|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| People | Environment | Losing Land | Development | Sovereignty | Language | Sources & Links | |||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

“Our family has been involved a lot with the He‘eia,” Rocky says, “even growing up, the fish pond. I’m glad that Hi‘ilei them are at the fish pond. Because from the ‘50s to the ‘80s, we fought to save this land. We went bankrupt. Married to my husband and I went bankrupt three times in my life. If I had to do it over again, I’d do it.

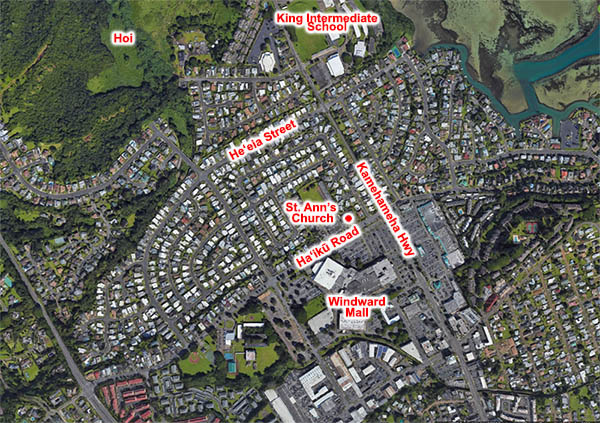

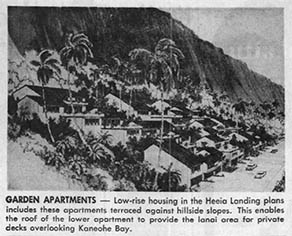

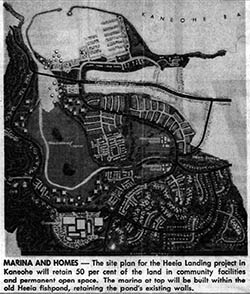

“We fought against the nuclear power plant being built in He‘eia Kea. They were going to build it. They evicted all of our people. We fought them for ten years. We went bankrupt. We were the first community in the history of the state of Hawai‘i to fight a public utility right up to the Supreme Court and win because of that nuclear power plant. If I had to do it again, I’d do it." Bishop Estate had already turned two of O‘ahu’s fishponds into suburbs with private marinas. Ka‘elepulu Fishpond in Kailua became “Enchanted Lakes,” Kuapā Fishpond bnecame Koko Kai Marina in Hawai‘i Kai. The Estate sold the development rights for He‘eia to Gentry-McCormack to turn the fishpond into a residential marina. By 1964 the City Planning Department had approved a plan to build homes inside the pond and a golf course in the traditional taro grounds upstream. In 1972, seven years after the 1965 flood had blown a hole in the pond’s retaining wall, temporarily ending the pond’s function, Bishop Estate tried again. As reported in the Honolulu Advertiser, August 3, 1972:

Fortunately the pond was placed on the U.S. Department of the Interior’s National Register of Historic Places in January 1973, ending that plan. By 1974 the pond was re-zoned from Urban to Conservation District and earmarked by the State Legislature with $4 million to be turned into a State Park. In 1976 the developer proposed to construct 5,020 houses in the wetlands and use the pond a settling basin and sediment trap as part of its suburb’s drainage system. Finally in 1976 the State legislature re-zoned Hoi to Conservation and asked DLNR to explore condemnation, setting in motion a process for the State to acquire the pond, Ke‘alohi Point and Hoi wetland. Eventually the State would buy the Ke‘alohi point over the fishpond, put the state park there, and then run out of money. Bishop Estate kept the wetland and the pond. “It started in ‘75. The fish pond," Rocky continues. "I almost went to jail for the fish pond. They were on it to build, I saw the plans that they had. They made this big, plastic model. They were going to make a drawbridge where the long bridge is, and the fish pond was going to have this 500-birth marina.

“Where our lo‘i is, it’s going to have a hotel and another Hawai‘i Kai. We fought that. In fact, we held the city and county, the planners, we held them captive in the office overnight. We didn’t let them go in the elevators until they listened to us. They would not listen to us. “Mauka of the fish pond is what used to be called He‘eia Meadows in modern times,” Mahealani adds. “It was all taro fields before. And then in the time since the Japanese immigrants came, it became rice fields. ‘He‘eia Meadows’ was a fancy name for the place they wanted to develop. And the community wanted to fight that development and we were able to prevail. Then under Governor Waihe‘e, he traded that property—that whole marshland above He‘eia fishpond—with Bishop Estate for some land in Kewalo Basin where Bishop Estate is now building highrises. "And so that land was protected, and now Hawai‘i Community Development Authority manages it and has leased it to our another partner organization called Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi, which is in the process of restoring the 400 acres to food productivity.” “My husband worked for the construction company,” Rocky recalls. “They built up the dirt, so a lot of that is land filled. My husband helped to make the mound until he came across the biggest tree he saw. He was supposed to bulldoze it. He refused and he got fired. And he came home and he told me he got fired. He said, ‘I couldn’t operate it.’ And I said ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Well, they wanted me to bulldoze that tree.’ I said, ‘Thank you.’ But the next guy bulldozed it anyway. But the purpose was, he didn’t have it in his heart to do that. That’s something to us. A big tree like that takes over 100 years to grow.”

“We fought against this mall,” Rocky states. “We said that this mall will bring a lot of change to our people. It’s a cultural change. There would’ve been more people, which it brought more people. They wanted to get rid of our graveyards, which we fought against that for years—that’s the only thing that saved our graveyard. But if you look at it now, it’s something unique in the middle of a shopping center.

“Kamehameha Schools didn’t own all of it. People think Kamehameha Schools owned that property. My family owned part of that property. They had kuleana landowners. They never sold it. Maybe about 20 years ago, they sold that—that’s how old the mall is. They refused to sell it. They leased it out, until finally a lot of them died, other cousins got older and said, ‘Let’s just sell it’ because of taxes and all that. And so, a lot of the kuleana people had to move. There’s a lot of old families in there. You had kalo patches and that had to move. “The guy that owned this building owned part of the mall too. He owned the only grocery store at one time, the only market. He let our people charge, and they couldn’t pay a bill, ‘Well, give me some of your property.’ So he got a lot of property. He owns this building. He’s in his 90s now. “That was in the ‘60s and ‘70s, the planning of the mall. We were labelled activists, radical activists. You know what? I changed our name today. I told Mahealani, ‘We’re advocates for the ‘āina, to sustain what we’ve got left.’ We’ve got a lot to sustain, starting with the fish ponds.”

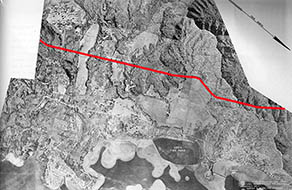

“When I was a kid,” Mahealani says, “I went to school through the old Pali Road. There were no tunnels at all. Old Pali Road was a winding road up the mountain and that was how I went to it from school every day. So I’m carsick because I’m reading while I’m riding, it makes you carsick. And then the bigger change was when they built the two Pali and Wilson tunnel, major changes. Wilson tunnel, when they built it they damaged a burial cave and intercepted some major dike water sources, water compartments, and six people died drowned in a flood from one of those dyke compartments and people feel it’s because they damaged the burial cave. That’s Wilson tunnel; Pali wouldn’t have too many incidents.” “Wilson tunnel, was the one that killed quite a few people, died,” Alice recalls, “and it kind of caved in somewhere. I was in Kaua‘i playing baseball when it came on the radio that there was happening, so a lot of the families from Kailua was in that.” “Before H-3,” Mahealani continues, “while they were building the Wilson tunnel, they were planning Kahekili Highway as an alternative to Kamehameha Highway. Kahekili highway would open up the whole windward coast. "And around the ‘70s or even the ‘60s people were really having anxiety about what would happen with all these roadways opening up more land. Especially the farmers and some who cared about the environment and the water resources. They banded together in 1977, the community really fought against any major developments beyond Kāne‘ohe so that He‘eia on would all be kept for conservation, water resources and farming. Read about protesting the construction of H-3 Lilikalā talks about upland imu found during the construction

“H-3 is used by workers who work on the opposite side of the mountains, people working this side from there could come this way. But it was really a make-work, truly it was, because Dan Inouye was trying to make his mark, bring home some pork barrel for Hawai‘i and that was his biggest pork. “When the proposed H-3 was in the early review stages, they had a study called the Eckbo, Dean, Austin and Williams study—they called it EDAW Study—and in that study they said that with the coming of H-3 would bring urbanization of the Windward side. The communities beyond Kāne‘ohe—He‘eia, Kahalu‘u, etc.—they would be exposed to urbanization. And with more urbanization, those older communities where old family still live, the elder people would not be able to afford the increase in property taxes and they would lose their land. So a lot of social problems would happen which is happening. Everything that was predicted by the EDAW study is happening today. So the EDAW study predicted the adverse effects of H-3 on the communities of He‘eia all the way down the coast. “That’s why what you see in this area is a lot of extended families living together. There are a lot of pluses to it, but also a lot of hardship, lack of privacy and things like that. But families living together, ‘it takes a village’ is good. They’re all helping raise children and maybe multi-generation is good for children to be with their grandparents.

“One of the big issues currently is the proposed widening of Kahekili Highway. We are concerned about runoff from the highway getting into the lo‘i and the fishpond: oils or the materials from the cars, the fumes, exhaust, whatever getting into the fishpond and the lo‘i. That’s one of the bigger issues. Also, any more development of conservation or agricultural land or farmland would be a concern: if there’s any more urban development. More pavement is not necessarily good for He‘eia.” “It’s getting overcrowded with a lot of tourist business,” Rocky says. “That is the reason in the ‘80s, we had the Kāne‘ohe Bay master plan to try to control the commercial businesses in Kāne‘ohe Bay. It was getting too much for the bay. The businesses outranked the local fishermen. So having this meeting, this Kāne‘ohe master plan, we also get this agency or organization put together. It’s called the Kāne‘ohe Bay Regional Council. From that, we have right now supposedly only five commercial businesses that has a permit to have their business out in Kāne‘ohe Bay, the big businesses. No one else is supposed to have it. I’m afraid there’s a lot of small businesses sneaking in on their own. Like tour boat kind of businesses.” Rocky talks about protecting natural resources from exploitation

“We’ve held the line ever since,” Mahealani adds, “but we never let our guard down because there’s always people wanting to develop more and more. And if they widen Kahekili Highway, the carrying capacity is expanded so then they can develop more. And then the pressure will be on to widen Kamehameha Highway, which will lead to more development up the coast. "So we’re really worried about that. All that farmland and the watershed land will be lost. And then with climate change beyond Kualoa, that area, that road will be underwater. So they’re going to have to relocate Kamehameha Highway or right raise it. I don’t think they can raise it. I think they have to move it inland. “What we do in Ko‘olaupoko affects them and what happens in Ko‘olauloa affects us, so that’s why we supported them when they fought the big developments up on the North Shore. Because we know what comes with that.”

|

|

|

|

Many of these issues come down to the control of land, much of which Native Hawaiians lost with the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893. Today, these are issues of Hawaiian sovereignty.

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||

|

||||

Copyright 2019 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||