|

Mōkapu Mōkapu |

|

"Aerial Survey of

Mōkapu Penninsula for

Kāne‘ohe Naval Air Station, 1939.

Record group #71, Bureau of Yards and Docks. Photo #111821-e-20."

“Mōkapu is important in the Hawaiian heritage for the fact that it was a favored residence of certain ali‘i,” Kalani says. “Mōkapu is a contraction of moku kapu, meaning ‘sacred island.’ It was at one time an island. And then it was joined to the main island because six fish intervening fish ponds were installed with modern causeways, and they built up over time, the sand accumulates. So now it’s a peninsula."

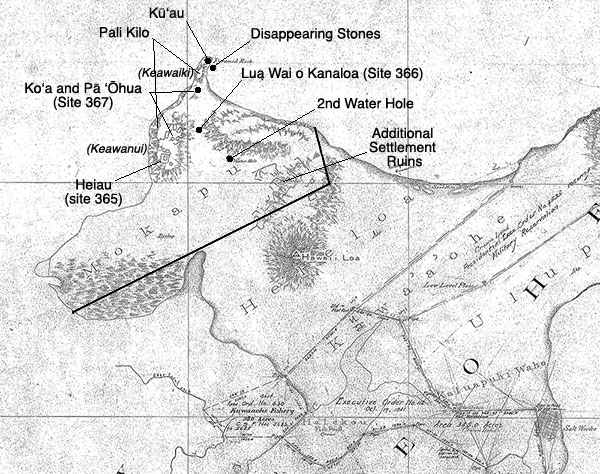

Portion of an 1882 map by Geo. Ed. Gresley Jackson shows the extensive fish ponds that nearly cut off the end of the penninsula.

“Geologically, Mōkapu was a separate island when the Ulupa‘u Crater came into being 500,000 years ago or more,” Chuck explains. “Ulupa‘u is an ash cone or a tuff cone. It’s part of the secondary volcanic eruptions. The eruptions that occurred here were also in line with the rift that goes over the Ko‘olau Mountains to Salt Lake. Salt Lake was formed about the same time as Ulupa‘u Crater was formed. There was a waterway that went across. So when the Hawaiians came, they converted the waterways into the Nu‘upia fish ponds."

"But it was regarded as a sacred place," Kalani adds, "because of the associations with deities like Kāne and Kanaloa, Now, this might be Biblically influenced, but a story says these two gods Kāne and Kanaloa were there at Mōkapu and what they did was to take two kinds of contrasting sands, to fashion the first man. Sounds familiar? I think that’s a Christian influence. That’s a story from Kamakau, the historian.”

“Mōkapu has a spot on the eastern side at Mololani,” Lilikalā adds, “where it is said that Kāne and the akua Kū and Lono helped Kāne to make the first man. And then they make the first woman, which is a different story from Haumea and Wākea, earth mother’s sleeping with sky father, and then having a genealogy that has the first man. That’s a different story, because this one is Kāne doing it, not Wākea.

“Now in that story, they also say how they make a woman for this first man. So, my granddaughter here, she says, ‘Kāne did not make woman! Haumea made woman. Who is telling this story? The story is wrong!’ Of course, that’s because she’s raised here in He‘eia.”

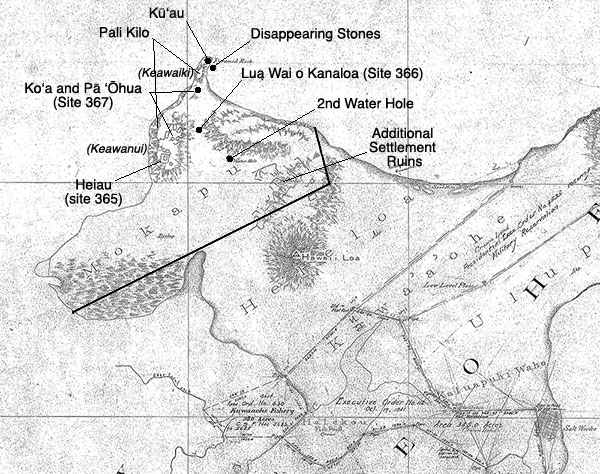

Annotated GoogleMaps image of the end of the Mōkapu penninsula, 2019.

Dennis writes, “Kamakau presents a genealogy in which Papa and Wākea, born at Waolani, in Nu‘uanu, O‘ahu, appear twenty-seven generations after the first man, Kānehulihonua [“Man made from earth”], and the first woman, Keakahulilani [“Shadow changed by heaven”]. These two ‘progenitors of the people of Hawai‘i and of all those who dwell in the islands of the Pacific’ were created by Kāne, Lono, and Kū, the main Gods of the Hawaiian pantheon at the time of European contact.

“The three Gods made ‘a model of the lands of the earth’ in Kāne‘ohe Bay between Kualoa and Kāne‘ohe; when they saw there was no chief to rule over all things, they drew a man in the red-black soil ‘on the eastern flank of Mololani (a rise near Heleloa Beach on Mōkapu Peninsula), facing the sunrise and near the seashore’; then they chanted the figure to life: “Hiki au; e ola!” (“I have come; live!”). The first woman was created from the shadow of the first man. Kamakau’s localized creation story contains both Polynesian and Biblical elements.)”

The protected area with the historic site remains. The sign states "No Entry, Federally Protected Historic Property."

“There’s archaeological deposits in this area here,” June points into the protected area. “They are like remnants of habitation site, but it’s also recorded that in the mid-1800s, there was a catholic church that was built on the peninsula. It could be that part of these. They say that it was dismantled at one point and the rocks were paddled over to the main island and used at St. Ann’s. But regardless of that, prior to that, this was an area where Hawaiians were living and probably coming out here, going fishing, and getting he‘e, salt, all that kind of stuff."

“There was the whole village living on Mōkapu,” Mahealani points out, “and there was a church called St. Catherine’s, made out of coral stone. And when the families were all forced to leave, they also had to relocate the church. So they cut the coral stones into blocks, moved them over here to He‘eia to Ha‘ikū Road and some of that coral stone was used to build the first St. Ann’s Church. There’s one little piece of it left that is found inside St. Ann’s Cemetery right over here so a cemetery right over there. So that’s another story is that St. Catherine’s Church was relocated and the St. Ann’s Church no longer has any of that coral but one piece of coral is still in cemetery somewhere.”

Keawanui, one of the hills on the western shore of the ‘ili.

“Over on the Kailua Bay side," June continues, "there is remnants of habitation over there. We conjecture, based on doing studies of when you are excavating, you’re gathering, you’re screening through the soil and you’re gathering all the food remains, the midden. And you do studies, you weigh them to see, what’s the weight of the pipipi shells that were found? What’s the weight of the wana spines that you find? And from that, you can conjecture how many people were living here at any one time."

“They did a lot of their salt panning out there at Mōkapu,” Emalia says. “My father was raised on Mōkapu because my dad’s uncle owned the peninsula until 1930.”

“They’ve conjectured there were between 100 to 150 people at any one time," June states, "something like that. I think this peninsula was very used. And with the fish ponds, the fish ponds were heavily used. We know that. That’s an important food source, so that was out here too. But I do think that the peninsula, because it didn’t have a good freshwater source, that’s why you didn’t have larger villages out here. But there were some, definitely.

Portion of W.A. Wall's 1899 map clearly shows the location of a water hole.

“Early maps, early surveyors who were here in the late 1800s, they do show on their maps one or two water holes, lua wai, in the He‘eia side. That’s where the maps show it. We’ve never been able to relocate it after that. But there’s been a lot of modern earth-moving out here. We think that they were covered up. But I do think freshwater was scarce out here. I think that also is why you don’t have big, large remnants of large villages or stuff out here.”

“I do think the main island where the fresh water source is, that was where the larger populations were. I think families would come out here to the peninsula for the resources, and they would camp. Because where we find remnants of those sites is along the coastline, both Kailua side and Kāne‘ohe side. And there was an inlet down in the south part of the peninsula, probably right along where the boundary is. I guess maybe a little bit on the He‘eia side, but there was an inlet there. You had a wetland area. You had some higher dunes. So, it was an area that was easy to come and camp. And then there’s a lot of marine resources there to gather.

“I think wells were in use at that time. We just haven’t been able to relocate them. So, I think there were probably at least a couple of freshwater sources. It would’ve been brackish probably, but we haven’t been able to relocate them in the years since.”

Interactive map of sites on Mōkapu. Click on names to read more.

“As a very young child—maybe about 3-4 years old or so—I remembered living there'" Chuck recalls of his family home on the Kāne‘ohe side. "They used to bring their cattle from Kāne‘ohe, Kailua, to Mōkapu. And also in Mōkapu, there were other farmers who farmed the area, raising vegetables crops etc. And that’s where we lived off and on. In the early days, I remember my grandfather getting the kukui nuts, roasting it and so forth, and making inamona from that.

“It was quiet, and the sunrise would come up at that particular time, and family would then get up early in the morning to see the sunrise, also laying fishnets in the ocean water. I remember going with my grandfather as he took his fishing pole to cast into the waters at that particular time. Then also members of our families would come over and visit us at that particular site. It was not a very large home. You entered the kitchen area, and there was a big parlor-type of a living room with a couple of bedrooms on the side where family members would just spread out and sleep there.”

“We didn’t go out to the folks on Mōkapu Peninsula,” Alice recalls. “Not really, not really. We’re kind of disconnected. That and then you get Coconut Island between... yeah and then us on this side. Well, as far as Coconut Island is as far as I could. And once the Marines got there, it became too hard to get in.”

|

|