|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Just prior to and during legislation known as the Māhele (1848) and the Kuleana Act (1850) was the period of history when traditional customs and practices of the Hawaiian nation were codified into law,” Carlos explains. “In the new laws and newly drafted Constitution, Kamehameha III, executive head of the Hawaiian nation, attempted to protect and preserve in the institution of the judiciary the life ways that had served the Hawaiian people well for many hundreds of years. “Definitions of fishery boundaries were among many traditional practices and perspectives codified in the laws. At the same time, new concepts of private property introduced by the foreigners (missionaries and other advisors) were also incorporated into the body of laws enacted during this period when the fledgling Hawaiian nation came into being. “The Māhele of 1848 and the Kuleana Act of 1850 were two of the most important pieces of legislation marking the change from traditional, communal use of ‘āina to ownership of land as private property. After debating land issues for almost two years, the mō‘ī and ali‘i accepted a plan drafted by Justice William Lee. The mō‘ī would retain his private lands ‘subject only to the rights of the tenants.’ The rest of the land would be divided into thirds: one-third to the Hawaiian government, one-third to the ali‘i (konohiki), and one-third to the maka‘āinana, ‘the actual possessors and cultivators of the soil.’

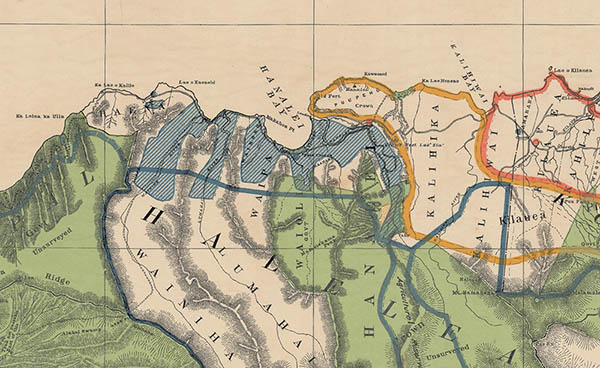

“Kamehameha recognized that a little bit of land, even with allodial title, would be of very little value if the owners were cut off from all other means of producing a livelihood. “During this phase of privatization of the land, maka‘āinana had to register claims if they wanted to legally own land they had been occupying for generations. However, due to a variety of factors, relatively few maka‘āinana submitted claims and even fewer were awarded lands. As a result, far less than one percent of the land in Hawai‘i was awarded to the people who actually worked the land.” Several reasons given by historians and observers of the time as to why this happened. In part, “maka‘āinana, especially those in the outlying districts away from the port towns, had very limited access to cash. They could ill afford the survey fees required for submitting and receiving awards of land. Most important, however, was the fear that by taking an award, maka‘āinana might be limiting their own access to the waiwai (resources) of the ahupua‘a. It is entirely plausible that some maka‘āinana assumed that if they did not act to change anything, the traditional system would simply continue. Also, there is some evidence to support the possibility that those living under less than honorable konohiki were compelled not to file claims or feared reprisals if they filed a claim. “The Māhele and the Kuleana Act also forever altered the traditional relationships between mō‘ī, ali‘i, and maka‘āinana. The mō‘ī, once connected by genealogy to akua, became an abstraction called the ‘crown,’ a secular entity. Ali‘i, once expected to be kind, generous, and beloved leaders, were transformed into landlords, and ‘āina—elder sibling—now seen through the eyes of the surveyor's glassy-eyed instrument and articulated in roods, rods, chains and acres, was no longer recognizable if not actually cultivated or built upon. “Hā‘ena was awarded to Abner Pākī, a powerful ali‘i closely allied with the Kamehameha family. Like most lands granted to ali‘i, this award was subject to the rights of the maka‘āinana. Pākī was the grandson of the former Maui mō‘ī, Kamehamehanui, who was the brother of Kahekili, the great Maui ali‘inui. Pākī was married to the ali‘i wahine (female ali‘i) Konia, a daughter of the Kamehameha clan. Their child, Bernice Pauahi Bishop, would receive many lands from dying, childless ali‘i in the coming years. Eventually, these lands would comprise a massive estate she left to establish the Kamehameha Schools, a school for Native children. “Letters from Pākī to the Department of Interior illustrate how Native perceptions and practices regarding land continued during this time of transition. In one of these proclamations, Pākī announced to the populace and the government that as konohiki he had reserved (ho‘omalu) the he‘e (octopus) as his protected ‘fish’ within the fishery attached to the ahupua‘a of Hā‘ena. In other ahupua‘a on Kaua‘i awarded to him, he reserved ‘uhu (parrotfish-Lumaha‘i ahupua’a in Halele‘a) and akule (big-eyed scad—Wailua ahupua‘a, moku of Puna). By documenting these protected fish in writing, Pākī, ali‘i, proclaimed his traditional role as head administrator of the ahupua‘a even under the new system of law. “As was the custom of ali‘i with widespread estates, konohiki were appointed to care for the resources found in outlying ahupua‘a and ensure that the activities of the maka‘āinana ran smoothly. Kekela, a close relative of Pākī, was appointed by him as konohiki of Hā‘ena in 1837. Kekela registered, at the time of the Kuleana Act of 1850, a claim as konohiki having authority over kō‘ele. Kō‘ele were lo‘i traditionally cared for and cultivated by the maka‘āinana but whose produce was reserved for the ali‘i of the ahupua‘a. Kekela is one of several female konohiki claiming and being awarded land. Though women were rarely awarded land, in Hā‘ena a few widows and female heirs of longtime residents did apply for land. Perhaps Kekela’s presence as konohiki of Hā‘ena encouraged a higher than usual number of women to file their claims."

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

Haole |

Kukukaelele |

Nahialaa |

|

|

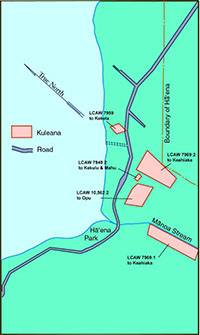

Click here to see a complete listing of Māhele claims for Hā‘ena. |

|

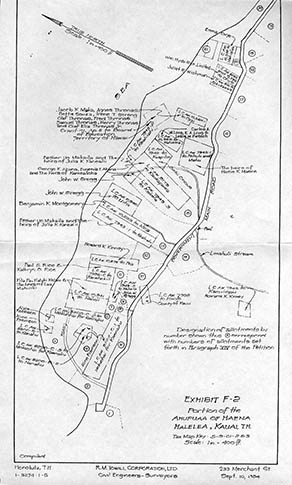

||

|

“Out of the twenty-one Land Commission Awards granted in Hā‘ena, fourteen awards were for single parcels of land. In many other areas of Kaua‘i, claimants generally received two parcels—a house lot and a parcel of land for cultivating taro. Only five of the Hā‘ena awards contained two parcels; two claimants were awarded three parcels. It seems that in some cases, house sites were located close enough to the lo‘i that it was more practical to include both in one parcel of land.” “Eight of the 23 had received their lands directly,” Carol writes, “three had inherited their parcels from their fathers, one from his grandmother. Six claimants were registering parcels that had come to them as a result of marriage (ie. a widow of a tenant remarried and her new husband registered her claim under his name or a widow and child laid claim themselves).... “Hā‘ena thus sustained a majority of its original tenants from Kaumuali‘i’s time and the residential and agricultural patterns were largely preserved during Kekela’s management.” Carol suggests that due to Kekela’s long association with the neighboring ahupua‘a of Lumahai, she would have been familiar with the older Hā‘ena residents, and could not easily dispossess them, especially if they were good productive keepers of the land and respectful of her office."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

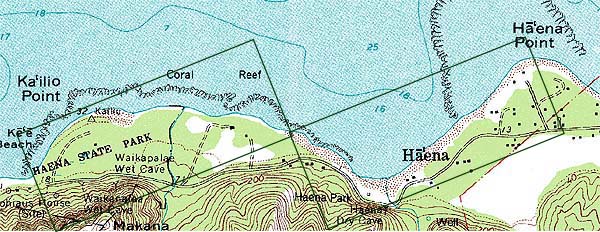

Kuleana lands were mostly on the makai or ocean side of the ahupua‘a, in the lowland agricultural zone. The following map, in two parts along the shoreline zone, show the Land Commission Awards (LCAW) from the Māhele and identify the recipients. Parcel sizes, in the Hawaiian language documents (and the notes were written in Hawaiian well into the 20th century) were in acres (written as "eka"). Other forms of land measurement used included "rods," "roods," and "chains." “In order to receive an award of land under the Kuleana Act,” Carlos continues, “maka‘āinana were required to submit a written claim and have two witnesses verify their claim. Each claimant needed to identify how he or she came to live on the land claimed. According to the testimony recorded at the time, some of the lands awarded to maka‘āinana had been held since ancient times. "While Kaumuali‘i is mentioned as grantor of the land to six claimants in Hā‘ena, other claimants simply said the land had been given to them by konohiki from ancient times without mentioning a specific name. Several konohiki names—Kalaniulumoku, Kamokusohai, Kaikioewa, and Kamo‘opohaku—are mentioned in the testimony. Of course, Kekela, as the one holding the position during this critical time in the history of Hā‘ena, played an important role in granting land to maka‘āinana. “Taxation not only coerced people into earning cash, it undermined the traditional relationships ali‘i and maka‘āinana had enjoyed over centuries. Traditional checks and balances in the ahupua‘a serving to curb abuses of power and promote relatively egalitarian relationships between ali‘i and maka‘āinana were displaced by foreign concepts of law necessitating judges, lawyers, and legal paraphernalia. The imposed market economy and Euro-American systems of jurisprudence/land tenure in which the Native people were now enmeshed would unravel and erode traditional familial relationships they enjoyed with the land, its creatures, and each other.

“Many maka‘āinana, especially those not granted land, also left their ahupua‘a in post-Māhele times. Often they settled in towns or near seaports where cash, almost entirely derived from foreign sources, was more available. The need to access sources of cash was a major reason people left the ahupua‘a. They could no longer pay their debts and taxes with products of subsistence life ways or satisfy their obligations to society through contributions of shared labor, as they had in the traditional system. “By drawing artificial boundaries, the division of the land under the Māhele and Kuleana Act began a process that restricted the ability of maka‘āinana to access and sustain themselves through resources within the ahupua‘a. Maka‘āinana were even more constrained when ownership of ahupua‘a came into the hands of foreigners, which happened in a large majority of cases. “Although many ahupua‘a were sold to haole (foreigners), a significant number (Watson 1932: 9) were sold to groups of maka‘āinana who organized hui kū‘ai ‘āina (cooperatives to buy land) as a means to raise the cash necessary to purchase lands being offered for sale. In some cases, ali‘i owners of ahupua‘a offered the first chance to buy these lands to the maka‘āinana residents. Not particularly suited for commercial use or sugar cultivation, Hā‘ena probably seemed like the end of the world to those who dwelt in the burgeoning new city of Honolulu, where Pākī, his daughter Pauahi, and his son-in-law Charles Reed Bishop lived.

“When they had the Great Māhele, that’s where I read that maka‘āinana thing,” Uncle Tom says. “The Great Māhele they were the last people that was looking – they were starting to sell our land, when they had the Great Māhele. All of that came about that time. Because they were kind of careful already, like the men, they was giving it away. So they kind of hold what they had. Because by the time, you know, most of the properties were gone. How all this thing wen happened is the Americans went do that. The people that came as missionaries—but they weren’t really missionaries when you come and look at the whole picture. They came over here and tried to create all the rules and stuff, and made their own rules—that’s what happened, you know. “And then pretty soon by that time most of the land was gone, and they became powerful, these haole people, the first people that came. They came all as missionaries, get plenty, like the Robinsons, the Rice’s, the Wilcox’s, and Kōloa was these other people. There owned a mess of land over there, these people. I know the old ones before they used to come. Eric Knudsen, they were all the people. “And then they had these other people, the Big Five, them the one go plant this damn thing. That land over there was over here—the land was Titcombe’s. Titcombe was a big name before. They used to own a lot of land up in Wainiha, behind Hanalei schools, Hanalei plantation, Kilauea plantation. That’s why their family grave all in by Kilauea school, because they owned that whole land. But how did they lose them, I don’t know.” “In Hā‘ena, the situation evolved in a slightly different way than happened elsewhere,” Carlos points out. “Here, Native Hawaiians, by pooling their resources, were successful in acquiring ownership and most of the control over land considerably longer than in other areas. “Kamehameha III believed that, by recording titles, Hawaiians could forever secure their ‘āina. What he did not foresee was that these foreigners, whose ideas of the land did not include preserving forever the basic needs of the Hawaiian way of life, would eventually take his country from the people. These foreigners saw land as the means to increase their fortunes and to solidify their place in the islands. They set about replacing the Hawaiian worldview with a vision imported from continental America and Europe.”

|

|

|

|

While many residents across the islands whose applications to receive kuleana lands were not successful, a special development occurred in Hā‘ena that allowed them to remain in residence, using the land. The aftermath of the Māhele produced a special situation in Hā‘ena.

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

| Copyright 2018 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||