|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Wind is an interesting phenomenon because you don’t actually see wind, you feel it," Ben muses. "It’s trial and error, knowledge through experience leading to understanding of the wind, and it becomes a cultural practice. “In the northern dialect, we use both yang and habweil to say ‘wind’,” Yoane explains. “But when it’s strong wind, then its malamál. Then it becomes a typhoon!”

|

||

|

|

||

“Afil yang is the cool wind,” says Joaquina, “you know there’s the wind that’s blowing, and then sometimes in the evening there’s a cool wind that blows, or early in the morning, or sometimes even in the afternoon there’s a cool wind that is blowing. That is afil yang. When there is typhoon and it is not very strong, we say that it’s ‘banana typhoon’ because only the bananas fall over, not the house.” “It’s what they call a tropical depression,” Cathy adds. “Everybody knows that when they say ‘tropical depression’ it’s a ‘banana wind,’ it’s not one that’s a typhoon already. But the navigators, they have their own words for wind that we women don’t know about.” "There are a lot of typhoon warnings" Ben explains, "but that does not necessarily mean we get hit by the typhoon every year. Almost every year we have maybe up to ten typhoon warnings, and some of them end up becoming super typhoons, meaning they have winds beyond 150 miles per hour."

|

|

|

"Typhoon Ponsana that recently hit Guam and Rota went about 170 miles per hour. The devastation is huge, a tremendous disaster. We were spared that time; Saipan had hardly any damage. But back in 1983, maybe ’86, Super-typhoon Kim hit us here. A lot of trees went down. "Some of the mango trees are very strong and deep-rooted, and so they withstood the typhoon, but there were no leaves on any of these trees here. They were all denuded by the strong winds. Coconut trees are hardy trees. They’re also deep-rooted, and so they withstand a lot of these typhoons. A lot of their fronds get broken off, but then they regenerate again. That’s the beauty about coconuts. They regenerate fast and are able to produce young coconuts, and we have to go and use them for drinking water."

|

“People way back in the time when I was young, they knew how to read the movement of the wind and the movement of the skies,” Dave says. “If they looked up at the skies, they could easily distinguish whether the typhoon is coming. Another thing we knew from the old times: we looked up at the sky and when we saw certain birds flying on the skies, that’s when we learned that there’s a typhoon coming. And then we could prepare for it. “We didn’t have a radio at that time, so we usually had to be prepared and search for a shelter. At that time, we needed to get ourselves into the cave and hide there for shelter from the typhoon. We didn’t have concrete houses like we do now for permanent shelter for those people that are going to be in danger from the typhoon. There were people that found it easier to go to the church for shelter, but other people stayed close to the cave. They had to evacuate themselves to the nearest cave."

|

|

|

|

|

|

“I was in the cave during Super-typhoon Jean. In the cave we had to be prepared. We had to come in with something to cook on, the pots, the wood, the dry wood and everything. We started a fire and we did our cooking there, and we also had to bring in water. We couldn’t find batteries so we had to search for candles."

|

||

|

|

||

“I was sixteen-years-old,” Dan remembers. “At 11:00 o’clock in the morning my father told me to go to the village and buy cigarettes for him. I was not paying attention, so I took the money to buy my father cigarettes, but when I reached the village I played with my friends. So by around 12:30, the typhoon was blowing hard. I ran to the store, which had almost closed. I ran to the store and I bought my father a pack of cigarettes. "Then by almost 12:45, the wind was blowing really hard, a very strong wind. But I managed to reach the farm. When I got here my father was maybe a little bit mad at me, but maybe he thought that the typhoon was really hitting the farm already so he forgot about his anger and said, ‘Where’s my pack of cigarettes?’ I gave it to him. He said, ‘Okay, you take the water and the pots and go up to the cave'."

|

|

|

“I took those things up, and returned back to get more things: the dishes, our clothes, and rice and some candles. Then our neighbors were running in. I told them that I already put water up at the cave. This one family with, I think, seven of them, they came, because they knew the shelter is up here. It was quite far for them to bring their stuff and food, clothes and things like that. So I told them that I already brought some water, food and candles up there. "My dad was up there already and they started looking to move to the shelter, so I guided them up to the cave, carrying all this stuff, and two of their sons, maybe twelve and thirteen years old, helped me carry some stuff from here. We didn’t take the stuff from our house because there was already a strong wind, and the roofing tins were already flying. But we managed to collect what we needed, and then we got up to the cave."

|

|

|

|

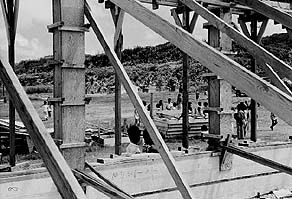

The cave shelter above Dan's house.

|

“When we reached the cave, that’s when the typhoon got really, really worse. Then when everybody was in the cave, the old people, they liked to smoke. My father, my auntie, my uncle, they all smoked in the cave. And when they smoked it was like pollution inside, and we didn’t like the odors in the cave. "So I went in there and I stole three cigarette from my father’s pack. I went outside close to the main entrance to the cave and I smoked there. It was very cold, I got all wet because of the rain. "After that, I took my stuff and went inside to sleep. It was very hot in the cave. Even the families who shared the cave, they were also very hot. So they had to come out little by little to feel the breeze, just a little bit of wind or something. We slept together in the cave. We just put our mats down and we slept together."

|

||

|

|

||

|

“We weren’t able to block the opening of the cave,” Dave explains “because it’s a wide door, a wide area, so what we did was we sought the inner part of the cave where the wind can not get itself in. So when the winds came we were safe in the back of the cave. While the typhoon continued, we had to be inside the cave. And whatever we had in the cave, whatever food we had, we shared. We shared the water too.” “We stayed one week in the cave after the typhoon,” Dan continues. “Then we came down here to the farm. We tried to build a small house so we could have shelter here, rather than going back up to the cave. We built that in maybe two weeks. We helped also to rebuild the other houses so the family could go back and stay."

|

"We had a lot of assistance from the States. They provided every village with rations: corned beef, or tuna. They gave us rice. They give us a can of chicken. They gave us a can of luncheon meat. Mostly canned food. And milk, cheese, honey, flour so we could cook our own food. They call it haikyu, it’s something like food stamps. “For water while we were living in the cave, I always came and refilled from our rain water tank here. There was no problem with the water because we have the water collection. It’s rain water and you have a lot of rain before the typhoon and after the typhoon is here. I had to come down here while we’re in the caves, three times a day. Five gallons in the morning, five gallons in the afternoon, five gallons in the evening. That was my job.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

“I remember Super Typhoon Jean to be one of the strongest typhoons on the island,” Dave points out, “and I recall that many houses were destroyed. That was one of the strongest typhoons, and it brought colossal calamity to the island: destroying all the houses, damaging all the trees. "The people, at that time, were not provided with rations, so what they did was they tried to get back to the original resources that they found very important and necessary for them to survive. Like the taro. That’s part of the culture that we used to live on. We tended to the farming, planting the crops that were needed for our consumption."

|

||

|

|

||

“When the typhoon was gone, everybody went out and went back to their properties. I remember we had to carry our possessions back to our place. We took all our valuables. When we got back, the typhoon had brought us a good portion of calamity, so we had to start finding a way of rebuilding our house first, that’s the first thing that we needed to do. Build up the house, and it doesn’t have to be a very nice house as long as it gives us shelter. "We can build a house, a temporary house, we call it a sade’guani (typhoon shelter). It’s sort of a hut. We utilized that as one of our houses."

|

|

|

“During Typhoon Jean, our house was broken down,” Estella recalls. “Only the floor was left of our house. Everything inside we found in the middle of the ocean, down at the beach. Our ice box, our water tank. During Typhoon Jean, the ocean came all the way up to the road down there. All the way to the church. People were sheltered in the church. "And when we came back, our house was gone, nothing, only that pole, the foundation. It was a wooden house back then. And then later on they found the trunk of my wedding things down at the river. So they picked it up and brought back. When I looked in it, my wedding gown and my afternoon dress, and all of my certificates and the pictures inside, they were all gone.”

|

|

|

|

“We had to collect those broken things that were blown about by the typhoon,” Dave continues, “and put them back together, and then we’d come up with a decent house. I saw during those times that we needed to help each other. If you wanted a house to be built up right there, you had to be helping one another. It’s a community system. Right now we can see that when there’s a typhoon, there’s a Federal system that comes in, so it is very different to compare today and before.”

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanapag Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||