|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| |

|

|

Approaching Mogmog amidst the hengaw, or white-capped terns.

|

To learn about "coming ashore" to this or any other Outer Island, we must go to a teacher of navigation: Steven Tilwemal. “But before we begin talking about navigation,” Mariano instructs, “we say we ‘open the mat.’ The mat is a teaching venue for navigation. There are special people belonging to special institutions that can open a mat. But as we listen to Steve, even though we will be talking about navigation, we must keep it on a rather general level. We ask Steve , ‘according to your experiences in the past….’ Then Steve can talk more freely that way and not, ‘this is how people do it.’ We say it in that manner, because their experiences may vary.”

|

||

|

|

||

Steve opens the mat: “The stones placed on the mat are representing the stars. There are many ways to learn about the stars. First what is called pafis, we have to learn the names of the stars. Then afterwards when you have learned the names of the stars, that’s when you get to learn the positions of the stars. "When you get to learning the position of the stars in terms of directions around the compass, there are names of each star as it rises and as it sets. That’s how you know where to go. To learn about stars is to know these names, and then you get to know the position of each star. And then the next is what star is for what island."

|

The mat is opened....

|

|

"This will differ depending on what island you’re on. Because from the island you’re on, to go from here to there is a certain star. And from here to another island is a certain star. When you know all this from the island you’re on, then you take up, ‘what if you are on this other island?’ So it takes a lot to learn. "There are navigational chants to help you remember all of these. And also to help whenever one is confused out there; by singing the chants, then they trigger the ‘oh, then I’m here.’ We also have a voyage chant, for when we are about to sail. People will come and sing the chant, the departure chant."

|

|

|

|

|

"When planning to travel, the navigators go out to the Eastern part of the island and observe the Eastern sky, usually at dawn, at sunrise. As the stars start to rise in the East, they watch the stars. If there is a particular stormy star that has risen, then you know it may not be a good time of the year to travel. Or if clouds rise quickly in the East, they will keep observing until they cannot find any more clouds. "If from two to four days the East remains clear, then you may travel. Then you have to prepare the provisions for the voyage, food and drink. When you have collected enough provisions for your trip, then you are ready to set sail."

|

||

|

|

||

"All of these islands have their own islands as reference. There is a land reference that shows us whether we are going in the right direction. We call this iteet. That’s the island where you’re traveling away from. As you travel away from this island, if the island stays in the same direction, then you know you are making the right direction. If the island moves or shifts to another direction, then you know you are moving into another direction. “Learning navigation, you know the distance between different islands. As you sail away from an island, until the island disappears on the horizon then you have passed that we call yedaeg, and that is a unit of distance, like saying 'one mile.' For example, the distance between Ifalik and Woleai is only three yedaeg."

|

|

|

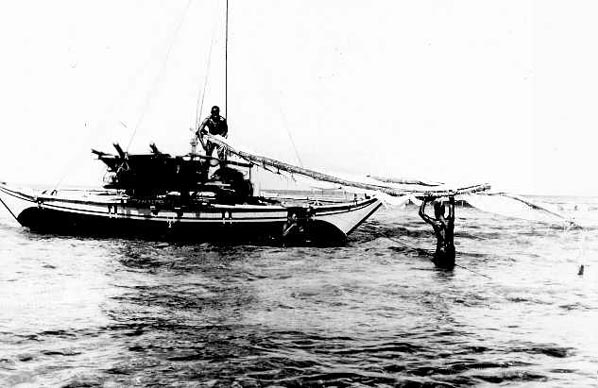

“After the first yedaeg, meaning the island has disappeared, there you will place a big ocean-going canoe—imaginary—there at that point. And so you continue on, and when you think that that big canoe has disappeared, you’ll know you’ll have covered another yedaeg. And then you place another big canoe there, and that’s how you measure the distance. “If we have traveled from Ifalik to Woleai, once we have reached Woleai, canoes from that island will come out to check out our canoe, where are we are coming from, or what’s the purpose of that trip. "And as you travel to each island, when you enter the lagoon, there are particular places that once you reach them, you have to take down the sail. There are certain boundaries where you have to take down the sail before crossing to go ashore or get closer to the island."

|

|

|

|

|

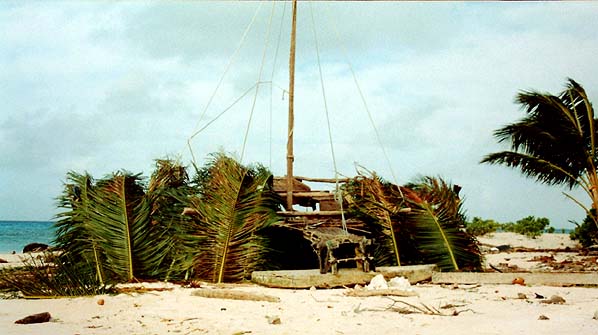

“When we reach the land, we pull up our canoe on the beach. The islanders usually help in pulling it up, sometimes it’s the islanders that pull up the canoe. When the canoe is settled on land, then we’ll go to the Men’s House to report that trip. The islanders will prepare food and bring it to the Men’s House. After the reporting of the trip, the sailors are free to go visit relatives or roam around the island. But the navigator remains in the Men’s House. So the captain remains at the Men’s House while the sailors are free to go around, visit relatives. "Now let’s say we are returning back to Ifalik from Woleai. We have observed the weather. The weather is right. Now we prepare the provisions, do necessary repairs on the canoe. Now we’re ready, we pull out the canoe, we say goodbye to our relatives on Woleai and then we sail out of the Woleai channel and we set sail for Ifalik."

|

||

|

|

||

"We set the landmarks as we sail away from Woleai, and we keep on observing and watching the land reference in the back of us, before it disappears. And we find that to be in the very exact position, so that we know that we are on the right track. We are sailing in the right direction and Woleai is getting smaller on the horizon, we continue on sailing. Everyone is happy. "Then Woleai is getting smaller and smaller, and finally Woleai disappears on the horizon. Then we know that one yedaeg has passed, and then we place an imaginary big sailing canoe there and we continue on. We sail and that imaginary big sailing canoe is getting smaller and smaller on the horizon. When that first imaginary sailing canoe disappears on the horizon, we should have covered two yedaeg already."

|

|

|

“And now the clouds are coming, huge heavy dark clouds and the wind has started picking up, the waves started rolling, and the canoe starts rolling from side to side, and we can hear all this creaking, and then finally the wind picks the canoe and the big waves start pouring down, like pouring water from a basin; the baler is really busy, baling out the canoe, but the waves are coming over the canoe. "We’re sinking; now what? The sailors will put down the sail, roll it up, adjust the mast to be really straight, and secure it in place—tighten up all the ropes. The canoe has swamped, so now we take the sail, we turn the sail and put the one end of the sail out on the out rigger, because that’s what we’ll use, that’s what going to help us in resurfacing the canoe."

|

|

|

|

|

“Now, taking one end of the rolled-up sail, we put it out on the outrigger. The other end is attached to the mast. So, when we go out on the outrigger, we can pull on that sail, the angled sail. And that will turn the canoe. It pushes the outrigger down in the water so the canoe is coming up. So when there is no water, inside the canoe, then you jump out from the outrigger and the outrigger is coming up again. Once the hull of the canoe is emptied of water, you just let go of everything and the canoe surfaces again."

|

||

|

|

||

“Before the storm hits, the navigator tried to memorize where the wind was coming from, and which way the waves are rolling. Because after resurfacing the canoe in the storm, you still have to direct your way out the storm. So the navigator will still know where they’re directing and of course they’ll know what direction we should take to go back on the course to that island. Whether the wind shifted, he can tell. “But one canoe, after a storm that hit them, they spent ten days lost on the sea. Then they used fortune knot-tying, and the knots told them to sail due South. So they sailed South and that’s how they met up with a ship, which rescued them." "Once we return to the home island, there’s usually a celebration, which is called hatariy. So after the hatariy, the celebration, then the sailors are free to go about the island."

|

|

|

"As for the poor navigator, he must stay put. Between Ifalik and Woleai is three yedaeg, so after that journey, the navigator should not be walking around for three months—one month per yedaeg. "He can stay in the Men’s House or at his home, and he can go to the necessary places—the beach and the ocean—and return to his home. Of course, he can go back sailing. He cannot go wandering around on the island, but he can wander around on the ocean. That’s a traditional belief and practice. Because sailors believe that if the navigator starts wandering around on land before that time is up, then once he sails again, he might get confused on the way. "So when he has to start seeing the imaginary canoe, he might be imagining a small canoe instead of a bigger canoe, which will disappear on the horizon very quickly while you’re still halfway between one yedaeg. And that happened to some people in the past."

|

|

|

|

"We have covered aspects of navigation, sort of in general," Mariano states. "And now that this lesson is concluded, we should roll the mat up again, to be put away until such time that the navigator is paid again to open the institution. To be open again, it doesn’t have to meet a certain number of students. A single student, if they can approach the navigator appropriately, a single student may re-open that mat. "If the student still needs to learn some other things, he can visit his uncles, his fathers; or if the next teacher is not a relative, the student can still pay him to teach other aspects that were not learned, by means of making tuba and giving this to his new teacher. Because when they sit down to drink, that is when they share this information. "But now we are rolling up the mat to be put away, until such time that the navigator is paid again to teach, and that is when the mat is re-opened.”

|

||

|

|

||

Sailing and navigation play an important part in understanding the culture of Ulithi and of Yap State, and we will hear more about it. Meanwhile, our attention turns to those who arrived in ancient times.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ulithi Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||

|

Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |