|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Most of the missionary activity happened in Guam,” Noel says. The arrival of Father San Vitores in 1668, and his subsequent death at the hands of angry Chamorros set in motion the military conquest of the Mariana Islands. This story is recounted in detail on the GUAM website. Here, we learn about the effects of these events upon the Northern Mariana Islands:

|

||

|

|

||

“I think the Europeans exaggerated too much how bad it was here,” Noel remarks. “There’s an article I read that we had blankets, we had pillows, we had curtains, we had this and that. I mean, come on, Spanish, don’t make us look so bad! The Spanish ill-treated the locals here. "Father San Vitores, for example, requested a lot of flour so

he could make biscuits and cookies to attract the kids with the smell,

so he could baptize them. He really liked to request a lot of gunpowder,

muskets and bullets, too. There’s a priest doing that.”

|

|

|

“We now know that from the priests’ point of view—the priests that later stayed here—that they found that, ‘Wait a minute, these people are not barbarians; we the Spanish are barbarians. We came here to slaughter them and these are very peaceful, loving people.’ This was seen in how the Chamorros settled disputes. "There’s one account where a man killed somebody and then they sent him to another village, another island. And then the parents of the man who committed the murder went to the family and asked for forgiveness, and they accepted, and they brought turtle shells and they told the man to come and they forgave him. Things like that."

|

| “After this sporadic war, village to village, people were surrendering,” Noel adds, “because the Spanish wanted to congregate all of them into one area. And in order to reduce the force, their warriors and soldiers, is to kill the warriors as much as possible and burn the canoes. So they did burn a lot of the canoes. "The last war, the very short war, was on Aguigan island, which is next to Tinian. And then they took all of them, with the help of a lot of Chamorros from Guam that were allied to the Spanish, and they used canoes to transport all of them. So everybody was moved out of here to Guam, except for those on Rota or a few bandits that just hid in caves."

|

|

|

|

|

|

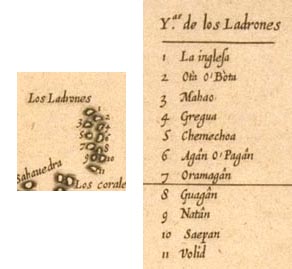

“In the 1690s, the Spanish came up,” Scott says, “and they conquered Tinian and they conquered Saipan, and they went up to the northern islands. There was a little bit of resistance up there. They ordered all the people down to Saipan and they integrated them into those two mission villages here. "We’re not exactly sure of the exact date, but somewhere in the late 1730s or maybe around 1740, there were two mission villages established here on Saipan. We think one was about where Garapan is now, and the other one was down about where Chalan Kanoa or Susupe is."

|

||

|

|

||

"The traditional settlements were abandoned and people were required to move into those mission villages, which lasted for about 30 years. And then we don’t know the exact circumstances but I guess the population got low enough that the Spanish thought that it would be good to bring them to Guam. “At some point maybe 400 or 500 of them left one night and went back up to the Gani islands. The priest was all upset and he got in touch with the governor in Guam and they decided they were going to launch this big expedition up there once and for all, and they went up with all kinds of canoes and a frigate and several hundred people, and there was no fighting. They got the people and took them straight to Guam."

|

|

|

“The Spanish never got around to getting everybody off Rota, so it’s been an isolated little enclave since ancient times. Rota was much closer to Guam. It was a lot easier to get to and it has slightly different history. They were never really violent to the Spanish. The Spanish that were killed on Rota were normally killed by troublesome people from Guam or Saipan. "The Rotanese seemed to be a very peaceful people that didn’t really mess with anybody. But during the Spanish-Chamorro conflict, you had Chamorros that were either wanted by the Spanish for capital crimes or who just got tired of dealing with the Spanish, and wanted to live their own lifestyle. They were going up to Rota."

|

“Governor Jose de Quiroga didn’t like the fact that they were up there doing their thing, and so he launched a number of expeditions up to Rota. They could reach Rota fairly easily, but they had a hard time when they tried to come up to Saipan and Tinian. It is a much longer trip, and they were always running into adverse weather. "So they had a number of expeditions where they were going to come up to these islands and they would get to Rota and then the weather would be bad and something would happen and they would spend some time on Rota and then they would turn around and go back.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

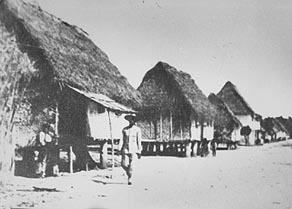

“In the 19th century, the main Spanish presence was on Guam.” By this time, as explained in the Arrival chapter, Carolinians from the islands of what are now Yap and Chuuk had arrived in Saipan and Tinian, and settled there with the permission of the Spanish Governor on Guam. “The Spanish would have had an alcalde here,” Scott continues, “and they would have had a priest or two. That would have been the main church in Garapan, and there was a church in Tanapag so there would have been a resident priest there and that was pretty much all that they needed. The affairs of the island were pretty much run by the priests."

|

||

|

|

||

| “All the major transformation of Chamorro culture happened well before the Chamorros moved back to Saipan. Most of the Chamorros that came back would have returned in the 1850s, 1860s, 1870s. They didn’t become the majority population here until just around the turn of the century—the Carolinians actually outnumbered them. And the Chamorros had been Hispanicized while on Guam. "Once they got up here, you had the priests looking out after you and you had to pay your tax or whatever, but that was probably pretty much it. Spanish really didn’t have much way of asserting themselves directly. They had a hard time getting up here, and it was a big event when they did."

|

|

|

“One of the Spanish governors visited Saipan, I think in 1855—perhaps it was de la Corte. There was no priest at the time, the church was dilapidated, and he was all upset. The people weren’t getting married properly and they were ‘living in sin’ and these things, and so he went back. "But when he arrived, they had a big welcoming dance on the beach. I mean this was a big deal. ‘Our governor from Guam is here. We haven’t seen him in ten years or so.’ "These were really distant outposts at the time. Guam was an outpost itself, but these were like the outposts of the outpost.”

|

|

|

|

While Guam had been a Spanish colony during the 18th and 19th centuries, it was not really until the arrival of the Germans in the early 20th century that the Northern Mariana islands were truly transformed into a colony.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tanapag Home | Map Library | Site Map | Pacific Worlds Home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Copyright 2003 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

|||