|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| |

|

|

|

|

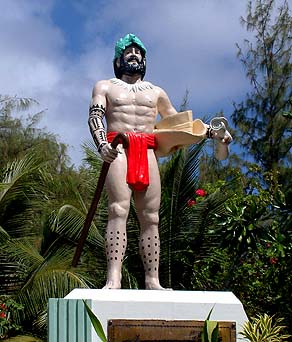

Managaha island sits off Tanapag on the edge of the lagoon that forms Tanapag Harbor. A flat coral islet, Managaha plays two important roles to the people of Saipan. The first has to do with a historical navigator who brought Carolinians to this island. He is important to all the Carolinians on Saipan. For them, Managaha—known as Ghalaghal in Carolinian—was a very, very sacred and taboo place.

|

||

|

|

||

“There is an important navigator buried on Managaha," Ben says, "and his name is Aghurubw. During the German time, even before that—even back into ancient times, the Carolinians were already sailing throughout the central Pacific areas, and they would come to barter, to trade for cigarettes or for clothing, or other goods. But this navigator came with several canoes to settle on Saipan. "Originally they thought Aghurubw was from Satawal, because that’s where he left to come to Saipan. But other scholars hinted that he is probably from the Chuuk side, Puluwat, other islands in those areas."

|

|

|

"Aghurubw brought a large number of Carolinians to settle in Saipan. At that time, the Spaniards had taken all of the Chamorros from Saipan down to Guam, and when he arrived here there wasn’t anybody here. There were houses but no people were found on the islands, so he called it Seipel, ‘empty journey.’ "And when he died, because of his stature in the community, he was buried on Managaha. My recollection of the way they buried him is that they dug not the conventional type of grave where you have a rectangular shape. They dug a hole and they buried him standing up, and the rationale behind that is so that people don’t walk on his grave. If you have only the head and the shoulders, it’s a very small area, and very unlikely that you will step on him because of the area that is covered."

|

"The small tombstone is really depicting only that he is buried on the island, but his body is not in that area. It is really a secret. Nobody knows where he was buried. We only know that he was buried somewhere there. But because of that secret, and the traditional custom of not stepping on his grave, that dictates that he is buried secretly and only a few people know where. And those people who buried him must be dead by this time. "The Refalemei clan seems to be very active with Aghurubw, and so I would deduce that the Refalemei clan is the same clan with Aghurubw. His clan and my clan are different clans. We do not recognize him as a chief from this village because he’s not a chief from this village. He’s from other areas. So normally, people from Tanapag don’t go down and celebrate Aghurubw. The Refalemei clan would get together and invite people and even Governors and Congress people would go down and celebrate, but we normally don’t."

|

|

|

|

|

|

For the Tanapag people, Managaha was the best place for carrying out the Carolinian custom of fiighiiló. “What belonged to a person who died, you take it and have to put it in the casket before you close it,” Rosa Castro explains. “But leftover possessions, the second day after you bury the person you can take all of what belonged to that person and put it in bags. And we get together all the family members and we ride the boat, we carry those to Managaha, where they burn it.”

|

||

|

|

||

“Fiighiiló is the burning of the leftover possessions, the actual burning,” Ben explains. Fiighii means "burn" and ló means "away." Ben says, "We’d burn clothing, materials, and properties of the deceased." “When a person died,” Pete reiterates, “all his belongings were put into the casket, but whatever new things that they cannot put inside the casket, they took and burned that. It’s a special ceremony, held in an isolated place, a secret place. You have to go away from the mainland, and get away from the people.” “And Tanapag is the mainland,” Ben adds, “because there’s a lot of people here, you go down there and you burn it away from other family members. Only your family will go there and help out with disposing of the deceased’s property."

|

|

|

“I attended once," Ben recounts. "I could not recall the person who died at that time, but my adopted father owns a boat and everybody in the village would ask, ‘can we use your boat to take down this property of the deceased.’ And now I know that the coffin is not big enough and sometimes the deceased would have a lot of clothing or materials and it cannot fit into the coffin. The fiighiiló is the one that is the left over that we would go down and take it to Managaha and burn this property.” "Some like me, we don’t go to Managaha," Rosa says, "because we don’t have a boat, we just take it down to Lower Base, next to Dillingham, and we burn there. My niece’s clothes, we burned. We threw in everything we took and we burned it. Some, they just burn outside the house when it’s four days after the burial. That is the custom. It’s a Carolinian custom. It’s not Chamorro, only Carolinian."

|

|

|

|

|

“This was done during daytime,” Pete says. “There was designated a date and time. But usually they would go early in the morning. They would burn everything." While fiighiiló refers to the burning of the belongings, this act is part of a larger blessing ritual, fighrourou. The ritual portion is conducted by women only.

|

||

|

|

||

“In my younger days I was already practical in operating outboard motors," Ben recalls, "because we had one or two of them. We had a couple of boats. My father would own boats and they would ask if I would drag them down to Managaha to do this ritual, and my father could not say no. That is a custom, and my mother Isabelle is Carolinian, so my father would not say no to a Carolinian custom. "So we would go down there and they would just bring up the possession and they pile them up, they get wood and of course they bring food for us and water, and a lot of times, they’ll ask us to go get coconuts for drinking. And they would burn it as they sat down there, and they talked stories."

|

|

|

“The burning is really not an elaborate thing. They just bring from the boat the property or the clothing of this person. They’ll make a fireplace and we’ll go and collect firewood and the older guys would make the design for the fire to be burned, usually not very big. And then they’ll burn. They make sure that everything is burned. Not a piece of cloth is left behind. We would continue to bring wood and continue to burn until it’s all ashes. Sometimes it took two hours. "It was not a solemn event really, just telling stories, just talking about the departed one, what he did good, maybe he’s a good fisherman; what he did right, what he did wrong and the whole deal. It is just a reminiscing. Some ask, ‘Does anybody know his knowledge?’ and others will say, ‘Yes, his son understands this and his daughter did that,’ and that means he handed down his knowledge."

|

|

|

|

"I don’t know if it’s a ritual but some older ladies would take some of the ashes and spread them out in the ocean. That was unique in my day. Both men and women came out to do this, mostly immediate family. It was not elaborate, as I remember, but it was just a ritual that I appreciate very much. "And that’s what we have lost today. I haven’t heard that in a long time."

|

||

|

|

||

We will hear more about traditions passed down from the elders. But first, we turn our attention to the sea.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanapag Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||