|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Kaua‘i’s only lagoon, Kai-kua‘au-o-Ha‘ena, ‘lagoon sea of Ha‘ena,’ protects Makua Bay,” wrote Uncle Bruce Wichman in his book Kaua‘i: Ancient Place-Names And Their Stories. “Papa-loa, ‘long reef,’ encloses the lagoon. A fishing hole near shore is named Ka-‘aulama-poko, “light from a short-burning torch,” because it can be fished at night using a kukui nut torch, which never burned for very long. Ka-lua-‘aweoweo, ‘'aweoweo hole,’ is the fishing hole at the farthest point from land. The ‘aweoweo (bigeye fish) gather in this grotto. It is a twenty-inch-long fish having white flesh. It was eaten raw, cooked, or dried. A large school of young ‘aweoweo, called ‘alalauā, swimming into a bay was an omen of the death of a high chief.

“At the time they fished two kind of ways,” Uncle Tom explains. “They had their kahuna for bring the fish inside like I’m telling you now, in this area had plenty of people. Where you cannot be sarcastic. And that’s the reason why you got to respect the elders. We get dirty hell from our parents or our tutus, if you ever talked funny kine. “The ‘alalauwā is aweoweo—the baby kind. Get plenty come, like all up here would be red with that thing, something would happen—something drastic would happen. Tidal wave, hurricane, whatever—that’s a warning. And I know that. But most that time, the tutus can tell you because they foresee these things.” Here are two Hawaiian proverbs regarding the ‘alalauā:

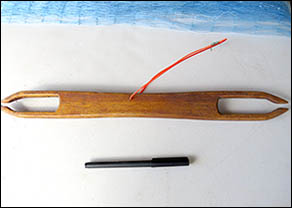

“Generally there were only two real kapu or restrictions put in place that I was aware of in some of the reading I have done, Presley adds. “One regarded fishing the ‘opelu, a smaller mackerel-type of fish. You could fish it only six months a year. And then the aku, six months of the year. “We did ‘opelu fishing, but I wouldn’t say very often,” remarks Uncle Tom. “But we had the net to go trap them, enough. Could go surround with the big eye, the ‘opelu won’t get close to the nets, so you can go net them with the makapili, that’s what happened. Like we used to get special net, like one inch eye, to go trap them. But at that time, when we did it before, it was only for kaukau, so you would go over there and go kill a pile, you make one big pile—twenty, thirty baskets from one big pile. That’s plenty. You get one pile like that, and most of the time they come in plenty, the bay, Hanalei. But today it’s a little different because I guess the water is contaminated as far as I can see. Ocean water is contaminated. That’s the reason why no more that much fish. Even over here. But my time, fish was plenty. We come over here with my Dad, one throw on the mullet, one bag.” “I am an expert fisherman myself,” Uncle Tom states, “and still fish. The knowledge I am applying with these people today, that came from way back, I learned the habits from my kūpuna. They were my mentors. I fished with different ones. Like Hanohano, he was born in Kalalau. So he knows this whole coastline to Miloli‘i! We used to fish this whole coastline to Miloli‘i, and that’s how we learned the names of the coastline. But I didn’t fish much besides right in this area. Up into the boundary of Ha‘ena. Right within our area, because we didn’t want to, like the Hawaiians say, maha‘oi: ‘No maha‘oi somebody else’s place!’ So we stayed in our area. So that’s what made me think about doing the rule for us in this place.” “I’m not one big game fisherman, I’m a shoreline fisherman, I stuck to the shore. I don’t say we never go went there, go hook aku and ahi like that. Very few times we went out there because my brother had a big 24-footer. We used to just go out there and get couple coolers, and that’s good enough already. We never did sell the fish. “At that time we used to go catch the aku, and a few times we catch ahi, because we no more the equipment for that. Ahi is big. I like dragging one line or something, but if you go with the reel, no can. Need one big reel for the ahi. Aku, we used the dragging the line, like we drag maybe four lines in the back. You can hold on the line and when they bite, you pull them inside, The aku is small, like 15-20 pound, nothing that! Just pull them in, and more fast to do that, the aku. Hand line, you just pull them in and that’s it. “They used to go hook aku,” Kelii adds. “they would go bottom fish for moana, moana kale, nohu—nohu is a type of sea bass. Also they the go catch crab, kona crab. And then besides aku, we catch the ahi too. For us, we go hook akule, And that’s another thing now is we’re trying to bring back. Carlos has a double hull that he brought back and we want to bring it down this summer to go take out whoever who wants to learn to fish in a canoe.” Read about night fishing for ahi. “And we used the boat to catch the turtle and stuff, like we used to use net. Because get plenty people they like eat turtle, to go catch the turtle, make net, I would say about fifteen feet. Look where that turtle’s head comes up, just shot ‘em. Go over there, maybe you get fifteen turtle, and we only going to take one for us, because we no like go harpoon that turtle. It’s only for us. And then if somebody is with us, we go catch one more, maybe dive inside there and tie them up or something, so we get two. We give away one and one is for us to take home for eat, for the family. That was our meat, the turtle.” “The canoes that I saw when I was growing up, they used to make the kind redwood kind. Redwood, flat bottom. And was always outrigger on one side, that’s it. Hoe. And we had regular hardwood paddle for that. You know big ones. [Maybe 16-inch diameter and 20 inches tall, the blade]. My dad had small ones and big ones that he used too. And the thing was kind of tapered from the center, come narrow on the outside edge. Go outside Kū‘au. That’s where we used to go fishing outside, go out. Kapaiki. If you go over there either that or Muliwai. We used to go outside over here and go fish with the canoe. Not anywhere else, only inside here. To get across the channel. That’s what it was, or go hook for hīnālea. We used to use that boat, but we make sure no make mistake, bumbye you go upside down!” Samson’s father fished commercially, especially for akule. “Being a kilo, that was maybe his skill,” Samson says. “Very skillful for discern type of fish, from viewing. See, everybody can see red and whatnot, but they cannot tell you what kind of fish exactly. Maybe this, maybe that. The only thing I know he told me: the smaller the fish, the edges are going to be more distinct. And it stands to reason, eh?” “But we never spent too much time talking about the particulars, we never had those curiosities as we were growing up. We just knew that if any fish around, he going see them, and he going know what kind, period.” “I know Kalani always used to come get him, if he see from Lumahai. Then, after they’d see ‘em then they’d say, “Yeah, but what if that’s akule?” So they end up, they go surround anyway. Cause they so worried about, “what if that’s akule?” The other guy get lucky, eh? So they surround them, that ‘ō‘io bust the hell out of their net.” “We caught the ‘ō‘io too, but I don’t know what it brought for a price. I would think, akule would be better. I’d rather eat akule than eat ‘ō‘io. Of course, there’s guys what like ‘ō‘io. But I think the only thing good about ‘ō‘io that I know is, to make fish cake out of it.” “No more tide charts those days. Had moon. Jerry had the tide, all moon, that’s his tide chart. Jerry, he liked early morning. My Dad, I used to go with him in the evenings. Sleep on the sand. My old man, he no like nobody around him when he go. He was so particular, he no like nobody move and scare the fish. He go out there, the fish gonna come all around him, he wait till they bunch up, throw his net. He don’t believe in making mistake, eh? He no chance nothing. Because nobody got that kind patience, eh? And he know the fish coming. So he going over there, going to establish himself, and he can wait for the fish eat around him, and wait for them ball up right for his net. “When he and my mother go, they come home, da kine 30 or 40 wen huli. No more wanna carry the bag, eh? And you can hear in the night they scaling, you can hear the scaler: shuck shuck shuck! We didn’t have to do nothing. “You going at night, you only going to see the tail, eh? You might not see how big the tail. So to be safe, when small kind running, nobody go throw the net. Easy to catch fish in the night. You sneak up, you know there’s white water, just go and wait till that thing comes to feed, the tail or fin penetrate the surface, easy, very easy.” “We never did go outside fish, only Kohe because we got taro patch. Mullet in that area, Kohe is all mullet area. And only in front of the house, at Poliaka, because the squid’s down there. We never had to go no place else. Every area different, so if you don’t fish in that area, you don’t know the style of the fish. If you don’t know the place, you never get nothing. At our place, in the front, after somebody went through, the fish going to be right back. And nobody know that, see? No place else to feed, that’s why. Get reef, well, that’s not feeding area. You gotta go feeding area, where you got the right limu. “My old man, he told us, ‘Never throw blind.’ As long as you can look, you can see.’ A lot of guys, they go right to the hole, they just throw the net. Then one day he told us, ‘As long as I live, I better not see you guys gilling fish or throwing blind.” (i.e. using gill net for surround). “In my time had plenty baby fish,” Uncle Tom exclaims. “Plenty: moili, male, ahole, all along the shore, every place where you get stream running, the fish breeding inside there. Along the shore you will see schools of them, piles of them, the small mullet, male and all that, moi too. Because we used to catch them and eat them, that time. And I’d rather eat the small fish than the big fish, it is more ono. Like the moili, you deep fry that thing, eat the whole thing. Like to ‘oama, same thing: eat the whole thing! That’s how we learn. “I get the best fish, the moi. The biggest moi I catch, ten pounds, ten plus. That’s the reason why I said, I learned the name all these places. I’m a moi fisherman, but I catch anything that’s out there. But the moi was the one, because at that time not anybody could catch the moi, because only the king ate the moi. It’s the king’s sister, the moi. Because the rule says that if you ever get caught, the penalty is death. That’s what it is. You go fool around that kine stuff when they put one penalty on, the penalty is death. No getting away. Somebody squeal on you, you’re dead. That’s how it was. More strict. And like everything that happens around you, if its strict, if the law is strict, you’re going to be scared to do that, because you’re going to get penalized. “Normally I don’t care for eat moi, I give them away. I’d rather eat the small one, the medium-sized moi. You can deep fry or you can dry it and pulehu, or fry or whatever. You can steam them, you steam is good, that’s what the Chinese like, that’s their favorite fish, the moi. So we used to go sell them, when we were young, for get pocket money.” “We always went daytime for moi,” Samson says, “when you can see them, outside Koi‘a. Moi, we catch them all outside the breakers. We passed moi season already, but usually, Hanakapiai, from April, second week, the buggers used to run.” Reef Fishing: Uncle Tom says that “At the time my dad was the best throw net fisherman. Like the old man La‘a [Samson’s Father] he used to go fish but he no can swim. If the sea knock him down, the wave knock him down he’s jam up already. That’s why Aunty Rachel used to go fish with him. In case he fall down she can grab him. That’s how before. La‘a he go fishing but Rachel got to be with him. Rachel was always with him, you know. Every where he went go fish, even go ku‘u like that, she was the boss. Yes, that’s how it was.” “In rock fishing, he never did fish any time,” Samson remarks. “He like to go rising tide, or after rising tide, and this time of fishing is maybe ten to twelve o’clock in the night, and that’s his favorite hour. He never care for the morning hour. But from ten to midnight, maybe to early morning about till one o’clock, if the tide was good, those times, that’s the best time for him. Throw net. A lotta patience. Usually he check up, like go on top, if he wanted to fish certain area, he would try it, low tide, walk on all the areas that are the known feeding areas. And he look for telltale signs of fish feeding. Like the growth of the limu: if cut, if bite, you know something feeding. If they’re eating that, and he want them, rising tide he’ll be there, wait for that. They going to be rushing for eat, yeah? He get em wired, no more guess work. Tide and time, that’s the main thing about fishing.” “Grandma Rachel was also known for catching fish with her hands, under the reef,” Lahela points out. “What hands to put where, where to grab underneath for certain type of fish. I think it’s the pi‘aia, I think it’s the small manini. I used to eat it when I was young. The small one, but eat the whole thing. You make a sauce, and eat guts, everything. Pi‘aia.” “Even during winter month, on the flat by our place, manini,” Samson adds. “Few guys can catch fish during the winter, but manini, she get ‘em. Where the surf strong, all that kind small fish gotta hide, they gotta stay in their house, stay underneath the rock. She always go in with a flour bag, just get two, one for plug the back door, and the rest, they stay inside, he just grab em and put em in the bag. But you gotta do that when the surf strong—the fish going stay in. They not going look for place to run away, for the current too strong for them to stay out. They gotta hide. But I look at that, even the surf too strong for me! My mother, she used to go right in the surf and pick em up. That’s her skill, She crazy for do thing like that, but it seems like that’s her skill. Good foot and good leverage.” Uncle Tom remembers spear fishing. There was an old practice of creating “imu” in the sea. Uncle Tom explains: “Like most times they go set up imu, down Koie, get plenty round stone. They go make imu and then the house, the fish go inside there you go look get plenty manini inside there. That’s all you do, surround that thing with your net and take the stone all out, and go build outside of that now, the same stone. You catch whatever fish stay there, if get anything, you going catch ‘em. That’s how the imu is. Well, maybe once in my lifetime I seen that. But this is the old times now. The fish just go inside stay inside there. They make big ones small ones, and all what they need to do for catch the fish, you go surround with your net, whatever they had. By the time you take all these fish, you get enough to eat already.” Sharing the Catch: “With the nets in old days,” Kawika explains, “when the fish would come in, the fisherman would surround the fish, and put the call out to the community, ‘Okay we’re going to hold these fish three days and you want fish, come and get them.’ So people come down and load up fish and at the end of the third day they open up the net and everything would go back out. And that’s how you maintain a sustainable fishery, you don’t decimate the whole thing, you just invite people to take what they need and then there is more for later on.” “At the time I used share the fish with all the kūpuna,” says Uncle Tom. I would get the car, I would give them away to the kūpuna all in this area, because most of kūpuna and their children were kind of moloā, I would say. Lazy.” “When make māhele, like La‘a [Samson’s father], his style is he going kiloi all the fish, catch the fish surround everything, puni, he go home. He no hang already. Rachel is the one take care and give the māhele and everything, that’s how it was. It’s not like the old man Hanohano and Kila, the old man Hanohano and the old man Tai Hook. They stay over there and give the people the māhele, whatevers. They supervise everything you know, and make sure the people go home with something for the labor. Because that’s the cheapest labor you can every get you know. And give the māhele, no need pay. The people used to rather take the fish than the money.” “My Dad, he was a commercial fisherman too,” Samson adds, “right down by the park. That’s where we fished. Big, deep, heavy nets. Big boat with two guys got to row. Two guys throw the net. Then always get breaking wave right in that corner, right by the reef. Always had waves there. They always tell us, “Don’t worry, that’s my job.” So in other words, he just had it. His part was, everything left in the net is for everybody and he made sure everybody had full share. Always look at that. Even other fisherman said, ‘Ah, too much.’ My Dad? No, he’s got his plan, being out there in the group. He’s not going to worry about liar, he just don’t pay attention. He’s one of a kind. He’s got his plans, doesn’t let nobody touch his net for sew. He do it all himself.”

|

|

|||||||

|

"The idea is catch them," Samson explains, leaving us with one last thought, “no worry about get rid. Easy for get rid. You drop the next house. If you get too much, dump 'em. Whoever pass him, take ‘em. Too much is no problem, because you always got your neighbors, eh? Everybody get too much, the always dump them, even to today. The guy who catch plenty, easy for dump, a lot of guys come around. Plenty guys like fish, but they no like do nothing, eh?”

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

| Copyright 2018 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||