|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

“A village is always around the stream, the river,” Kathy says. “The lower part is for bathing. The further up the stream is for drinking water, then further up is protected. Nothing goes in there. So after you work, you go to this bathing spot, where there is bathing for men and bathing for women."

|

||

|

|

||

"Usually there are separate bathing areas for men and women. In the village where I grew up, there’s just this one bathing spot, and so men would go bathe first, then women go bathe second. Then we kids, we’d go after, because we’d go and mess around the whole place and make it dirty. “We would go up there about five o’clock, and we kids would go in at around six o’clock, just about dusk. Everybody else will have taken care of themselves, and then when we’re in there, we would have water fights or swim everywhere, churn up the water and make it murky. The next morning, the same thing. "But we know, we took care not to go to the next level up, because that’s where we get the drinking water, and then further up is completely taboo. Nothing goes in there, because that’s the source."

|

|

|

“Traditionally, you’re not supposed to bath upstream,” Tarita says. “You’re supposed to bath closer downstream. And even for swimming and things like that, it wasn’t good practice for people to swim upstream. Kids especially would know, when you’re walking around up in the forest, you’re not supposed to go swimming up in the streams, because the water flows down and of course it’s the drinking supply and all of that. “I think not every village had a bath, but many of them did, and some of them were not streams but were like springs, they would line the sides of the spring to make it deep. There are some that do fall alongside a river, but not all of them. I think in a lot of cases, in the different villages, people would just bathe in the rivers, but again, as far downstream as possible so as not to affect other peoples’ water.”

|

| |

|

|

“There are five major watersheds on Babeldaob, and Ngerikiil is one of the major five, and that’s the one in Airai State. Mostly on Babeldaob the streams are permanent. We do have some that are intermittent, seasonal, but most of them are permanent, I believe. And there are a lot: we have like 500 million gallons a day. So we have a very good, healthy water system right now. “Palauans mostly did their logging alongside of the streams, and then they would plant—because it was easier for them to get timber out and down to the village if it was alongside the streams. So a lot of their timber species were planted alongside streams, and they would harvest there as well. Can you imagine? It would be really difficult to pull a big huge tree out of the deep forests.”

|

||

|

|

||

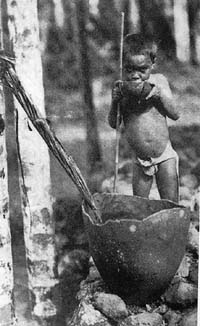

“For cooking and for other things, washing plates and so forth, we get water from the stream,” Kathy continues. “But we caught our drinking water from the rain. Palauans knew the art of pottery. Our ancestors brought it, so we knew how to make pottery. We didn’t have drums and big containers like today, but we had containers for most of our drinking water. “There were big clay pots, clay jars, and what they did was put it under a betel nut tree. The coconut tree has a sheathe that covers the flower stalk, and they would put that sheathe there. It catches the rainwater. Later on we had a big cauldron, I don’t know where it came from, that’s beside this big tree with this sort of a funnel, and we just get a different, catch, to take the water."

|

|

|

“There was a little bit of fishing in streams” Noah says, “but mainly Palauans don’t really like freshwater fish, so there’s really not much fishing going on except some people may like to eat freshwater eels. Shrimps are only taken when they’re clearing the water, the streams. They get the shrimps. Other than that streams are very much treated as a way to get it for the people or trail to go to their properties. “Some people used to eat some of the freshwater fish species,” Tarita adds. “There’s a freshwater eel, it’s called kitelel, and the longest one recorded was about 3.7 feet, but it’s one of the species that certain villages ate, and certain villages did not. It’s actually a totem for different clans in different villages. They weren’t eaten commonly. I think it’s one of those last-resort kinds of foods, like if the weather was bad and people couldn’t go out fishing, then they would resort to something like that."

|

|

|

|

|

“Nowadays we definitely have environmental issues with our streams. The Palau Conservation Society actually is working in Airai, working to help them develop some kind of management plan for their watershed. They have a lot of development going on in the upper parts of the watershed, and I think that’s the reason for the brown water: the sediment is getting into the stream. A lot of people were thinking that might be related to the road. It’s possible, but I think most of it is from development that’s occurring in the upper reaches of the watershed, and there’s not a lot of control for the sediment.” “The streams are not owned,” Noah points out. “It’s communal property for Palauans, and the biggest use of the streams is for mainly taro patches and for bathing. Also for the water trails and navigation. But streams are mainly communal property, where the use was to feed water to all the taro patches. "So for the main stream, no one would block it, and every now and then they’ll gather people to clear the streams to allow the water to run through. That’s a community project.”

|

||

|

|

||

The close relationship of water to food leads us to look at planting in Airai.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Airai Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||