|

“We ran away from there, because, we would hear this wrack, wrack, wrack, wrack, you know and the thing would go inside of there. Go inside, was coming back, the back wash. And we didn’t even look at this side, how that thing would come in side from the down side. We never even see that because that bush, had the bush all over there, so we couldn’t even see that. And they had houses down there at that time. We couldn’t look because had the cottages, and we were busy unloading the net. That’s what we were thinking. And then when we hear the wrack wrack from the houses, the wave was trying to crush them above us. When we look up then we see the water coming down, just like you guys see the wave in Japan, that’s why we started to run—running straight for the corner.

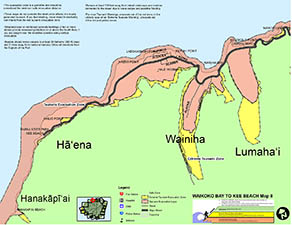

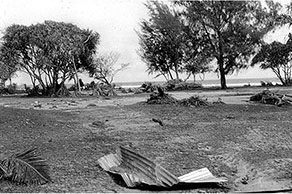

A party at the Rice home at

Hā‘ena, before the tsunami. Pacific Tsunami

Museum Archives: Rice Collection.

“And at the time what was lucky was, I don’t know who the people wen go clean all that place, the guava trees and palm trees whatever, and stack them against the false kamani trees, that kamani line there. But the water came, like the rubbish pile is like fifteen feet. Way inside now. We’re in the tree, the folks was on the rubbish pile holding the tree, the two old men was holding the tree, me and my brother, was four of us was in the tree. Because we were young, you go climb in the trees, naturally you see that.

“So the first house came right by the gate where the line of trees start, all broke. All smashed. And then the other one sail right through, it come right on the side of us. This is way, way high you know, in front of our houses, but far from the beach line to where the house came, was far. I would say—they moved the house maybe, from the coconut trees down there by the road. The house would come inside and line up right along the other side…it was kind of far. Because the thing was floating, coming through. The whole house. And there was the hall, the church hall. The church hall would float like that and come right there and come right on the side of the trees, the thing just came around on the side and then it hit the hill, so when the water did go back it just sit right there like that.

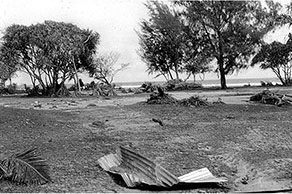

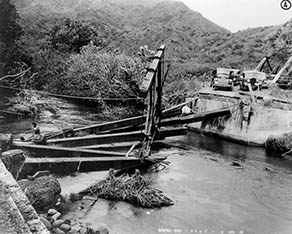

The same location, after the tsunami. Pacific Tsunami

Museum Archives: Rice Collection.

“At the time, we didn’t know. We just stood there, we don’t know what the hell was happening. So all what we thought was our Mom, because our Mom was home with this other lady. Da kine Hanohano wife and the baby. The little girl was six years old then. My Mom was carrying my brother, my kid brother. She was I think eight months pregnant. So we run home. I call, call, call for my Mom, and faintly we could hear that she was in the back of the hill. So I run over there, go see my Mom. My mom was completely nude. The other lady had her pajamas rip off from here down. And the lady, she had the little girl.

“In the back of our house there used to be plenty of palm trees and lantana, and a barbed-wire fence that belonged to Robinson. Right in the back of us, maybe twenty-five feet. And then it’s plenty of lantana in the back of our house, all tangled, lantana growing maybe about six or seven feet. And then a mass of plum trees. At that time, they never clean that place, they had the trees over there. That was the barrier between us and the hill. And in the back where my mom was, had the kind of kamani tree, in the back where they were. That’s where they was when I was running out, grab one sheet because our house was against the trees, was up like that. So run in the house, grab one sheet for cover up my mom.

A sign at Hanakāpī‘ai Beach warns visitors to move to high ground above a safety marker if the water recedes—the warning sign of a tsunami.

“From there we walked across diagonal to another fence line, way up and then we could hear the water coming, from the trees—Wrack! Wrack! Wrack! So it was kind of far for us swim too. Oh, my, I would say we had to swim maybe about forty feet. Because in the back of that place get one deep ravine, like one river, one drain, it filled up too from the first wave. So we had to swim through that, holding the fence line. The old man would take the two women across with the baby.

“We just got on top the flat, the trail in the back of that place, the waves came, sweeping down. By that time all flooded already, when these waves came down. We climbed up the hill, we looked at the YMCA. There were eight or ten cottages over there. It was all flat, gone. And the theatre where we used to see all the movies for the school—flat. There was a wall around it, no more the top. And then we look at the place that was all hala trees—flat. The trees were all back at the base of the hill and all in the rubbish over there.

Search for bodies at site of Mormon church in Hā‘ena. Photo by Orville T. Magoon.

“We couldn’t go home for six months because of the dead fish. Tons of fish, tons of fish all in the low spots. You go there, all rotten fish, so we couldn't go home, the place was so smelly. That’s when we go up Wainiha, we lived with our Grandpa for six months up in Wainiha Valley, about the Firehouse road. We lived with them for six months and then we went home.

"And at the same time the Civil Defense was trying to help relocate the people, building houses. But we never get one free house. We built our own house. But they gave you time to do that and they gave you the mechanized equipment and stuff for drag them back and all that. All the people had to go resettle again. The one lose their house, they had new house from the Red Cross. Everybody had one three-bedroom house.”

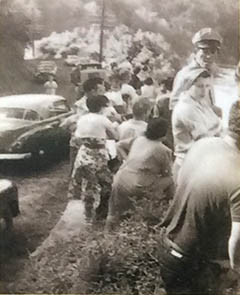

The second tsunami hit in 1957. Seventy-five homes were demolished or damaged along the fifteen-mile strip between Kalihiwai and Hā‘ena—including 25 of 29 at Hā‘ena itself—leaving around 250 persons homeless. Six Kaua‘i bridges were washed out, including the bridge at Kalihiwai, isolating 1,000 persons on the Hā‘ena end of the road. Fortunately, no deaths or injuries resulted from this event.

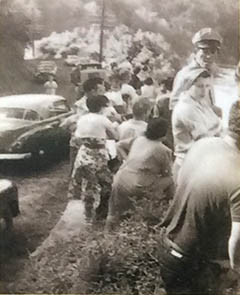

People watched the 1957 tsunami from a hill in Kalihiwai. Pacific Tsunami Museum: Rev. Samuel N. McCain Collection.

“In ’57, that’s when we see how that thing happened,” Uncle Tom remarks.” By ’57 I had a family. So we went over by the Wichmans, and where you come around that bend, the water was already on the road. We knew right from there it was on the top of that place, above the road looking all this thing happen. They say it was 8:45 and dark. The water was rising, coming inside, just kept flowing. Building, building, building, then would come right out where we were, on the low side. And then from there it receded, went out. That’s when we see how far, because we were right there looking at that.

“When it came back, it came bank over the bank. We were out there on the top side, so we could go higher in the back. Because over there it goes up. But our cars were all the way back at that wet place, by the spring, that’s where we had parked. Because we know the water wouldn’t come over there because on the far part, it’s all swamp there, low. So the water would just go right through there, and that’s what happened. But the water wen go inside, come out, go straight like that and wrap around and come along the wall. Knocked all the wall down, buckled the garage doors at the Wichmans, and then emptied down in that low spot right around the bend. But we climb all the side.”

“We had to evacuate,” Kelii recalls. “We had the knowledge of what we had to do, man. My father said, “Let the horses go, let the dogs go, let everything go.” If we have to go, the safe ground was by Hale Pohaku. On top the hill, by the Wichman’s.”

“My Dad was always one lookout man,” Samson states, “a light sleeper. He just tuned into that kind where you don’t know if anything bad can happen. He had that kind of sensitivity. So that day he made sure that nobody go nowhere, stay home. And he’s out there. And I know it was right in the pipe going up, and then I saw him, he put his head up and he was trying to attract and then after that he said, “RUN!!!” And when he said ‘run,’ I was still making my circle, on the bike in the field, for turn around. I was making the turn, I saw the wave hit that wall and splash out, you know. Not one small one, that thing. You know there’s one bank at the edge of this, kind of a high bank wall. Well, when the thing did, I could see the splash.

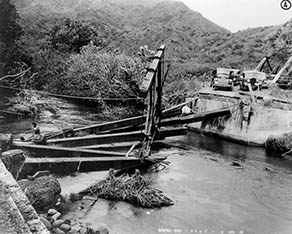

Wainiha was badly hit.Pacific Tsunami

Museum Archives: Arthur Rice Collection.

“I turned and came up right here on the other edge, just going to hit the fence right there. Dad said, ‘Run like that hell!’ He lifted the wire up for me because it ended up right about this area right there, there’s a mango tree and some other trees, that’s as far as they could go. When I ended up, went the other way from fear when I was running on the flat, and then little incline near the base of the mountain, and little bit more incline. And then over here on the right side, right to this big ridge in the back of us. And beyond that is the valley, when you go through the park you can see the valley inside there. We used to go play up there. But I figured I gotta go up there and then I can see what’s going on. But then I was laughing. I figured I was safe but I was in a running mood, so I wanted to get up on a higher ground and I wanted to go up there, because then you get the view. When I went there I saw two waves come in—not the waves but you know that thing came up so high then, it just coming through.

“But I don’t know what wave was that, because, how much slope. We ran because I saw the waves splashing against the wall. All that time, I don’t know how many waves came. But I saw two because the first one I saw, oh, the chicken coupes were rolling. Whatever houses are there it took them that way instead of here. So afterwards I just braced them up and pulled everything up.

The electrical poles were knocked down. An LST landing craft was used to bring in new poles, bulldozers and supplies for residents. Pacific Tsunami Museum: Hobey Goodale Collection.

“Our house was high—big house—that thing went about, moved this much, on the legs and then that thing just went like that. Kind of leaned back. It never leaned too bad. The house was high and that thing had enough, after the first waves came, they were small enough. So when any wave come it just goes through, don’t pick up nothing. But the house in front of us, yeah, that’s what the water took, because there’s the cave area and then over here is one low area because of the reef on the outside takes the central force, hits that wall over there. So you get maybe about three different forces coming in here.

“The water would come straight inside and then if you filling up, it comes over that ridge, this side ridge going to be narrow. So if it doesn’t come even then that going need help with this thing coming. They going to follow this way, inside this lower part. Because this other house here wen shove them up. So I think because of that land protruding out, would take a force from this one. That long barrier, everything that was there came up, may be halfway, and up on the flat was weaker then every other place. Because it came from here, whatever caught this side, the rest would bounce off and go to the wider area. Because going through the bushes that thing wall up, slow down—so that thing went any place where free for flow.

“Afterwards we came down here, pick up iron roofing, and we went up there where the water tank is at the base of this river right there. Water. One lean-to. Our horse that was tied out here, right on the highway when you go down here—that open field right there—it was tied right there and he was up there eating grass, but he had a strong neck.”

|

|