|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

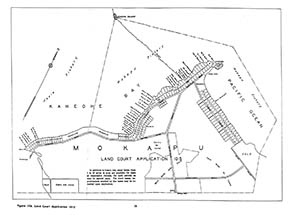

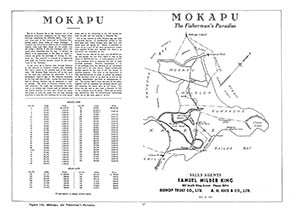

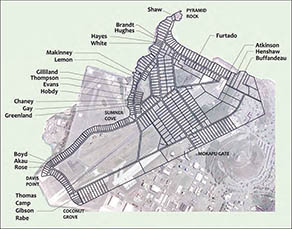

“It was the Rice and King family that put in to subdivide this western side of the peninsula.” June says. “They were selling off lots, and so that’s why you have this community.”

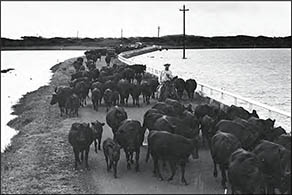

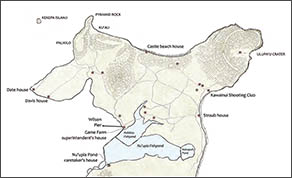

“My grandfather became the gatekeeper at Mōkapu for Kāne‘ohe Ranch,” Chuck says, “that owned large portions of the property of Mōkapu. Our home was situated just below Ulupa‘u Crater, where Fort Hase Beach is now located [on the Kāne‘ohe side]. The military would pass b to go up to the firing range. I remember my grandfather going over and visiting other relatives the other side of the Ulupa‘u crater, where there were residential homes. “I remember the Army trucks passing by our place, I guess they were going up to the site where the present firing grounds are located, to practice their firing at that site. But they would stop at our place and toss out a sack of saloon pilot crackers which was a welcome part of our meals. “And I also remember riding in the rumble seat of my grandfather's Chevy when he drove to the other side of Mōkapu, where they still had family members and other residents living before they had to give up their property to the military and leave. At that site was my first remembrance of the larger Mōkapu.” Then, with WWII knocking on the door of the United States, the base was reactivated as Fort Kuwa‘a‘ohe. It was renamed Fort Hase in 1940, in honor of Major General William F. Hase, who served as Chief of Staff of the Army‘s Hawaiian Department from April 1934 to January 1935. The base served as the headquarters of of Kāne‘ohe Bay’s Harbor Defenses. “The army took over Mōkapu in the early 1900s,” Mahealani says, “and they started building the base. They dredged the bay. That affected the waters of He‘eia as well and it damaged a lot of coral. They used explosives to break up the coral so that they would have easier thoroughfares for their boats to land and load and unload. "So they did a lot of damage to the bay. They did damage to the coral beds and they had like clams and other shellfish beds along the shoreline, more in the Kāne‘ohe side, the south end of the bay. But that was all polluted by the work that the military did to build the base.” Naval Air Station Kaneohe was established on the ‘ili of Mōkapu in 1939 to develop a base for seaplanes in support of the Pearl Harbor fleet. The work included dredge-and-fill operations, adding 280 acres to the ‘ili, and filled low-lying areas for runway and hangar construction. “They were getting ready for the war,” June points out. “They were preparing the landing mat over here, which was the early runway for the Navy sea planes. It was probably 1940. In 1939, they started coming out here, the Navy acquired it and started building the hangers and the original runway. “Mōkapu at that time, besides portions of it belonging to Kāne‘ohe Ranch, also became under the control of the Navy,” Chuck recalls. “That’s when the Navy first started to establish their airbase, particularly for their PBYs—the flying boats that took off from there—before it became under the Marines. “There’s a lot of history to the development of Mōkapu into the base, displacing the ranchers who ahd brought their cattle, as well as Japanese farmers who rented or leased the areas around the crater for the growign of their vegetable crops."

“In 1940, the Navy began acquiring more land on the peninsula,” write Tomonari-Tuggle and Arakaki in their booklet Mōkapu: A Paradise on the Peninsula. Stories From Not So Long Ago (2014), “ultimately condemning the privately held lots in the Mokapu Tract Subdivision. The residents of the western peninsula were given notice that they had three months to surrender their homes. "Many of them were just beginning to move into permanent homes that they had spent the previous five years building....Some of the houses were reused for temporary Navy housing until permanent facilities were constructed, and others were bulldozed for the airfield.” Henry Thompson, whose family used to visit uncle Jimmy Lemon at his house on Pali Kilo, is quoted in this booklet (p. 46) as saying in 1981, “They didn’t have much choice. There was no such thing as to protest the military taking this area of land. We just accepted it...the government was very powerful then. And when the time came you picked up and moved...personal belongings were removed from the property. I remember because I had to help my uncle load up the truck.”

“My father was raised on Mōkapu,” Emalia says, “because my dad’s uncle owned the peninsula until 1930; then it got condemned for a base. All the fishing areas my brothers know about and my dad used to tell them where they could go, where they couldn’t go. I mean they’ve dug up a lot of our bay and fishing places. They’ve covered over fishing spots, and they say it’s for security. “Then bringing us forward, the ‘ohana, the family, we are claimants to all the ‘iwi (ancestral remains) that were discovered there in the 50s. So there’s over 1,500 sets of ‘iwi that we need to put back there that the military dug up.”

“I think that military wasn’t here, it may have been different,” June remarks. "If those houses that were here in the 1930s, if the federal government didn’t take over, that could’ve continued development. And you’d have another Kahala or Diamond Head out here.”

|

|

|

The Naval Air Station was still fairly new when it would see sudden, unexpected action. Japanese bombing on December 7, 1941 brought He‘eia into Wartime.

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

|

||||

Copyright 2019 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||