|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

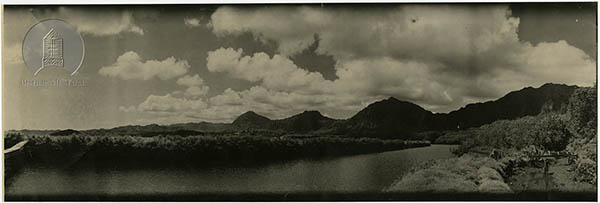

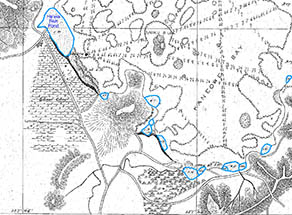

“The whole area was rimmed with fish ponds,” Lilikalā points out, because the water comes from the mountain. So as the water comes into those steep cliffs, it goes down lava tubes and it comes popping up near the ocean. What the ancestors did is they put walls around it, because we don’t have lagoon here like they do in Tahiti. So what a fish pond is, like He‘eia fish pond, is essentially like a freshwater lagoon—mostly freshwater in the olden days. These days, a lot more salt water, not enough water coming down.

“There used to be 114 freshwater fish ponds of O‘ahu. It used to be 3,600 acres before they got filled in. They made 1 million pounds of fish per year just on that land. So we’re talking about food sustainability. I just like to remind all the scientists, ‘Oh, by the way, it’s no big deal, okay?’ So, that’s what the land means to me. That is, to me, the most important stories of this place.” “We had so many fishponds in Kāne‘ohe,” Alice recalls, “a lot right down where the Waikalua road is. Māmalahoa and Nu‘upia, those are the names of some of them. But there’s a lot. There’s a lot. They’re not fishpond anymore because they filled them in. Waikalua was owned all by uncle and he sold it to some Japanese people. And now Herb Lee, he’s with Waikalua fishpond and they’re kind of restoring it. It’s not as hard to restore as was the He‘eia fishpond.” “From what I know, He‘eia fishpond is estimated to have been built between 600 and 800 years ago,” Hi‘ilei says, “and the only way we can get a firmer estimate of a more accurate number would be to do some carbon dating of coral, and I know the technology exists. But it’s between 600 and 800 years ago. The way we see the fishpond today is most likely not the way that it was originally constructed, which I think is a beautiful part of restoring places like this—places of living culture as opposed to places of shelved culture is that it empowers the people to evolve the practice.

“The wall fully encloses an 88-acre brackish water system. The wall goes for 1.3 miles in a full circle that’s about 7,000 linear feet of man-made wall, which I believe is twice the length than any other fishpond found in Hawai‘i because it was built in a full circle. Most of the fishponds you see were just semicircular in construction. So the wall itself is completely encompassing. From what we know, at the turn of the century was irrigated by an ‘auwai that ran the length of the mauka portion of wall. There are still remnants, right here where the kalo is planted, that’s remnant ‘auwai.” Learn about the different types of fish in the pond.

“Over the course of 800 years, this fishpond definitely has gone through many different phases of alteration, no doubt in response to whatever climate phenomena like flooding, tsunamis. As a result there’s also been many folks—families, individuals—that have come to take care of this fishpond. There’s stories of person named Makanui taking care of the fishpond, but the dates are unclear. Another individual by the name of Uhu‘uhu was taking care of this fishpond. “More recently the early 1900s, a Chinese family was taking care of the fishpond. One of the leases on record at Kamehameha Schools was granted to three individuals, and I think two of them were Chinese and one of them was Japanese. That was around 1938 to 1950. And then I think there were probably some people in between that group of three and Mary Brooks, and then there’s our organization, Paepae o He‘eia.” The key characteristics of most Hawaiian fish ponds (loko i‘a) are the enclosing stone walls, and the gates (mākāhā) that allow water to flow in and out. “There’s two materials that build our wall,” Keahi explains.” The pōhaku [rocks] that make our walls, and then we backfill it with coral and that’s that because traditionally, the fish ponds in the bay were usually built like that because the closest resource is the coral. The rock had to come from about two miles away and all in between there and here. The coral came from two feet away. “So instead of building a ten-foot wide wall with pōhaku that needed to be passed for a mile or two, they utilized the resources that were closest to them. And to me they definitely understood that removing the coral wasn’t going to have enough negative effect. Today we don’t touch our coral because our coral that is in the water needs to grow. Today we use an alternative coral that’s been mined inland, and even that’s not the best, but we need to restore this place and we think it’s important. “Depending on its function, each pōhaku has a name,” Hi‘ilei elaborates. “We have our foundational stones which are called niho. Niho are your teeth in your mouth, so they provide that structure, that foundation. Then there’s your alo [face] or what we call kūkulu—those stones that maybe aren’t quite as big as those foundational niho stones, but they allow the wall to be brought up to height. ‘Kūkulu’ which means ‘to bring up to height,’ or alo which means your face. Those rocks that, when you look at the wall, they provide a face to the wall. “And then there’s the pāpale stones. Pāpale in Hawaiian means ‘hat,’ so they’re those stones that are the cap stones. And then if you’re not either of those, you’re an unu, a wedge; or you’re a kihi, a cornerstone; or you’re a hakahaka. Hakahaka are the filler stones. That’s how we talk in terms of rocks. No matter how big or how small you are, you have a role to play in society, and your voice comes from your function. So I always talk about with the kids: it's really important that you figure out your function, what’s your purpose. Hopefully people figure out what their function is sooner rather than later in life.”

“We have four sets of mākāhā that bring in kai—salt water” Keahi points out, “and we have three mākāhā that bring in wai, our fresh water. So we get wai hapa kai, this brackish water environment. And through that combination of salt and freshwater and very nutrient rich fresh water coming down from our lo‘i, it is coming down from our kahawai, this river that’s bringing us life. We’re going to get an abundance of phytoplankton. And then from there you can start to see the little chain reaction. Learn more about the functioning of the mākāhā. “Now we’ve made the smallest form of food possible, so on a dropping tide, that phytoplankton-rich water is leaving the pond. Baby fish are going to taste that and they’re going to come to our recruiting area—our mākāhā—swim through our gates that are just big enough to let the baby fish in, and they’re going to come into our pond and be able to feed on that phytoplankton until they reach another maturity level. And once they reach that next level, the next phase, they're usually too big to get back out. So now the pond stocked up on all on its own. “This pond is fairly shallow, ranging from three to four feet deep. Great depth to promote algae growth, limu growing within the pond, the algae is that these fish love to eat, and now we’ve got free food for our mullet. It took our kūpuna two years and ten thousand people to build this fish pond. And once they built it, it started doing it all on its own: food was here and the phytoplankton was here. It's a great environment, fish are getting bigger and now they reach an age where they want to be harvested. “Three years in, mullet get to a size where we can harvest. They’re going to want to head to the open ocean to start their spawning cycles. There is a little change in how their bodies are now and what they need: they want that more of a salt-water life, but they can't get back out the gates. So they’ll stay and continue to feed in here until the harvesting day. And on the high tide, salt water coming in, they're going to come up to the gates, they’re going to taste that salt water coming through the mākāhā. They’re going to gather.” Learn about harvesting the fish.

“‘Āina momona means different things to different people,” Kelii explains. “Simply, ‘āina means land, or that which feeds us. Momona means fat, fertile, juicy, productive, luscious. So a person can be momona, a land and ocean, a place can be momona. We use that term because there’s a famous quote written about Hawaiian fishponds by Samuel Mānaiakalani Kamakau that says “Fishponds were things that beautified the land. A land with many fishponds was called momona (fat).” “That quote from 150 years ago speaks to the brilliance and the genius of our ancestors in growing fish and growing it in a responsible, sustainable manner. What we strive to achieve in today’s world, well, they achieved it in ancient Hawai‘i. They were able to make estuary systems. Most often estuary systems take advantage of the productivity in estuaries and make the waters enclosed by the ponds more productive than the ocean is naturally. So thereby being able to feed themselves and feed the ocean as well too, so truly making a place better than what it was before. “When land was privatized [in the 1848 Mahele], this fishpond was awarded to Abner Pākī who was the konohiki of this ahupua‘a. But prior to that, there’s no such thing as private land in Hawai‘i. Nobody owned this fishpond and I haven’t read anywhere that this fishpond was set aside exclusively and always for the ali‘i. Some of the books out there tell us that fishponds were for ali‘i and reserved for the ruling class. I have a hard time believing that our 400-plus fishponds in the state were reserved always for a very small percentage of the population. “So I think fishponds were community resources, at least ten months out of the year. Because you couldn’t have gotten people to buy in to building that many fishponds this large if they weren’t going to partake. They must have received some benefit from it. From what I know about Hawaiian society, the maka‘āinana were the ones that held up the entire society, because those are the ones who produced the food for the society. The ali‘i, they’re descended from the gods and they had their place and they had the kapu placed over them and they could tell you if you’re going to live or die. But the common class had the ability to overthrow. They had the ability to kick the ali‘i out. They had the ability to move. It was a top-down society, but if they didn’t like the way their land was being managed, they could dig out or they could kick somebody out. “We have 12 employees, so when you think of producing 44,000 pounds of fish a year and what would it have taken, what would have been involved in the old days to manage this place, I think it would have taken more than 12 people. I truly believe that once this fishpond was built—historical estimates say 2 to 3 years to build the walls necessary and get the fishpond up and functioning—that it may not have taken more than a few families to operate the fishpond.” “So I don’t it would have taken a whole hoard of people to maintain once it was built and then some sort of community sharing process was enacted and they had rolling and then you know that ali‘i comes through, “Okay, everybody take a break.” You got it and then you want to show off the bounty of your fishpond to the ali‘i, and share.”’ Read about some of the Guardians of the Fishpond |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

||||

Copyright 2019 Pacific Worlds & Associates • Usage Policy • Webmaster |

||||