|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

“During the Japanese administration, the local people were very happy,” Noel states. “They had more productivity, and the economy was a lot better. There were sugar cane, tapioca, coffee, fishing, and mining industries. But the only set-back for the locals was that they didn’t really have much freedom. Education was up to sixth grade and that’s it.” “Japanese language was taught in the schools,” Scott adds, “and much like in the American period, there was a heavy emphasis to instill their cultural values into the local people. There was state Shintoism and such, especially in the 1930s as the build-up to the war went on. There were a number of Shinto shrines on the island, and you can still see the ruins.”

|

||

|

|

||

“I remember going to Japanese school,” Jesus recounts. “During this school time, we didn’t have a formal education in the language of Japanese, except a lot of practical study in agriculture. The language was strictly Japanese. We were not allowed to use Chamorro language. “They weren’t very strict on the lessons in Japanese simply because they were not interested in how well we would do in school. They’re more interested in how well we learned the trades and the practical knowledge of agriculture. "There were first, second, third graders in those days. That’s the hierarchy. You go to first grade and you learn more about agriculture. You go to second grade, probably you learn more about social life. In third grade you learn more to be an imperialist!”

|

|

|

“In Japanese time, although the locals were limited in terms of education,” Noel adds, “there were a few exceptions. Some of the locals who were recognized as being so bright were taken to Japan to get further education.” “The Japanese Navy really administered these territories,” Scott explains. “They were behind the scenes but they were heavily involved, and heavily involved in the financing. Apparently the money was coming out of China. But the Japanese had turned this place into a really prosperous little cog in the Japanese overseas empire.”

|

|

|

|

|

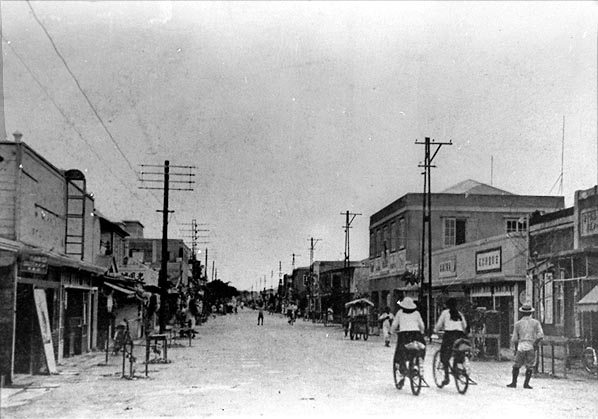

“Garapan was probably not a whole lot different then,” Jesus recalls. “The Chamorros mingled well. The Japanese didn’t necessary mingle with the Chamorros with the exception of their children. Their children could mingle with the natives, the Chamorros. Garapan during that time was nice for us. It was the first time we saw a city. But comparing it with today, today is much more beautiful.” “Local people were making a lot of money, as they do now, by leasing their lands,” Scott continues. “The Japanese leased farm lands and they also leased houses. If you had a nice house lot in Garapan, you might consider leasing it out and moving to your farm and living off the proceeds. So a lot of people made pretty good money just on leasing arrangements. Consequently the standard of living was much higher than it was on Guam at the time. “I think in the 1930s when land was starting to get scarce, the Japanese started to enter into some questionable practices. Rarely was there just outright kicking people out, but they had ways of forcing you. If they wanted your land and you weren’t being cooperative, they had ways of letting you know that you should move, and you normally did."

|

||

|

|

||

“The people now remember the Japanese times as being prosperous. Nonetheless, at the end of World War II there was a lot of resentment, because there had been a real social structure. It was the Japanese, then the Okinawans, the Koreans, and the Chamorros and Carolinians. The locals had a collective name. They were tomin, islanders.' It was kind of a derogatory term that the Japanese used. "The islanders resented that. They resented that they were minorities in their own land. They resented that they could only rise so high within the South Seas government organization. They were pretty much there as laborers for the Japanese, and you had a few of the people from prominent families that were trained to act as intermediaries between the Japanese and masses.”

|

|

|

“My mom was working to clean sugar cane leaves from the dry stalks,” Rosa Castro remembers, “because all around Saipan, there was tapioca and sugar cane. We had a factory for tapioca down there on Lower Base. And the factory for the sugar was down at Mt. Carmel Church. So all the island of Saipan was tapioca and sugar cane. They were the main products produced by the Japanese. “When the Japanese knew the Americans were going to be here, they took all the men. They were put in a camp by the Japanese, as the invasion was approaching, as labor to build what they needed built. Only women and small children were left in the village. That’s when my mom went out helping Japanese to clean the tapioca leaves or sugar cane leaves, for only 3 yen, sannen. And we’d go to Garapan. We’d buy one pound of rice, we buy other fish, maybe like salmon, a kind of pickled or salted fish."

|

|

|

|

|

“When the war was imminent and approaching, our men ran back to the village. The men were taken by the Japanese soldiers to work for the Japanese defense system, I suppose, but when war was imminent, airplanes started strafing, bombing and the men of the village here in Tanapag ran back to the village. But before they came back, we had only two guys taking care in our village.” “After the war, local people didn’t want the Japanese to come back,” Scott says. “That was one of the reasons that, during the early Trust Territory period, the Japanese were not allowed to come in here. No businessmen, no nothing. But now, 50 years later, people are looking back on those times as orderly. Everybody that wanted to work could work. You pulled your own weight, there was no crime. The Japanese had everything organized. There was respect. There were no major problems with alcoholism, crime, juvenile delinquency, that sort of thing.”

|

||

|

|

||

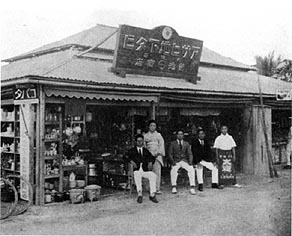

| “A lot of people of our parents' generation, they loved the Japanese era,” Noel adds. “The Japanese leased our people’s land, and the locals had money to spend—maybe they wouldn’t get rich but that’s okay. But the Japanese, you know, they did a lot of good things. They really built Saipan into a modern place and they had a post office, retail shops, and of course the ships coming in and out. "People had jobs and education—just a little bit of education, and I see that today, in American terms, as abuse. But in the Japanese times it was very, very straightforward. There was hardly any crime. You commit a crime, you get severe punishment.”

|

|

|

“I don’t think it was viewed as favorably as the German period,” Scott surmises. “How could you have it more favorable than the German period? Then, you pretty much had the best of both worlds. There was just enough organization and money coming in, yet with a lot of personal freedom. "The Germans let you know what you were supposed to do. You had to pay your tax and you had to do this and you had to report if you owned a cow or something, but for the most part, you were left to do your own thing. It was at a time when people could live a subsistence lifestyle and live very comfortably. The land was so rich at that time."

|

|

|

|

"In Japanese times, you have the resources being destroyed and you had more people coming in, and suddenly the local people are a tiny minority in their own island.”

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanapag Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||