|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Areas | Seasons | Forest | Ocean | Sky | Language | Sources & Links | |||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

“We average about 80 to 100 inches of rain per year, because the majority of our rainfall is orographic rainfall. Here, because our cliffs are so close to the ocean, we're catching those clouds and condensing them and causing rain to fall. You look at Kapa‘a, which is directly windward, and yet it's very dry. And the difference is, you go to someplace like Maui on the wet windward side of Haleakala, because the mountain goes up so rapidly, you get Hana, Kipahulu, all those areas are very very wet areas.” The localized landscape also plays a role in catching the rain. A Hawaiian kupuna visiting Limahuli Gardens pointed this out one day. She was told that the name of the high peak to the back of the valley is Mauna-pulu-o. At Limahuli Gardens this name had always been understood to refer to the pointed shape of the mountain (mauna), comparing it to a scraper ('o) for pulu, a soft yellow wool derived from stalks of the hapu‘u tree-fern. But this elderly Hawaiian lady shook her head. "No," she said, "that's where you get your moisture--from that mountain, scraping the winds that come by. That mountain is the source of your moisture." Pulu has several meanings, and while one of them is the wool of the tree fern, another is "wet, moist, soaked, saturated." Multiple meanings are common for Hawaiian language and place names. It is very possible that both meanings were applied to this mountain. Winds: There is an episode in the story of Hi‘iakaikapoliopele in which the winds of Kaua‘i are named. Chippers says, "in this story, Pele comes out of the crowd, and she's so incredibly beautiful, and this young ali‘i asks her where she's from. And she says she's from Kaua‘i. And of course, he's the bull of Kaua‘i, he knows every good looking wahine on the island, and he says 'no way, I know all the chiefesses from Kaua‘i.' And she says, 'no, I am from Kaua‘i.' And to prove it, she begins in Anahola, and chants all the winds of the island. Now how can anybody know all of that if you weren't from here?" As the tale was recounted by Joseph M. Poepoe in 1911, Pele states, "He mau wahi makani hoakaaka ko Haena nei, a oia keia; e hoolohe mai oukou:

Drawing on work done by Mary Kawena Pukui as well as his own experience as a long-time resident of Hā‘ena, Uncle Bruce elaborated on these winds.

Other winds include:

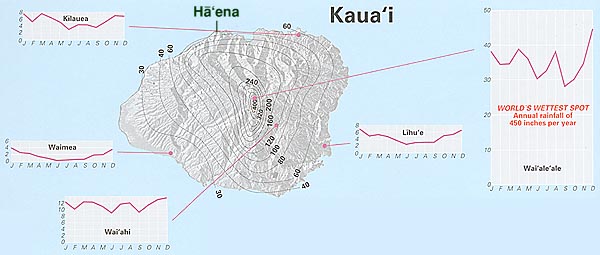

Other seasonal effects: “Because we live on the north side of the island,” Carlos says, “we get huge waves during the winter. Roughly between the end of September all the way until May there care big wave events. Every winter there are big waves at some point in time. And this winter being an El Niño year, we’ve had a succession of big surf. So their concerns are about where the fish move to during these events, whether it’s safe or not to go get them, and what is the best time of day to go get them. Reading the directional celestial signs, stars and planets, is not their concern, they don’t directly affect their present subsistence life style.” “These taro patches over here don’t get much sun when it’s winter time, because the mountain blocks the sun. So just in the last couple weeks the sun hasn’t been going behind the mountain—it’s coming back to the summer—spring and summer. So it’s getting more sunlight for the taro.” “Before, you got to really be prepared,” Uncle Tom says. “Like winter time, we get this Kona wind. The Kona wind used to come here like hurricane, used to blow the roof off people’s houses, broke all the roof. I know all the roof went flying out plenty time in winter months. The wind was strong, like da kine 80 mile wind from down here. And rain: when it rains it rains, crazy kind of rain, like how we get crazy kind of rain several times during the year. It used to rain before—that’s why we had plenty water. That’s why I tell you guys—760 inches of rain on Wai‘ale‘ale but now it’s only half way. Think about it now.” Kaua‘i has been more susceptible to being hit by hurricanes, including Hurricane ‘Iwa (1982) and Hurricane ‘Iniki (1992). “My engineer told me ‘Don’t put big nails in the roofing,’” Samson recalls, “‘because you gotta decide what part of your house you want to lose. You want to save the house, yeah, but there’s not no way that you’re going to save everything. There’s no more guarantee. So you gotta decide what you want to lose.’ So he tell me, ‘Either you want to lose the roof? Or the house? "So when you build something , you make sure you use the nails are small when you put the roofing, enough for hold everything for normal whatever, then if too strong, you let the wind take the roofing.’ Jerry’s house, two hurricane, only lose the roofing. So who am I going to believe? That house, two hurricane, and really take a beating, the houses took a beating, but that house, only the roofing.” “Research can help the community achieve what it wants for its own place,” Kawika says. “In the time when our ancestors had such an intimate knowledge of all of the cycles and the relationships in nature, we had these proverbs come out, like the one I talk about most often is, ‘Pua ka wiliwili, nahu ka mano,’ which means ‘when the wiliwili tree flowers, the shark bites.’ And every year when our wiliwili tree is flowering, all in the news: shark attack here, and sharks attack there, just like that. I know that, and so when I see that tree, I know, okay better be careful and think twice about going surfing when I see the flower. “What it corresponds to is the pupping season of the tiger sharks: the tiger sharks come in and give their pups and probably the moms are just super aggressive trying to protect their babies, or in a bad mood because they’re in labor and they just bite people. They don’t really eat people, they bite people, but a big shark biting is going to mess you up.

“Those are the kinds of things that come about when you have intimate knowledge of things that are happening in the mountains and the ocean. We don’t have that anymore. In Hā‘ena we’re fortunate to be a community where people have very intimate knowledge of certain aspects of this system, so we have fishermen like Uncle Tom, or even Moku here who has extremely intimate knowledge of what’s happening in our ocean. We have our own people who work in our nature preserve on the habitat protection and ecological restoration in the valley. They have a very intimate knowledge of what’s happening the upper forest with the plants and the birds. But we don’t have anybody really in the community who has both realms in their sphere of daily experience. “And so one of my graduate students is trying go back to the old Hawaiian moon calendar. She has this whole big chart of occurrences in the heavens—what’s happening with the plants, what’s happening in the streams, what’s happening in the coast line. She is tracking that through the whole year to see what kind of correlations come out, because things are different now.

"We’ve had all of these species go extinct, so whatever proverbs we had that are associated with those are kind of useless to us now. If something tells us when a certain kind of flower is opening up, and that kind goes extinct, we’ve got to figure out another way to recognize when the event in the ocean is going to occur. “We’ve had a lot of new introductions—we have mango trees and albezia trees and all these new species that are part of our system now. And things are changing with global climate change. So how can we see what’s happening now? What correlations are there now between we what we have here and how can we bring this back with the language and create new proverbs again that talks about what happens here in Hā‘ena? It’s a really exciting project. And t graduate students are relatively young and they can come here and engage with their peers in the community and excite them about this kind of stuff. It’s a very long, slow, generational process to rekindle that relationship, but that’s the way we’re approaching it.” Click here to read about making a local calendar.

|

|

|||

|

The variations in rainfall within Hā‘ena itself makes for different vegetation and forest zones.

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

| Copyright 2018 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||