|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

"The ruling families of Kaua‘i were the highest tapu chiefs in the group," wrote Abraham Fornander in 1878. This is "evident from the avidity with which chiefs and chiefesses of the other islands sought alliances with them. They were always considered as the purest 'blue blood' of the Hawaiian aristocracy..." In 1796, Kamehameha—on his campaign to unite the islands—made his first atttempt to conquer Kaua‘i, but was forced back by storms and rough seas. He made a second attempt in 1804, but an epidemic called ma‘i ‘ōku‘u (possibly typhoid or dystentery) swept O‘ahu and killed thousands. Kamehameha himself was taken ill but survived, but his forces were depleted. In 1810, Kaua‘i's ruling chief Kaumuali‘i ceded control of Kaua‘i and Ni‘ihau to Kamehameha. "Kamehameha I and Kaumuali‘i had arranged a truce in 1810,” Andy says, “so that Kamehameha and his army wouldn't invade Kaua‘i. As part of the negotiations, Kaumuali‘i said to Kamehameha, ‘You can have my lands.’ By offering his lands—the island of Kaua‘i—Kaumuali‘i was offering to give up his sovereignty. Kamehameha replied, ‘Keep your lands. They are for my son.’ In other words, Kamehameha was allowing Kaumuali‘i to remain king until his death, then the lands would go to Liholiho." The 1824 war finalized the Kamehameha rule on Kaua‘i “From that point on, it is Big Island chiefs loyal to the Kamehamehas who are appointed here as governors, and they rule Kaua‘i right up until the end of the 19th century. And—my opinion again—they don’t really rule. It depends. The first one or two maybe do. Ka-iki-o-‘ewa probably does rule; he was a high ranking chief under Kamehameha the Great, and an active governor. But after that it’s mostly the haoles who run the island. It takes a while for the haoles to purchase the land, but over time the haoles replace the Hawaiians as the decision makers. Although there are people who are called ‘Governor of Kaua‘i,’ I can’t find what they do. “These would be the plantation people. Missionaries were influential early on, but by the middle of the century it was the plantation owners. The Robinsons on the west side, the Rice’s in Līhu‘e area. Actually the last governor of Kaua‘i was a Rice. The very last one, only for a year or two. It’s 1892 or ’93, something like that. “The westerners were bringing in the cattle, the cows—which a kapu was put on immediately—and the goats and so forth,” Kawika explains. “It’s a kind of transition between the traditional system into capitalism and this huge flux of change all happening at once, coupled with a breakdown of the ali‘i system and the influence of foreigners on the political system and slow erosion of power and tradition, all of that happening at once.

“In a traditional context, if these things were brought in slowly and given kind of a generational chance to see how they work and see how you could tweak things out, that was never allowed to happen. It was just, here’s everything all at once and at the same time. The power structure was breaking down—the kapu system was broken in 1819, and the kapu system was what really controlled everything. Once that was gone, it was like a free-for-all. All the power-hungry ali‘i were getting sandalwood out of the mountains and all this stuff was happening and the kapu system, which for about 1,000 years had been keeping things in check, that was no longer around. “And so even if resource managers and the people of the lands, or the kūpuna saw these changes happening, they were almost powerless to do anything because what had been the vehicle for curbing these things had been abolished and been replaced by a system that said, ‘Yeah, this is what we want.’ And so that was the 1800’s in a nutshell. A lot of things happened and we’ve learned a lot from that, but how do we adjust? I think we are now, but we’re still doing so in the absence of the kapu system, which is challenging for people who really liked how that system worked."

|

|

||

|

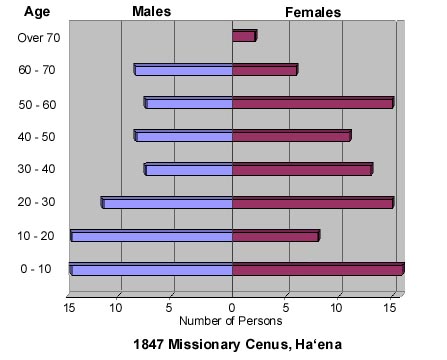

Two census counts taken by missionaries are presented below.

1835 Census, Hā‘ena, Kaua‘i

Source: Schmitt 1973: 26 1847 Census, Hā‘ena, Kaua‘i

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A look at the figures described in the 1847 Census shows a healthy and growing population. These numbers, arranged in a population pyramid (below), show a distribution characteristic of growth: their are a good number of children and young people given the adult population. This is significant because of the negative impact of introduced diseases during the first few decades of the 19th century, and the drop in fertility that resulted. Hā‘ena at this time, however, appears to be healthy, and has a larger population in 1847 than it did in 1835.

|

|

|

It is said that Hā‘ena was always ruled by a woman. How far back this tradition goes and who these chiefesses were is not certain. But at the beginning of the 19th century, of two major figures in leadership at Hā‘ena, one of them is the chiefess, Kekela-a-ka-lani-wahi-kapa‘a. Kekela was the konohiki who managed the ahupua‘a under ali‘i Abner Paki. She was also the sister of Abner Paki's mother, and the sister-in-law of Kamehameha. During Kamehameha's conquest of the Hawaiian Islands, Kaumuali‘i—the ruling chief of Kaua‘i—had sent his nephew Kamaholelani as an emissary to Kamehameha's court to discuss a truce. Kamehameha presented the recently widowed Kekela to Kamaholelani as a wife. Kekela returned to Kaua‘i and with Kamaholelani, settled at Lumaha‘i, two ahupua‘a down from Hā‘ena, and which had been given to them by Kaumuali‘i. Kamaholelani passed away in 1820, and in a brief civil strife in 1824, land on Kaua‘i was redistributed to chiefs from O‘ahu and Maui. Kekela returned to O‘ahu, probably having lost her land, but in 1837 was appointed as konohiki of Hā‘ena. It is said that in the Mahele, she encouraged commoners to file land claims, resulting in a higher density of kuleana land tracts than found in other areas. Her story is linked with the chief of the time, Abner Paki. Abner Paki was a prominent ali‘i. The father of Bernice Pauahi Bishop—after whom the Bishop Museum is named—was guardian of Lydia Kamakaeha, who would become Hawai‘i's last monarch, Queen Lili‘uokalani. Carol Silva describes as Paki as "a chief of the old tradition. He resisted Christianizing and together with Liliha (widow of Oahu governor Boki and guardian of Kamehameha III) were seen as the last remaining vestiges of the old native order. Paki had considerable political and economic responsibilities; he was placed in command of sandalwood expeditions on Oahu...and was later given charge of the Fort and its supporting lands of Punchbowl and Waikiki. Furthermore, in three days he rallied several hundred men to construct the tremendous Nu‘uanu irrigation system which supplies the numerous taro pondfields begun by Kamehameha in this valley after the battle of Nu‘uanu. This irrigation system is known even today as Paki auwai.... "Paki understood traditional management of water and land resources and would encourage enhancement of these resources for higher crop yields. Not only did he possess an excellent working knowledge of land and water systems, but he was charismatic and firm in his execution of such improvements" (Silva 1995: 27).

|

|

|

In the ensuing pages, we shall see how the arrival of "visitors" from the West introduces numerous changes to the entire Hawaiian system. These changes start with the arrival of Explorers.

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

| Copyright 2018 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||