|

|

|

December 28, 2016

Heading out from St. Michael's, Maryland. It’s taken a long time to reach this point in my story, but the canoe was actually finished by the fall of 2013—about four months after I started. That August, I took the canoe and my son (then almost 4) up to visit my cousin Allison and her husband Steve in New Hampshire, and they took us up to his family’s place on Little Sunapee Lake. This was my first opportunity to actually launch the canoe. My first notion was to try it just as a paddling canoe. The Melanesia can be built as either a paddling canoe, or as a sailing and paddling canoe, which is what I did. So I put it together without rigging the sail. I mounted the ‘iako and the ama, as well as the bamboo set-outs. I am including the first photo below to show that my cousin and I were easily able to life and carry the canoe to the water. Even when loaded, two people can move this canoe pretty easily, though it helps to have a sandy beach where you can drag or shove it yourself if you are going alone.

Out I went, and the very first thing that I noticed was how incredibly stable the canoe is! There is no comparison to your ordinary tippy lake canoe. The outrigger turns this into something more like a catamaran in terms of balance. The width of the platform created between the outrigger and the hull makes this a very stable craft. I paddled out, then came back and picked up my son. Now you can see, once both of us are in the craft (he being much lighter than I am) that the stern of the canoe is pretty close to the waterline. This had been my concern as soon as I looked at the plans and the images on the Wharram website, and will lead me to ultimately modify the canoe. But that’s another post. Then we put the sail up. Oh my goodness! The craft is light, the wind was moderate but sure, and away we went, smooth as silk. I had some difficulty figuring how to simultaneously hold the sheet and steer the canoe (hence my later addition of the cam cleat), but it was miraculous to actually be sailing in a boat I had built myself—and, just a reminder, I had no previous boat-building experience. Not even that much carpentry.

With time I got my system down and could put the canoe together efficiently in 30-40 minutes. Taking it apart is even faster. As I mentioned earlier, the entire craft—dismantled—fits on top of my VW golf. In half an hour I can go from my home in Baltimore to Rocky Point on the Chesapeake Bay, assemble the canoe, sail for several hours, dismantle and load the canoe, and be back home, all in one afternoon.

This has changed my perception of living near a large body of water. I grew up in Washington, DC, not that far from the Chesapeake Bay, but had no sense of it’s presence at all. Now it is virtually my back yard.

Now I want to point out one more minor modification I did to the design. Wharram’s instructions leave the bow and stern compartments open. You are advised to maybe get a bunch of empty plastic bottles (with their lids on) and tuck them in there for floatation. Wharram also advises you try swamping the canoe in shallow water, just to know how it will behave. Well, I never did that, but I did worry about floatation. So i painstakingly sealed up the bow and stern areas, leaving a valve to let out any water that might get in. It was really difficult figuring the shapes of the pieces to cover these areas—lots of angles and curves—but I managed. This left me feeling much safer.

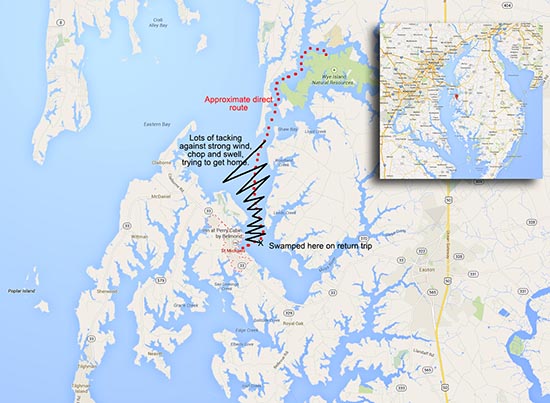

Then in October 2014, my then-girlfriend (now my wife) and I took the canoe to the Mid Atlantic Small Craft Festival (MASCF) in St. Michael’s, Maryland. I had attended this festival the previous year, when I was invited as keynote speaker (on the topic of traditional Oceanic navigation). The festival includes an optional overnight sail 9.5 miles up the Wye river to a charming campsite, and I had done that the previous year as well. I wanted to share the experience with this lovely girl. Unfortunately, the wind was dead against us going up, and we ended up getting a tow from the safety boat (which had also transported our camping gear to the site). The previous year I had paddled the entire way, as there was no wind at all, but that was too much to ask of a new partner. We spent a lovely night with the small group of others who had made the trip (they all had larger boats, and motors). The next day sailing back, the wind had shifted almost 180 degrees and we were again at a disadvantage. The crab-claw sail just does not like to sail into the wind, but is awesome in crosswinds or downwind. Anyway, it was a lovely, sunny day and we tacked a lot, making reasonable time but gradually falling behind everyone else.

Then we reached the one spot where we had to turn into the inlet where St. Michaels sits. Here we were open to the Chesapeake Bay itself, and the 10-12 knot winds had again shifted to—yes, once again—directly in front of us. The sky had darkened and the water was getting rough. My instincts told me this was serious and that I had to really pay attention. What we did not know was that a flood tide was now mixing with this strong and adverse winds. So we tacked back and forth, endlessly, each time loosing so much ground to leeway drift that we were making very slow progress going forward. But we were getting closer. The safety boat came back and told us he was going in for the evening. He asked us whether we wanted a tow. It was now about 6 pm, in October. We said no—we were so close! On one tack, we almost arrived at St. Michaels, so I decided on the next tack to go waaaaaay out, almost to the other side of the inlet, so that for sure we would reach our goal. “Prepare to tack,” I announced, and my girl bent over to avoid the swinging spar. I started to sweep with the steering paddle to turn the canoe, then glanced down. There was six inches of water in the boat! “BAIL!!!” I yelled frantically, and she scrambled for the bailer she had been using to manage the little bit of water we had been shipping all along. Then I turned and saw water wash over the stern of the canoe. “We’re going down!” I announced, as the water came up and the canoe sank beneath us. I felt it go down past my feet, and worried that it was truly sinking, but it gradually came back up, leaving a floating bathtub. The water was warm, thank goodness, and we had been wearing life jackets all along, but I had to scramble for our belongings that were floating away (the safety boat had transported all our camping gear, thank goodness). We tried the trick I had been taught in Micronesia: we stood on the ama in an attempt to angle the hull out of the water to empty it. But the hull did not have enough floatation for this to work, so we had to flag down a nearby catamaran (there were almost no boats on the water, as it was getting dark).

A surly young man with his partner and elderly parents begrudgingly rescued us with his expensive catamaran. Once we had piled our belongings on his deck, I said “Now if the three of us just lift the canoe by the booms, we can dump the water out." “Hey man,” he replied sternly, “I’m not here to save your boat." So I left the sail up to make it easier to spot, and watched as it receded into the distance as we motored away. The man got on the radio to the Coast Guard to let them know he had rescued us, and when the Coast Guard asked about our boat, he replied “It’s just a pile of sticks.” This is a man who had not built his own boat. We were unceremoniously dropped off a quarter mile from where we needed to be (but, where HE needed to be), carrying our wet gear and wet selves through the dark and wind and back to the festival. There, some friends we had met immediately swung into action, commandeered a speed boat, and we went out to get the canoe. These are people who had built their own boats. It was almost dark, but even with the dark sail, we were able to spot it. The canoe had drifted almost a mile back towards the bay. Then we did as I had suggested earlier: we lifted it by the booms (‘iako) and dumped the water out. Strapped it along side and took it back.

The next day, as I was giving a demonstration on traditional canoe building, a bunch of grey-bearded boat builders stood around my canoe, which was parked on the ground nearby. “I’d put a floor in it,” said one, “and extend those floatation tanks as far as possible." Yes, I thought. And raise the gunwales! I had always worried how close it was to the waterline, but the Wharram folks had discouraged me from tampering with the design. Now I am in the process of instigating these design changes, which I hope will make the craft safer and more seaworthy. Someday I will update this blog about that. But for now, I am signing off. This has been the Voyage of Building an Outrigger Canoe. It was something I had always wanted to do, but never thought I had what it took. I learned—and I hope you did too—that with just a little knowledge, a great deal of perseverance, and help from articles like this and from YouTube videos, anyone could do it. I encourage you to give it a try. There is nothing quite like setting sail in a craft you built yourself.

Aloha nui, —RDK Herman |

||

|

Copyright 2016, Pacific Worlds & Associates |