|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

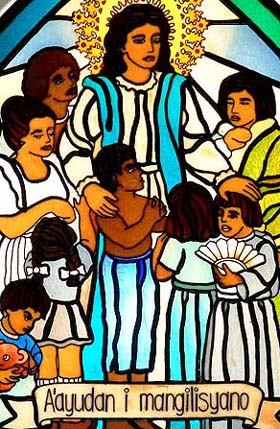

Santa Remedio Church, Tanapag.

|

|

"The church is very important in my understanding," Ben remarks. "In our upbringing, we are all baptized in this church. Every child that is born here is baptized in this church, and so we think it is a very important function to the village. It actually helped us to maintain law and order, continue with the transition of cultures, the melting pot of knowledge and everything else that’s going on. The transition was kind of fast paced."

|

||

|

|

||

“Before the war there were many houses but only two churches on the island, Garapan and Tanapag,” Rosa Castro says. “During the Japanese time I remember the church was constructed of cement. It was concrete style, not blocks, but solid concrete, and at the back of the church was a priest’s convent. The priest’s name was Jose Taidio. The brother’s name was Gregorio. That priest had a car and he would go down to Garapan, because only Garapan and Tanapag had churches." “I was around 13 or so when this church was built,” Pete recalls. “ The old church was right next to where the church is right now. There was a concrete church before the war. Tanapag had the only concrete church."

|

|

|

“All other churches we called ‘chapels.’ But Tanapag was the main church on the entire island of Saipan before. Now Mount Carmel is going to be the head of all churches in Saipan. But before, Tanapag is where they established the main church. But when the war came in, the concrete church was damaged. The Tanapag people built a wooden church right next to the concrete church. And then the church we have now we build right on top of where the concrete church was before.” “I don’t remember the original concrete church," Estella says, “But after, when we moved to Tanapag, the wooden church was already rotten at the bottom. They bulldozed it to the back, and parts of the concrete church were still there. And some of those flowers that they planted before the war were still there. There was a big flower and the blossoms were yellow and if you tasted it, it was sweet. When they cleared it for building the new church, that’s when they took those flowers down."

|

|

|

|

Virgin de los Remedios.

|

“Our Patron is really a fishing patron,” Ben explains. “It’s called Santa Remedio or Virgin de los Remedios. The statue that we have today is a historical statue that originally was on the island of Tinian.” “I heard from the elders,” Rosa Castro recounts, “that when they moved the elders—the Carolinians—from Namon Weite to Tinian because of a typhoon, this leader whose name is Johnson, he brought these people to Tinian. And Johnson’s wife owned this statue that is now here in Tanapag.”

|

||

|

|

||

“Her name was Maria Anna and she was a Spaniard descendant,” Ben adds, “Our ancestors were taken to Tinian to work for Johnson to hunt for goat, to hunt for chickens, and to hunt for cow, and sometimes they would be brought to Saipan to slaughter cows up in the San Roque area called Matansa.” “Johnson had an accident in those times,” Rosa continues, “His ship sank between Tinian and Saipan. So when that incident occurred, the mother of Johnson’s wife came to Tinian to see her daughter. And later on she gave the statue to the people of Tanapag, because she had to leave and she wasn’t going to take the statue back with her again.” “She didn’t want to carry all these things that are fragile,” Ben says, “so that icon came to the village, and since then we've had it here. That happened maybe more than 100 years ago.”

|

|

|

"The church is very important to the community," Rosa explains, "If I have a baby, before I give that baby a name, I have to go to the church and have it baptized in the church. And when children are growing up, the church is important. When they're about five years old, they have to learn how to read catechism for first communion. And after that, when people are going to marry, if they want to marry into the good life, they have to marry in the church. "In our custom before, when you married in the church, that meant‘until you die’— you never separate. But these days, even if they married last week, they find another girl or find another boy around the store or in the restaurant, they forget what they offered at the altar, ‘My wife forever until I die.’ And they divorce and they marry another one. "But before, when you’re married in the church, that’s your wife, that’s your husband forever, until you die. That was one of our regulations in the church."

|

|

|

|

|

“The community is mostly Catholic,” Pete remarks. Pete explains how the Catholic influence also manifests in local names: “I really don't know what my grandfather’s name was when they first migrated to Saipan; I know his family’s name is Seremina. But when I was growing up, his name was Juan Teigita."

|

||

|

|

||

“My grandfather had a brother, and the two of them migrated to Saipan. But when my grandfather was going to be married, he needed to be baptized—in those times, they needed to be baptized in order to get married. So he named himself Juan. That’s a good Catholic name. And for his last name, he picked out a bird name. There’s a bird we call teigita—the red honey eater—so he called himself Teigita. “My grandfather’s brother’s name is Isidro. He was an altar boy before. We call the mass a missa, so he named himself Missa because he was an altar boy. That’s how he got his last name. Isidro Missa.”

|

|

|

“They don’t carry their Carolinian names because the church was very powerful then,” Ben explains. “And because they needed to get married in church, they had to change their name to something that the Catholic Church allows. And one of them, Isidro, is a Saint name, and Juan, again, is a Saint name, and so they used those names. So, here’s two brothers. One is Teigita and the other one is Missa. We didn’t know that they were brothers because of the last names. “My grandfather is Chamorro, so he’s stuck with the Sablan. My grandmother is Carolinian, and even her, I don’t know her name. I only know the family name is Rewal, and she didn’t change her Carolinian name. She held on to the family name from the outer islands of Chuuk. That’s Repekki. But Pete’s grandfather and grand-uncle really had to change their names.”

|

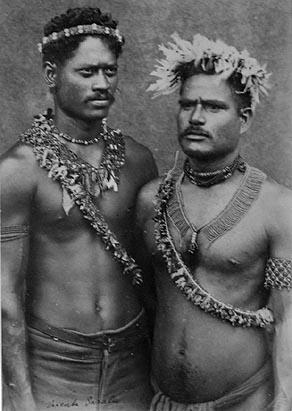

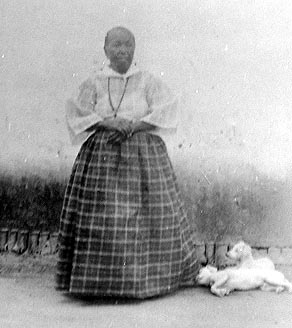

“If you were to say how the Carolinians became Christian,” Noel states, “I will say it was through the Chamorros. They say the Spanish didn’t really want the Carolinians to be Christianized. Even in the German time, the Chamorros were all dressed up nicely, while the Carolinians couldn’t go inside the church because of their traditional attire. Especially the women. So a lot of the Carolinians at that time were not Christianized. "The interest grew by following the Chamorro. They watched the Chamorro, and they just started to get interested. And then every time the Carolinians wanted to go to the church, they started to wear western clothes. “When some of the Carolinians started to wear clothes, all the rest of the Carolinians thought it was kind of funny. But that’s how a lot of Carolinians became Christian—through the Chamorro. And this is coming from my grandfather too. He told me about it.”

|

|

|

|

|

| The church may be a Chamorro influence originally, but its traditions span across both Chamorro and Carolinian culture histories. Chamorro is the language that predominates here, but Carolinian singing is a prominent feature of the Tanapag congregation. Similarly, the cemetery is a place that intermingles Catholic-Chamorro and Carolinian traditions.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanapag Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||