kalalau, Hā‘ena's unique character as a native place unfolds.

|

|

||

|

|

| ||

|

|

||||

| Copyright 2018 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||