|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| |

|

|

|

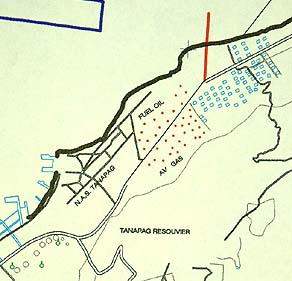

“According to the military map, this is a Formerly Used Defense Site,” Juan says. “From where we are now sitting, due east there were fuel reservoirs. One million gallon reservoirs. Just like they have now down by the harbor." “We have these dumpsites left by the military," Ben adds, "and we have the fuel farm, and we have the PCBs, and heavy metals such as zinc and lead. Those are very toxic chemicals and elements."

|

||

| |

||

“There were forty-four fuel tanks in Tanapag,” Sylvestre begins the story of the fuel farm, “These were for supplying fuel to all those airplanes coming in. There were four airports around the island, plus the seaplane ramp, and these were very busy areas during and immediately after World War II. Very busy. "And these fuel tanks were providing fuel not only for the Navy airplanes, but also for the ships: for destroyers and aircraft carriers. That would give an idea of why all these fuel tanks were placed in different areas."

|

|

|

“We called it a ‘fuel farm’,” Ben recalls. “Huge tanks were left here after the Navy moved out, with leftover oil in them. I remember vividly, when we went out during the rainy season, we would be walking in water full of oil, and catching crabs there. And that benzene product of fuel is very toxic and cancer-causing. Toluene and all of those chemicals are probably all over in these wetland areas.” “When they cleaned that land to give it out as homesteads, there were bulldozers, D-8’s, that just broke those things down,” Juan says. “And oil went all over. People cleaned up the pieces and put out trash and burned it. "And while they were burning wood and grass, man, you’d see black smoke, like Kuwait! But people didn’t know." |

“During those times, the people were not as informed or educated as the residents now. So when the military left these things behind, the people didn't go up and say ‘Yeah, you take your trash now.’ The only thing that they knew how to say is 'Yes, sir!' The government back then was NTTU which is run by the CIA. Whatever they leave, anywhere they have projects, the villagers are not going to touch it, but they’re not going to tell them take it, either. They will just leave it there. “Remnants of the tanks are still there,” Ben adds. “You can still see the metals. They are generally dilapidated. They rusted out and they just kind of folded down.” "They just left those behind," Sylvestre states. "Were they full of fuel? An Army Corps of Engineers study concluded that nearly one million gallons of fuel are missing. No one knows what happened to it."

|

|

|

|

|

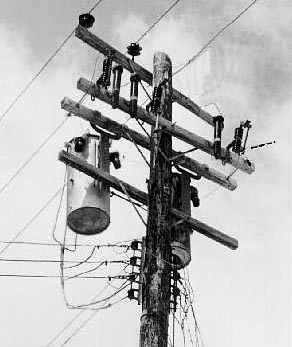

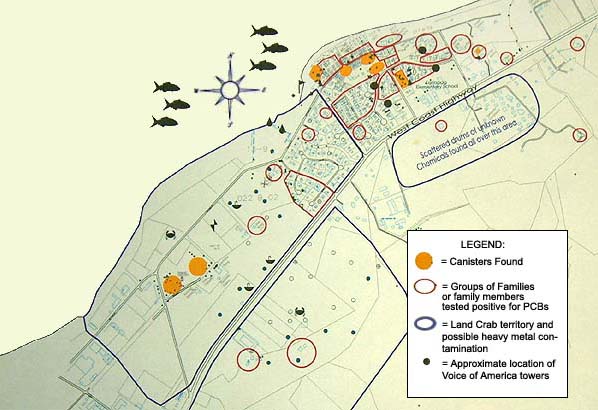

“Then transformer canisters were brought in somewhere around 1968, 1969," Ben explains the origin of the canisters with PCBs, "These were widely spread throughout the village. The canisters were owned by the military or the Navy, and they were to be taken back to the United States, maybe for disposal, but they ended up here as a trans-shipment and never left. "We know that approximately 200 of these canisters were brought in from Kwajelein Atoll in the Marshall Islands, and only 54 of them are found today. And quite a few of them are found in the ocean. Or on the beach. Where we fish."

|

||

|

|

||

“They were stockpiled down near our cemetery, and then they started giving them to people to use for barricades—beach barricades, church barricades, baseball barricades, school barricades—and they ended up in the village.” “Some used them as decoration around their properties,” Juan explains, “because they looked very nice. You didn’t need to paint them because they were already brown. “Some people used them for barbeque stands. They would burn it, oil would leak out, and we would push the oil to the side; some got burned in there with barbecuing."

|

|

|

“The capacitors were right alongside the base of the Voice of America towers. When I was growing up, the towers were not in operation any more. There were four towers, and right in the middle of the four towers was a huge quonset hut, about 100 feet by 50 feet. And inside this quonset hut there were capacitors all over. "When it was not in use any more, the Pangelinan family fenced in the tower and raised goats inside, and we used to herd the goats into this quonset hut, close the door, get up on the beam, and jump down and start riding the biggest goat. “And when I was really sweaty, I loved to hug the capacitor. It was very cold. Just hug it. In mid-afternoon, you could see the dew on them, the condensation. Then when they moved them to use as barricades at the baseball field, right after practice we would all run to a capacitor just to cool off."

|

| |

|

|

“We eat a lot of crabs,"

Ben says. "and one day we learned about this contamination

from the transformers. We didn’t know that it was toxic or carcinogenic

to our health, and we continued to eat crabs. "Then our Public Health Office put out an announcement that because of the contamination of PCBs in this village, they’re advising the public not to consume land crabs."

|

||

|

|

||

"I was a student at the University of Guam," Juan relates, "and I was doing research at the Micronesian Area Research Center, MARC. And I started coming across some declassified military documents about the Navy and the NTTU administration. And I read that for some of their antennae, they were using capacitors, which contained PCBs, Polychlorinated Biphenols. "PCBs had always been used, but then they stopped manufacturing PCBs in 1954. I thought ‘Wow, something must be wrong with this.’ I started reading more about it, but there was very little information about PCBs. I started asking, and I learned ‘Oh, they stopped manufacturing PCBs because it is suspected that it can cause cancer'."

|

|

|

|

"Capacitors? What is this? In Saipan, I saw a lot of them in the village and elsewhere. So I brought it up. But back then everybody thought I was crazy." "Then one of the canisters opened at the Head Start, and kids were playing with the oil. And then one eight year old boy who frequented the social hall died with just like a pimple on his side. He was crying and crying, and then they took him to the hospital and found that it was cancer. He died. "So we started complaining, ‘What is that oil? Come and clean it because it’s oil.’ We took it and tested it on Guam and it was PCB. I brought it up in 1982. They finally realized that it’s PCB in 1988."

|

|

|

|

|

“When the Navy was here, they also had two dump sites up the hill," Ben says. "These two dumpsites were in dry creek beds, and they filled up the dry creeks. The village of Tanapag is bounded by two dry creeks, and during the rainy season, these are active waterways that take down debris right into the ocean.

|

||

|

|

||

"So after every heavy rain we would find dump truck tires and barrels of oil floating down into the ocean, and more are still buried out there in the lagoon. "There is used oil, from when they changed gear oil or crankcase oil. They would put it in barrels and dump them up there in the dump grounds, along with airplane parts and airplane engines. Of course, people in the past collected a lot of this metal and sold it for scrap, but still a lot remains in there." “Tanapag is a lowland area,” Sylvestre adds, “and it’s prone to flooding during rainy seasons. And when that happens, it spreads the contamination very easily and quickly. So we have those kinds of fears and anxieties from the community. Not only are they worried about PCB now, but also these other chemicals."

|

|

|

“When it’s low tide we used to dig for clams,” Noel says, “but after the PCB contamination came out, then I realized that I’m exposed to all of those chemicals in clams. I remember how every time we went in the ocean to swim we’d step on these metal things. I didn’t know they were transformers, those canisters. They were literally all over the place and we didn’t know." “Sometimes when we’d go up there and look at the ocean, there would be oozing stuff coming out of the water and I’d say, ‘What is that stuff?’ Even the baseball field was littered with those things, and we’d climb up and get some fruits, some mango, eat it, and sit on those canisters. And they were everywhere. "We were so innocent. We’re victims of this stuff. Now we realize that a lot of people from Tanapag are dying from cancer. I think I’m going to get myself a check-up."

|

"Since all of this contamination awareness came out," Ben remarks, "I’ve not seen anybody go clamming on the beach area. I guess they learned about the PCB contamination, and the dumpsites that drain out into the ocean." "When the DEQ and EPA or Army Corp started collecting the canisters," Juan says, "they found several canisters open in the water, in the ocean. But they said that the ocean didn’t get contaminated."

|

|

|

|

|

|

"A lot of our people who have passed away really had cancer," Ben states. "And some of the cancers are rare. Cancer may be hereditary for some communities, but because we’re not known to be a cancer-hereditary people, we’re concerned about what’s causing all the cancer. "But even today, our Department of Public Health and the Center for Disease Control in the United States have not determined whether the PCBs in the village have caused the majority of cancers here."

|

"We have spleen cancer, we have pelvic cancer, we have blood cancer, we have liver cancer, and we have mouth cancer. We’ve got all these cancers killing the people here, and we still don’t know what’s causing it. "Of course, there are still other contributing factors like heavy metals: lead, chromium, bromide, arsenic. Arsenic might be naturally occurring, but not in large quantities, and we think there’s a large quantity of arsenic around the village. "We’re hoping that our Department of Public Health will help us to determine whether the cancer deaths are related to PCB or not."

|

|

|

|

|

| "The military refused to acknowledge that this is a Formerly Used Defense Site—FUDS—until we showed them a map that shows the U.S. Navy boundary and the Voice of America site. Then they said, ‘O.K. Now we agree’. And that’s why some of the Army Corps of Engineers funds were made available to do the characterization and treatment, the removal of PCB and the contaminated soil."

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanapag Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||