|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|

|

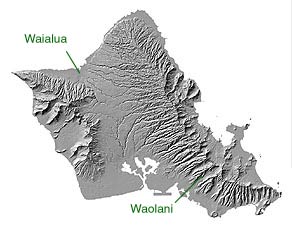

Waolani, the abode of the gods. Here Kahanaiakeakua

was raised.

|

| Nu‘uanu is mentioned in many early legends, but the most important of these to the valley itself is the story of Keaomelemele. This once-famous story was told by Moses Manu in 1884. His version was printed in the newspaper Ka Nupepa Ku‘oko‘a, and ran 31 consecutive weeks. A translation of this manuscript done by Mary Kawena Pukui, and a newly edited version reworked by Puakea Nogelmeier has been published by the Bishop Museum Press. Puakea tells us that this story explains the origins of Nu‘uanu, as well as the origins of the mo‘o as a class of spiritual beings in the islands. Listen:

|

||

|

|

||

|

Keaomelemele is "the golden cloud."

|

"In this story, there are five children of the gods. The eldest is Kahanaiakeakua (Ka-hanai-a-ke-akua), who is raised at Waolani. Kahanaiakeakua is the child of Hina-welalani and Ku. And then Paliuli, who is raised at Paliuli, on Hawai’i Island. Keaomelemele is the heroine of the piece, but she’s actually the third born child of the story. "These are all born in Kuai-he-lani, the mythical, mystical islands far distant. But they are placed under the guardianship of Mo'o-Inanea, a sister of Kane and Kanaloa, who dwell at Waolani. "Kane and Kanaloa find out about the birth of Kahanaiakeakua. They send their other sister, Keanuenue, to get the child, and he’s to be raised at Waolani."

|

|

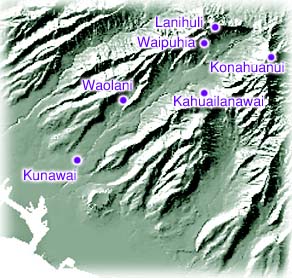

"Now the setting at Waolani at this time is that there is no valley of Nu'uanu. Waolani connects directly to Konahuanui, the mountain behind, and it’s inhabited by all of the spectral creatures: the ‘e’epa, the hunchbacks, the red-eyes, all the bizarre characters. "That’s who Kane and Kanaloa want to be the caretakers, under Ke-anuenue. They don’t want anyone around the child that would distract either the child or Ke-anuenue. So they pick all the po‘e pupuka (ugly types), all the ‘e‘epa, and that’s who is set to work refurbishing Waolani. All the paving is renewed, all of the stonework is redone. They beautify Waolani and get ready for the raising of the child. And there Keanuenue raises this child to adulthood, as her foster child. "Then Paliuli is born. Two guardians were sent to fetch Paliuli, and they were women who lived at the peak of Lanihuli. One was named Lanihuli, one was named Waipuhia. After they bring Paliuli in, and she’s put into the care of Waka, they are allowed to go back and live on top of the Ko‘olaus. Paliuli is then raised under the care of Waka, in Ola’a, at Paliuli." . |

||

|

|

||

| "When these two children come of age, they are married together. But Ka-hanai-a-ke-akua is not very faithful, and Paliuli ends up despairing, and running off. She enters a halau on Kaua’i and learns the hula. "But in the mean time, Keaomelemele, partly to handle the family dilemmas, has come to live at Waolani. The siblings aren't there anymore, however, because Paliuli and Kahanaiakeakua are on other islands. So Keaomelemele comes and she is offered to learn the hula. Kane and Kanaloa bring Kapo—not Laka, but Kapo—to teach her personally. "So Keaomelemele is trained in the hula. Her training under Kapo only lasted two anahulu (the anahulu is a ten-day span, a period that’s used throughout this story). Then she has an uniki—the formal graduation at the end of training in the hula. Not long after her uniki, Paliuli comes, and she and her companions learn the dance--now from Keaomelemele: she in effect is the kumu now." |

|

|

|

"Once they’ve learned the dances, they all begin to dance together, as a group. And they dance. And after five days of non-stop dancing, the Island of O’ahu starts to shake and reverberate, and by seven days, there’s lightning, there’s thunder, all the godly signs are coming into place. And as the anahulu closes, all of the mountain, the side of Konahuanui, crashes open, and a huge cleft is created. Waolani is separated from Konahuanui, and the valley of Nu’uanu is formed."

|

||

|

|

||

|

"...after five days of non-stop dancing, the Island of O‘ahu starts to shake..."

|

| "A whole family change is now taking place, with who’s in charge of what powers. In the process, Mo‘o-inanea herself comes to O‘ahu from Kuai-he-lani and Ke-alohi-lani, the lands in the clouds. With her, she brings the mo‘o. And she brings a procession of mo‘o that starts out in Waialua, and they march into Waolani. By the time the first ones reach Nu’uanu valley, the end of the procession is still at Waialua. "It was implied in the story that all of the mo'o were in effect her descendents, her offspring or some aspect of her. The story identifies some of those mo‘o individually, and mentions where they lived. Different mo'o took up residence in different places, like Kunawai, and Moanalua. Many of them remain nameless, and they just take up the watery spaces. Other stories get more specific in their geography, but that becomes another piece of the legend."

|

||

|

|

||

|

What are the mo‘o, exactly? “There are mo‘o that are simply lizards -- the mo‘o of the house, that’s a little wall lizard. And the term is used for lizards, but it doesn’t tell you that these were necessarily lizard formed. It’s hard to say that mo‘o are crocodilians or some kind of serpentine creatures. They are entities that are associated with the wet places; they have to reside in the wet. Whether they take the form of a lizard -- because there are mo‘o that are simply lizards, like the mo‘o of the house: that's a little wall lizard. And the term in general is used for lizards. But this doesn't tell you that these mo‘o were necessarily lizard formed. "There just isn’t a reliable sense of what they look like. We have two accounts, two stories of people who saw mo‘o, and dealt with them, and it looked like people to them. Both of the accounts use the same description, in which the whole structure of the face is fluid and keeps moving, so that there’s no way to grasp features. But not that they were shaped or formed like a lizard. "And we know that they appeared as beautiful women, or not as beautiful, but that they had all different forms. Maybe there isn’t a single form of the mo‘o, because in some of the legends the mo‘o’s tongue is an obvious characteristic or feature, so definitely they had a tongue. But to make that a lizard’s tongue is to impose one vision on that. "It’s supposed to be nebulous. Let’s leave it that way. They are mo‘o.”

|

| "In the end, Kahanaiakeakua is brought back into the fold and put into position as a priest (at Kaheiki). Paliuli gets married off to Hi‘ilawe and settles in. As the over-arching, most powerful of the five children, Keaomelemele in the end bestows many of her powers on Kaulanaikapoki‘i, the youngest of the five. Keaomelemele ends up retiring, and I believe goes back to Kuai-he-lani to reside."

|

||

|

|

||

| "Within the story, a lot of tradition origins are mentioned. Ke-anuenue is the sister who’s going to raise Kahanaiakeakua. But she has borne no children. So when this baby is brought to her and needs to be breast-fed, she has no milk to offer. So she goes to the brothers, Kane and Kanaloa, and says 'I need milk for the baby.' And they tell her, take these herbs, and some of them you rub on the breast, some of them you eat, and put this together, and you tweak the nipple of the breast, and boom—it starts to produce waiu, mother’s milk. This is one of the la‘au lapa‘au (Hawaiian medicine) traditions. "Then he (Moses Manu) goes into an explanation that this is how that tradition, that art, began and was handed down from that time. And in his telling of the legend, he says 'compare this, to the foreign nations, who of course take milk from other animals, rather than produce their own.' So they take the milk of the cow, or the milk of the goat, to feed the children, whereas the Hawaiians were very innovative."

|

|

|

|

| "The legend is a source of both cultural pride, and cultural history. The material on the hula, the material on the mo‘o, the material on some of the kilo hoku --the ones in the story who are trained to read signs in the heavens—the training that Kahanaiakeakua gets along with the priestly arts of healing. These are another whole level of the story. Beyond geography, there’s an enormous amount of cultural material in there." There is much more to this story. But now that we are familiar with locations within Nu‘uanu, let us learn about this valley's neighbors.

|

Konahuanui

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

| Nu‘uanu Home | Map Library | Site Map | Hawaiian Islands Home | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||