|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Forests are very much, in a way, sacred,” Tina says, “because that is where you get your supplies for your houses, and your canoes, and your diángel—canoe houses. After you build the structure, then you store your canoes inside, like your garage. And diángel would also serve a very important social function. “Palauans also practice a sort of agroforestry. A taro patch, you would go there and not only would you get your taro, but there would be different fruit trees and things, and the streams had a lot of shrimp. Again, the zoning of the environment was very important."

|

||

|

|

||

“There is a term called omelisebekl. There is a difference between hiking—the Western type of hiking—and our concept of hiking. You don't just hike. When you walk in the forest, a father and a son, or a mother and a daughter, you begin to identify where things are in the forest. You identify a tree, 'oh, that is a good tree for the beams of the house,’ ‘that's a good tree for a post,' and 'what is the name of that tree?' "It is very much an educational process. So when you hike—omelisebekl—you are walking the woods and you are looking: 'oh, that's a good clearing, that is meadow, that is a good clearing for some great dry-land gardening' or something."

|

|

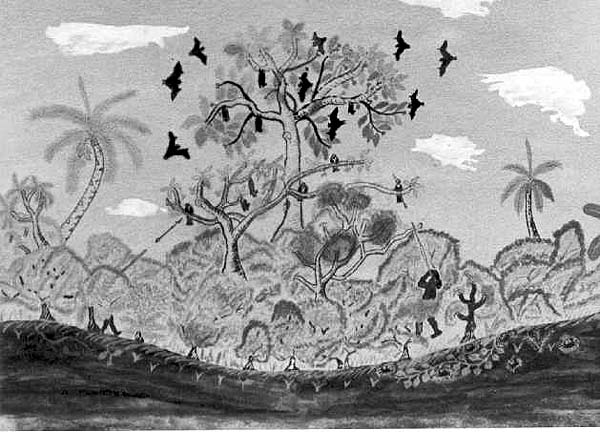

Rock Island forest.

|

“A kid learns the environment by omelisebekl, by hiking. They learn to say where are the nut trees and whether the meat of a nut tree is big or small, because they would get one and open it, and, 'oh this is a good tree because the meat is bigger.' "So you identify in the forest. It is a part of your life, it is part of your home, because you identify where things are. So in all the villages, people would know where things are, and when it is time to, say, build a bai, they would say 'oh, there is a certain tree over there.…' " “When you’re harvesting trees,” Tarita says, “I think it was a common rule throughout Palau, that if you harvest one, you plant five. So for every tree that you cut, you’re supposed to plant five.”

|

|

|

|

“Of course there's ritual for felling a tree," Tina says, "and because there's a ritual, that's why it's sacred. You don't just go there and cut the tree, you have to talk to the tree, you have to communicate with the tree before you actually cut it down. And where you cut it down is also how the tree would fall. So all these rituals go with that.”

|

||

|

|

||

“We believe that everything has a spirit," Kathy states. "Everything—the streams have a spirit, the moon, the trees, the ocean, everything has a spirit. So it's our practice that when you cut a tree, you ask permission from the tree to cut. "And to make a canoe, not any old big tree can used for a canoe. The master builder or the master carver would go and look at the trees in the forest and identify one. And there will be a series of rituals and ceremonies that would be performed before you could actually cut down the tree. "And all of that ceremony and all of that ritual is a way of appeasing, amending, asking permission for the spirits to change the form of this tree to another form, to another useful form for the community. Same with fish, same with the ocean, the wind, the taro patches.”

|

|

|

“There are certain forests where you don't go,” Kathy says. “It's part of a community. When I grew up in the village, we had an area where my grandfather said, 'don't go there, it's sacred.' And it had a huge tree with nuts on it. And that patch of forest was old, it was thick. It had a lot of brush and all that, and we weren't allowed to go there. And I said ‘why not?’ ‘The spirits live there.’ And that's just my small village where I grew up. I'm sure they're all over Palau like that—areas where you're not allowed to go.” “Every village in Palau is like that, “ Walter agrees. “Where they used to pray, to their own family gods or village gods, clans gods or whatever individual clans and such. In the forests, there were various areas where the spirits were supposed to dwell. They could be from water, or land, or be flying kind of creatures too. This was true in the olden days, but not there now. After Western contact, people came over here and they sort of dissuaded them. "But they even have a place where they could go and if they want, they can do magic powers to kill an enemy if they didn't like him. And those are sacred too: you cannot just go over there, or the evil thing might get on you and you get sick.”

|

|

|

|

|

“There are areas where you have to know at what angle you should approach them,” Kathy says. “There is that knowledge, but that knowledge is privileged knowledge. Only a certain clan, only certain people have it, it's not general knowledge that the public knows. It's relegated to a particular group of people only. So that's the kind of information we have in Palau. It's not out there so you can go and search it, but it's privileged.”

|

||

|

|

||

“The hunters go all over the forest,” Tarita says. “Traditionally they hunted all kinds of birds, pigeons and fruit bats mostly. But traditionally there were lot of other birds that were eaten as well, like the starlings. And still today some people eat the starlings. There are two species of pigeons, and the fruit bats were the main targets.” “When I was growing up, we went hunting,” Noah recounts. “We hunted pigs and pigeons. So we learned the trees and the names of the seasons and the parts of the forest from a hunter's perspective. “It's a fun thing. In the old days, they camped out on the hill and they raised pigeons to help them with hunting. You know the season for the way the pigeons are feeding on certain trees and in certain forests where you should be so you kind of follow that. "The old type of hunting was where they would go and build a hut and they would carry their pigeons. These are pigeons they would raise so they would be tame pigeons, pet pigeons that they would take to the hills with them."

|

|

|

“There they would build a small hut and they’d set up the tree, the branch that the pigeons would be feeding on, and they would put the tame pigeons there. Then they'd stay in the huts and would be calling the pigeons. And they would use blow guns and bow and arrow to hunt them. I didn't see that, but my father saw people, elders who actually practiced that, but not when they were young. “But in my time, basically you go with guns and you go out early in the morning and you come back in the evening, and you hunt. So when I was growing up, we learned to call pigeons, and to know where they are and their behavior, and we trapped them and we got them. And pigs—we chased the pigs with dogs and we got them, brought them home, and ate them."

|

|

|

|

|

“There are no formal rituals for going into the forest, except for canoe builders and house builders. They would do that. There is a way of getting the trees which will follow protocols; ways of using the trees, ways of using the logs, ways of building the house, ways of carving the canoe, ways of launching it. I saw that practice. Otherwise, with the forest, pretty much you get permission. The only thing that I know is that if you want something from the forest you have to get permission. It's not a free-for-all, where you just go and do whatever you want to the forest. I think that's the main difference between then and now."

|

||

|

|

||

"There is a process of getting a permit in Palauan way, oltúrk, which really meaning 'going to the source.' Oltúrk means go to the end, wherever the end may be, to get that permission. So when you cut a tree and somebody asks you why you cut that tree, you may say, 'oh I went to the end' meaning you went to the source to get the permission, wherever that may be. "That person may be the chief, may be the head of the clan, or maybe the person living nearest to a particular tree that you wanted, the place where you're getting certain things. or it maybe all the way to somebody else—the owner. But you go to the source, whoever it is—the ultimate authority. You went to the ultimate authority."

|

|

|

"The alternative is you ‘inform’: maybe there is no ultimate authority. Maybe it cannot be found. Then you simply have a formal telling: tell someone formally, and that means the nearest guy closer to the source or closer to the tree, who's most likely to know what's going on. "Then you might go and say 'okay, see what I've done. I've looked for people from whom I could get permission. I can't find anyone. I want to get this forest product because I need it, but I want you to know that if anyone wants to know, it's me, this is my name, I got it for what and I'm aware." So that's informing. But that's all kind of changing. " I think the difference now is that people think that they own the forest, that they can go and take whatever they want. So the attitude has changed."

|

|

|

|

"The old attitude was, the forest doesn't belong to you. You get a permission to get something, whereas now the attitude is, forest is public: unless there's a law, you can do anything you want. It's the same way with our reefs. I think our way, our system, is that everything is closed until you get a permission. If you know no one owns it, then you tell, you inform someone. The Western way seems to be, everything is open unless there's a restriction. So that's sort of some confusion." “That's why people are losing respect—because they don't ask permission. They just want to go and cut the tree without asking anyone."

|

||

|

|

||

Bringing logs out of the forest, as Tarita will explain, was often done down the streams that bring water to Airai.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Airai Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||