| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

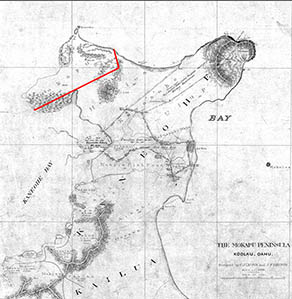

“Kāne‘ohe Bay is surrounded by some of the most well-watered lands in Hawai‘i,” Dennis writes, “and some of the most beautiful mountains in the world: the Ko‘olau Range peaks, two to three thousand feet high, joined by walls of sheer green cliffs. Ka Moa‘e (the East-Northeast trade winds) sweeps warm moist air into the mountains, and clouds form along the summit. Rainwater has cut steep gullies into the cliffs giving them their distinctive wrinkled appearance. When it rains, dozens of thin silvery waterfalls run down the vertical gullies; half obscured by rain and mist, the waterfalls seem to pour directly from the clouds. “The names of ahupua‘a [traditional land divisions] around the bay celebrate the life-giving water that collects in the mountains and flows through the rolling hills and flatlands into the Bay: Waiakāne (“Water of Kāne”), Waiahole (“Water [of the] ahole fish”), Waihe‘e (“Slippery water,” or “Water [of the] octopus”). Water was so highly prized in ancient Hawai‘i, it was synonymous with wealth and life. Such “Wai-lands” were coveted by chiefs and priests; in one version of the story of the pig-god Kamapua‘a, the priest Lonoaohi, who saved Kamapua‘a’s life, asked for all the wai-lands of O‘ahu; and the generous (or foolish) pig-god granted his wish. Kāne‘ohe Bay is named for the ahupua‘a and stream on its southern end: Kāne, the god of water, and ‘ohe, bamboo, one of his kinolau (bodies), which flourishes on the rainy windward sides of the islands.” Within this verdant landscape lies the ahupua‘a of He‘eia. “We found out that it’s a much wider ahupua‘a than we thought,” Mahealani says. “If you travel a long Kahekili Highway, the beginning of the boundary between Kāne‘ohe and He‘eia starts at this ridge above Kāne‘ohe District Park. It comes down and across Kahekili Highway and jumps to the ridge along Kea‘ahala Road. "Then it comes winding down this way and it comes to where American Savings Bank is, and it jumps across the road to Lilipuna hillside. It goes along Lilipuna hillside and it crosses to Coconut Island and it crosses over to Mōkapu where the miliary base is, and where the airfield landing strip is. That is a boundary between Kāne‘ohe and He‘eia, on this side. On that side I have to really study the maps, all different maps. “If you go down to the cemeteries in He‘eia, there’s Temple Valley Shopping Center. I had to go up into the cemetery, up high so I could compare the ridge lines to the map—I have several maps. And it looked like it was a ridge on the Kahalu‘u side that really was the boundary, on the Kahalu‘u side as I’m standing at the cemetery. "So the ridge on the other side of Hui ‘Iwa Street was actually the boundary for He‘eia and Kahalu‘u. Not the first ridge where I was standing. Everybody thought it was the first ridge, so that Temple Valley was all in Kahalu‘u, but apparently part of it’s in He‘eia. So He‘eia is really wide at the top, and the bottom goes over this rolling little foothill down to the waterline. There’s a blinking light as you go along Kamehameha Highway and that seems to be the boundary between He‘eia and Kahalu‘u on the makai end. The fishing pier is in He‘eia.” “Pu‘ukahuauli is the peak behind Keahiakahoe,” Ian says, “Keahiakahoe is where the Ha‘ikū steps are. And then the next peak as you’re going up Likelike side, you see the big giant wires coming down from her breasts. The telephone wires coming over the peak. Pu‘ukahuauli. And that’s the underworld sea goddess. According to missionary William Ellis, it turns out that’s also the patron deity of surfing in Tahiti. Ben Finney records that in his book. That’s the Kāne‘ohe and He‘eia boundary.

"On that side, you can turn around and see Pu‘u Pahu. Where you see the townhouses there with the pine trees and then you follow the hill down to where there’s the low, rolling hill there. That’s Pu‘u Pahu. And then the head of that mo‘o is down there, Pōhākea. You can see when you see the body of the lizard, the dragon the head being down there by the water. That hill runs straight up along the boundary of He‘eia and Kāne‘ohe. “As we stand near the Hina stone at Mōkapu, we are halfway between the Kāne‘ohe and He‘eia ahupua‘a boundary markers. This is in the center of He‘eia, with Kanehikili straight behind in the back of ‘Ioleka‘a; Leleahina on the one side, Kukuiokāne on the other side. The boundary at Kailua-Kāne‘ohe is actually on just this side of Obama’s house in the Gold Sand Beach there. Pu‘u Nao, ‘grooved hill,’ is the actual place where Obama’s house or Castle Point House is.” Traditionally, He‘eia was divided into two parts at Ke‘alohi Point: He‘eia Kea ("white He‘eia," towards Kahalu‘u) and He‘eia Uli ("dark He‘eia," towards Kāne‘ohe). A version of the story of H‘iiaka-i-ka-poli-o-Pele from the Hawaiian newspaper Hoku o Hawai‘i (Jan. 5, 1926) states

Raphaelson (1925) tells of the tradition of He‘eia as a leina, or leaping-off place of souls:

“I belong to the Aha Moku,” Rocky says, referring to an advisory board made up of one representative from each island, “and I’ve been going to these pūwalu [united, cooperative] meetings for years where we’re trying to get first traditional practitioners for the Aha Moku. First of all, to get on the Aha Moku, you have to do your genealogy. A lot of people want to do councils, but for a traditional practitioner, you got to know your own traditions from your own ahupua‘a, your own moku. And then that’s your kuleana to take care of that moku. And a lot of people don’t know where their kuleana starts and ends.

“We go out in the oceans, we do the wahi pana tours. People will tell us, ‘How can you tell where the boundaries are?’ We know. We’re brought up. We’re told this is where the boundary is. So I told Mahelani, ‘We got to make some markers in Ko‘olaupoko.’ We were supposed to do only Ko‘olaupoko.’ “We have eleven ahupua‘a in Ko‘olaupoko, with nine right in Kāne‘ohe Bay. The ahupua‘a go from mauka to makai, mountain to the ocean. We know where the boundaries are, but not everybody knew, so we decided to put ahupua‘a boundary markers up. It took us five years. We had to meet with the federal government, the city, and the state. The federal government wouldn’t let us put our ‘okina’s in the words. The city didn’t want to spend any money, and the state didn’t want to spend any money. “It cost them nothing. We had a private donor that did everything for us, and we dedicated it and gave it to the city, but it took us five years to do it. We had to meet with every Hawaiian Civic Club in Ko‘oalupoko. We had to meet with all the neighborhood boards in Ko‘oalupoko. We had to meet with all the different organizations plus the Department of Transportation from all branches before we could get it done. “And go to the spot and show them where it’s at, and get traditional knowledge from the people from that moku and that ahupua‘a. They are the ones that know best. They know their practices. I cannot go into Waihe‘e and tell you their practice. That’s not my kuleana. But I can tell you everything about He‘eia because that is my kuleana. And if somebody from Waihe‘e is going to come tell me, I can tell them, ‘No way. This is my kuleana. Take care of your own kuleana.’ “Now these signs are island-wide. The Department of Transportation wanted to do it island-wide. And now, the neighbor islands want to do it. They commissioned Mahelani, and she has been going on trips. But I said, ‘I’ll go. I’ll show them everything.’ Just how to go about doing it, and it’s that easy. Because you don’t want anybody to get angry with you, you want to make sure you get the traditional markers.” |

|

|||||||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

|

||||

Copyright 2019 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||